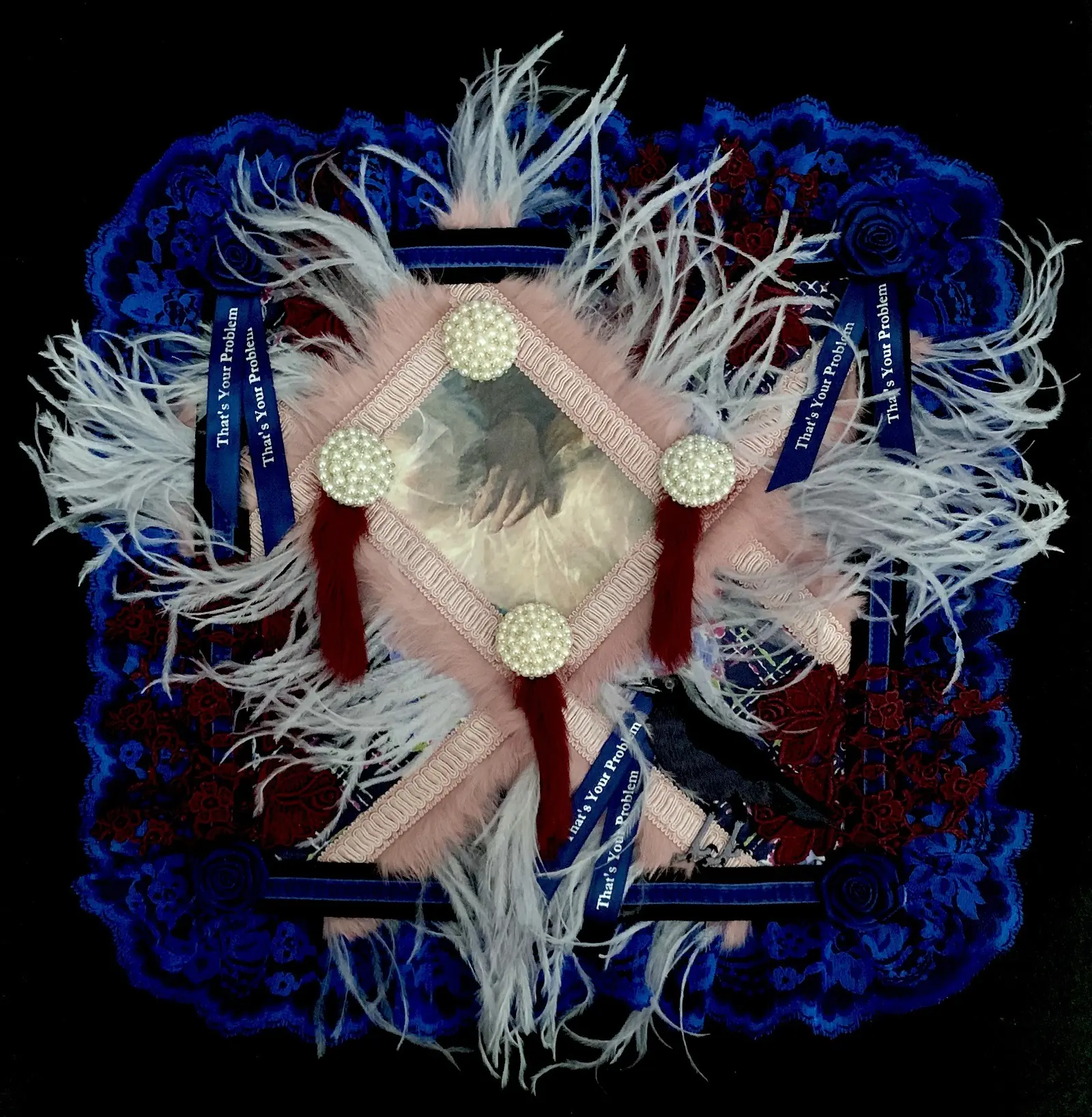

What kind of artist thinks of combining fine vintage handkerchiefs, bows, lace and tulle with outlandishly coloured rhinestones, feathers, fur and tassels (and even menstrual blood) – all topped with a rubber snake or plastic beetle? One who uses art to rid herself of hurt, anger, sadness, despair, loss and fear – that’s who

K. Johnson Bowles is a well-respected artist, and is also known as Kathy in her ‘other’ life as a CEO and advancement strategy expert in higher education and not-for-profit management. She loves nothing more than to immerse herself in creative play with her stash. But there is a reason for the almost macabre mixed media artwork that she creates. She is fascinated by the absurd, the weird and wonderful, the ironic and the sarcastic. The result is mixed media artwork through which she can exorcise her demons; those she has witnessed personally, through family trauma and in the world about us.

Kathy is not afraid to shock – her work has ignited protests and prompted claims of violating public decency standards, and has been a cathartic release through her divorce and episode with cancer.

Tighten your seatbelts – you won’t need augmented reality goggles to be stunned by Kathy’s work.

Divinity, fabric and autobiography

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

K Johnson Bowles: I learned about the Catholic church’s relic veneration when I was young. In 787 the Second Council of Nicaea passed a law decreeing every church must have a relic. I thought, “Wait. What? You mean our little 1969 modern Catholic Church off highway 54 in Durham, North Carolina, has some bit of a saint embedded in the altar?” When I asked my mother about it, the answer was “yes, likely a scrap of fabric.” My fascination with numen and the divine presence found in cloth was ignited. The concept of numen, fabric, and relics percolated within my consciousness for many years before becoming an essential aspect of my work.

After studying painting in undergraduate and then alongside photography in graduate school, I abandoned painting in favor of fiber art. In my 20s, I realized my personal beliefs were at odds with the tenets of Catholicism. I explored this tension in an irreverent body of work called Post Catholic Relics. I embellished boxes (an old jewelry box, for example) and placed inside various contemporary objects I associated with my sense of divine free-will as a woman and personal agency over my body. One piece even included menstrual blood-stained underwear to acknowledge the relief women feel when learning they are not pregnant.

The next body of work I created was called Wearing a Woman’s Life. For this series, I embellished clothes from my life to explore identity. From the actual white dress I wore when baptized to the hospital gown I wore to give birth to my daughter, every ritual of my life was marked by some 30 pieces in the series. In my early 40s, I created an installation, For Better or Worse, about my marriage. The work was filled with lace curtains, tulle, crocheted doilies, and felt. Related concepts of numen, fabric and autobiographical narrative have been constant in my work over the last three and a half decades, including my latest body of work, Veronica’s Cloths.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

As the youngest of six growing up in the 1970s, I witnessed and experienced things that didn’t make sense. Not only was I one of six children, but I was one of five girls. Watching my sisters traverse difficult times influenced me profoundly. My oldest sister, Mary, had the most significant impact on how I view the world and is one of the reasons why I focus on social justice in my work.

Mary’s life was a series of tragic injustices; she was a female incarnation of the Biblical Job. When she was in her teens, she ran away and married someone who turned cruel and abusive after she was disabled and almost died from the effects of multiple sclerosis. After a divorce and having regained the ability to walk and speak, she found love and lived with her new husband. One day her shirt caught fire while cooking, and she was severely burned. Again, she almost died. In both instances, when I saw her in the hospital, I was told my goodbyes might very well be the last words I would say to her.

Following her recovery from the burns that covered much of her body, Mary had a time of relative stability. She had two children, and she seemed well and happy. Unexpectedly, her mental health deteriorated, and she was diagnosed with schizophrenia. After this, I felt as if I had lost my sister. She was alive but never again the same person. The accounts of her severe paranoia, bizarre delusions, and dangerous behaviors were so concerning she was hospitalized several times. She again divorced and married another man who, by all accounts, had mental health issues. With him, she had two more children, but she fled the marriage because of his instability. Ultimately, my parents won a lengthy legal battle for custody of the children. My parents also cared for Mary, who was unable to work or care for herself. Sadly, at the age of 52, Mary was diagnosed with leukemia and died shortly after that.

It has taken a lifetime to reconcile my feelings for Mary. Some ten years after her death, I can no longer say that all of what happened to Mary and our family negatively impacted me. Through her, I learned about the injustices of a legal system and health system that fails people. That knowledge informs me when I speak out. While I lost my faith in Catholicism and the church, I’ve become more compassionate for the unseen/unknown plights of others. Witnessing the devastating effects of faith and fate and guilt and shame made me more prone to action and logic when confronted with decision-making. And probably most importantly of all, I learned about resilience, courage, and inner strength. These serve me in life and art.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

I attended Boston University for my BFA in painting. The training was helpful in a formal sense but unfulfilling in terms of the traditional focus on a hierarchy of art materials (painting and sculpture) and ‘worthy’ subject matter (portrait, landscape, still life). It was very limiting and rigid. Everything changed for me when I took a photography class with Professor Stephen Frank. He encouraged me to go to graduate school in photography. I attended Ohio University for photography, but when the faculty learned I could draw – and teach it – they offered me an opportunity to earn a dual MFA.

After graduate school, I was hungry to practice art. My 20s and early 30s were some of my most productive years. I was in the thick of the world of artists challenging conventions related to religion and body/sexual politics. Sometimes exhibiting my work resulted in claims that I violated public decency standards, fueled angry letters to newspaper editors, ignited protests, and provoked threats to my person. In my late 30s and 40s, I focused on my family and my career in academia. So, I made and exhibited less work. After a liberating divorce and a challenging bout of cancer in my mid-40s, I started a return to my life as an artist. Now in my mid-50s, I’m more productive and active as an artist than I was in my 20s and 30s.

Organised chaos, aesthetic intuition

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

With my current body of work, Veronica’s Cloths, each piece starts with a photograph I’ve taken whilst visiting places where old and storied objects abound; it could be a museum, church, or even a junk store. What I photograph is based on what the object triggers – a memory, concept, or feeling. It can be poignant, threatening, comforting, ridiculous, or terrifying. The images are heat transferred onto a vintage handkerchief selected for color, style, and design. I work in batches of about 6-8 pieces at a time.

Organized chaos best describes the next phase. Supplies litter every studio surface as I mix and match various objects and images until a theme emerges via the pointed combination of materials and meaning. I think of it like surrealist automatism, where I allow my subconscious to take over in an exercise akin to improvisation. I don’t self-censor at this stage; I allow whatever comes up to do so. From this ‘play,’ ideas emerge, and I begin to hone them consciously. Sometimes the concept and composition come to fruition quickly. Other times, I let ideas ruminate while exploring possible signs and symbols to incorporate. The process is about both aesthetic intuition and conscious choices of materials.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

People are often surprised to learn that I don’t use glue or any adhesives in the production of Veronica’s Cloths. Using glue to adhere various materials (from fabric to metal to plastic) onto a flexible surface is fraught. Glue doesn’t bond consistently and is more prone to fail over time or leave a residue. Glue is messy. Glue’s permanence makes it real commitment. Sewing provides the flexibility of moving items around if the composition isn’t working.

Another surprise for many people is learning that I never use a sewing machine. I don’t even know how to use a sewing machine. Yes, I could learn, but I’m not aiming for speed and perfect stitches. Hand-stitching is practical and meditative for me. Each work includes lots of layers and types of materials. Calibrating tension on a sewing machine would be a nightmare.

Sometimes I’m attaching a big plastic fly to layers of appliques, lace, feathers, and fabric. Getting a needle through the layers can be a challenge. Often a drill or an awl is required to create a hole for the needle and thread. I keep a pair of plyers at the ready to pull the needle through the layers.

What currently inspires you?

Several years ago, I experienced threats, harassment, assault, discrimination, and retaliation in the workplace. The experience inspired me to create my most recent body of work, Veronica’s Cloths.

Artistically, I’m inspired by a wide array of sources; many relate to the nature of the seen and unseen world and spiritual reckonings, such as with African power figures (nkisi) of Kongo tradition and religious shrines. I love works that conjure thoughts about good and evil, illustrate dramatic revelations, and contemplate the fleeting nature of life as with Baroque art, Mexican retablos, and 17th-century Dutch still-life painting. The earnest, profound, and obsessive need to communicate by vernacular artists also appeals to me in so many ways – they possess a sense of urgency to which I can relate.

Directness and simplicity

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

That’s a tricky question. The content of the work focuses on processing traumatic experiences; so, it is problematic for me to think about the works as associated with fond memories per se. That being said, some works represent significant breakthroughs for me as an artist. A number of these works were created during a fellowship at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (Amherst, Virginia) in February – March 2020. Being in such a supportive atmosphere, where you’re a part of a like-minded group of people focused on the creative process and where risk-taking is encouraged, naturally provides an opportunity for doing your best work.

I’ll never forget the feeling of waking up in the morning hungry to work and putting on a pair of jeans, t-shirt, sweater, drinking coffee, and walking through the landscape to the studio. Without a care about doing anything other than creating, I felt free. Some of the pieces I made there, Death by a Thousand Cuts (Mobbing), A is for Anxiety, and Betrayal (Cowards), are among my favorites for their directness, composition, and relative simplicity.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

Over the years, I’ve learned to be less direct in creating my autobiographical narratives. I look back at older bodies of work, and I see them as somewhat forced, self-conscious, serious, and linear – it’s like I was trying hard to write a memoir when I was too young to write it. Now, I care a lot less about where I fit into the artistic world and care even less about what people think.

When I feel like a piece is working, the process is more like play rather than labored/belabored. I use imagery and materials that I find fascinating without apology and use whatever will get my point across. It’s more like free-form poetry packing a punch. The methods suit how my mind operates. I’m obsessed with learning and knowing about signs, symbols, and facts. I’m fascinated by the absurd, the weird and wonderful, and the ironic and sarcastic.

I’ll continue to seek new ways to deliver my content with each work, whether via the type of imagery, design, materials, or semiotic references. I realize sometimes I gravitate to specific visual solutions, so I’ll work hard to break myself from repetition. I’ll continue with this body of work until I run out of things to say about my experience. I’ve got a lot to say; so, it might be a while.

Key Takeways:

- Know yourself – know what triggers your emotion and let it inspire your art

- Keep your eyes and ears open for inspiration – everywhere you go

- Be yourself – don’t make art to be a people pleaser

- Let go of any preconceived thoughts – be present and look at your materials and inspiration. Feel the emotions, let the subconscious take over, and then let your creativity flow

- Watch out for repetition – you may have a theme but find a way to make each piece unique

About the Artist:

K. Johnson Bowles received a BFA in painting from Boston University and a MFA in photography and painting from Ohio University. She has gone on to be exhibited in more than 80 solo and group exhibitions in the USA. Feature articles, essays, and reviews of her work have appeared in more than 30 publications including Sculpture, SPOT, and Surface Design Journal.

She is the recipient of fellowships from National Endowment for the Arts, Houston Center for Photography, the Visual Studies Workshop, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.

Since 2020, more than 100 works from her most recent body of work, Veronica’s Cloths, have been selected for publication in 48 art and literary journals across the US including the American Journal of Poetry, the William and Mary Review, and decomp journal among others. Currently, she is the executive director of the Everhart Museum of Natural History, Science, and Art in Pennsylvania.

In addition to her successful art career, Kathy is a respected writer, independent scholar and the founder of Gordion Knot Consulting – a not-for-profit company that focuses on philanthropic consulting, compliance, and communication with the strapline ‘We help enable the greater good your institution imagines’.

For more information visit kjohnsonbowlesart.com, Instagram and Twitter

What struck you most about Kathy’s work – the colours, materials, subjects, techniques – or something else? Let us know in the comments below

7 comments

Wendy E Bredehoft

These small pieces pack a punch. Appreciate the context and antecedent references. All of this comes together in a personal way in the work!

Leanne Rogerson

Key takeaways…Know yourself, Be yourself. Two things I am starting to acknowledge in my journey of self discovery and understanding the parallels that exist within my art. Thank you for sharing so that we all can grow the courage we need.

Marcus

This interview is as empowering as your art. Beautifully touching and resilient, it’s incredible how you managed to convey so much through images and textiles. The vibrant colors, the emotions surrounding the imagery you used. Handkerchiefs are so delicate and yet I can see nothing but strength in these pieces. This is incredibly cathartic, thank you.

kit sutherland

I think you are one gutsy lady. So important that you have found a means of expression and release that fits you personally. What other people think of your work is truly secondary though I am glad your skill and imagination are recognised. Thank you for sharing and encouraging others.

Sarah I R Pyke

I was really fascinated to see your process of dealing with trauma. I too have been working on an autobiographical piece. It is a visual memoir in panels so your methods of working are hugely relevant to me at this time. Thank you for a very exciting interview and body of work.

Darlene Olivo

Dear K, I see such similarities in our stories: I, too, was one of six, one of five girls–but I am the oldest. I, too, turned my back on the oppressive Catholicism of my family, and use that in my art. It is an honor to view your work. I salute your courage and creativity.

rose

your installations are troubled and troubling, thank you for sharing your deeply personal pieces of work. I am sure they will allow other artists to re-evaluate their own thoughts and feelings, maybe create new pieces which truly represent what they are experiencing and face things head-on.