Textile art is often all about the texture. The trick is to work out the best way of using those tactile qualities to your advantage. In her quest for texture, Jean Draper has found that observing the minute details of her subject matter can really help to inspire.

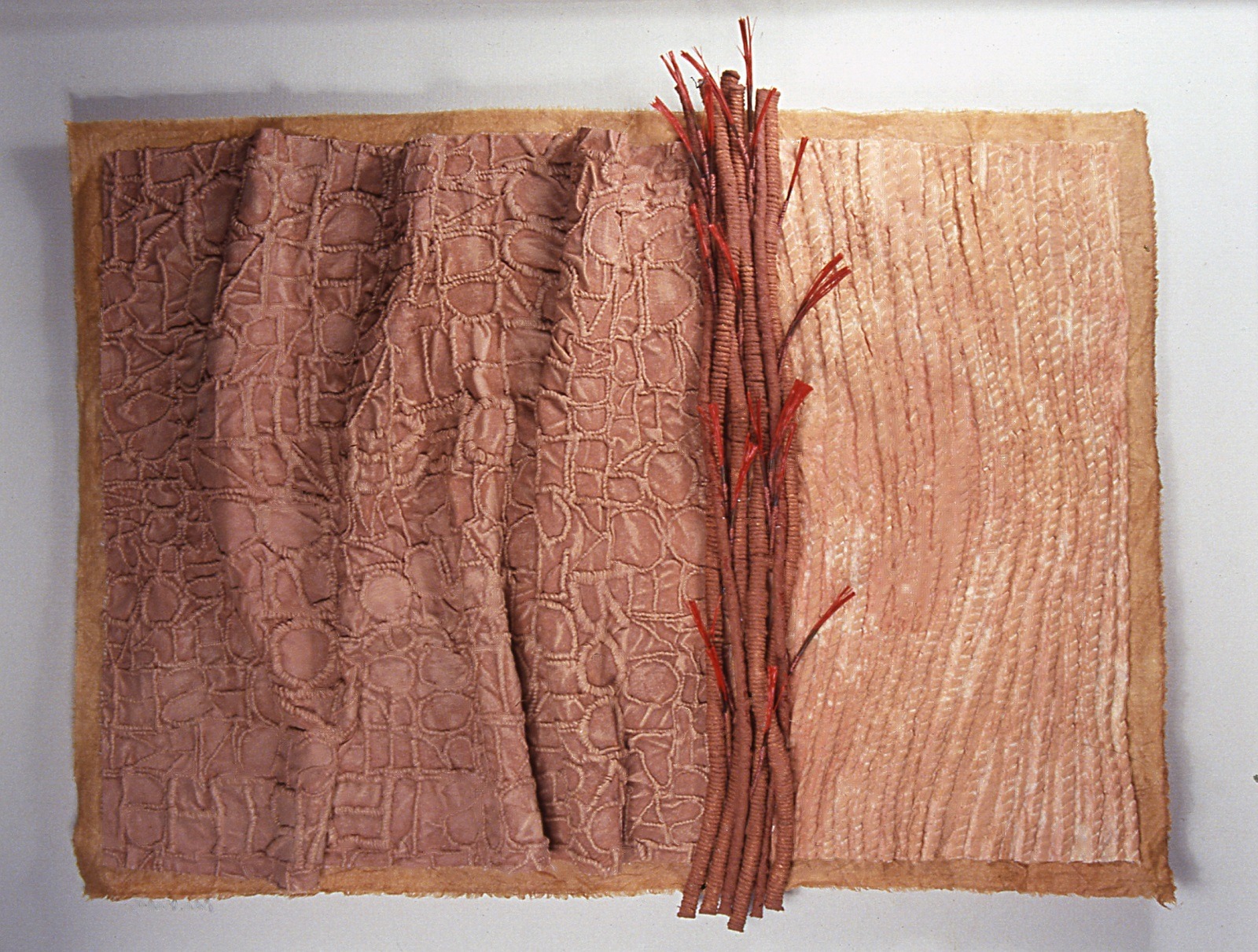

She begins her projects with an extensive period of research, drawing and sampling, always making sure she is hyper-aware of her surroundings. Her work is often based on the close observation of the bold features, shapes and patterns found in barren landscapes, formed through erosion and wear. Jean uses these interesting details as the basis for her work, in which she explores the themes of conflict, social injustice, regeneration and recovery.

As a member of the 62 Group and the Textile Study Group, Jean has exhibited widely. Her work is held in public and private collections and she is also the author of two books, Stitch and Structure (Batsford, 2013) and Stitch and Pattern (Batsford, 2018).

Jean is a stitcher who is not afraid to tackle difficult subjects in her work. In this interview she shares a few of her favourite pieces and the ideas behind them. Find out how she portrays both the physical beauty and the intense emotional aspects of a place. You’ll also learn more about Jean’s more recent sculptures made of self-supporting networks of wrapped, stitched and layered thread; stitches in thin air! These stunning creations are based on the patterns found in areas of impenetrable plant growth, which she uses to represent the restrictions and barriers affecting many people today.

Sewing started at home

TextileArtist.org: What initially attracted you to textiles as a medium? How was your imagination captured?

I have been around textiles all my life and liked handling them as a small child. Having a needle and thread in my hand feels very natural to me and I have always enjoyed sewing. But the real attraction to textiles as a medium came later when I was introduced to the breadth of possibilities afforded by the in-depth study of textiles, whilst at art college. This was when my imagination was first aroused; this feeling has never left me.

What or who were your early influences and how has your life/upbringing influenced your work?

My mother was able to sew, knit, crochet and embroider. In fact, these skills were not just pastimes in our home, but very necessary activities. My mother was able to create a comfortable, well-furnished home and dress herself and her three daughters beautifully on a small budget. I learned alongside her, not only how to make things but also sorting and counting, by organising piles of buttons and compiling rudimentary sewing sets from the contents of her sewing basket!

As a result, at school, I found that learning to sew was not the dreadful problem others girls found it to be. My father was a strong and supportive influence too; beyond all my expectations and hopes, he encouraged me to attend art college in order to pursue a career in art.

What was your route to becoming an artist?

My route to becoming an artist began with a four-year training in art college and then a further year at London University Institute of Education, where I gained my teaching degree. This was just the beginning of my education; I discovered that gradual learning through lifelong, constant practice is the route to becoming an artist.

In addition, I am extremely fortunate to have met and worked with some hugely influential people. Initially, I identified only as a teacher but my American friend, Barbara Lee Smith, not only encouraged me to call myself an artist but engaged with me in serious discussion about my work and that of other artists.

Awareness and observation

Tell us about your process from conception to creation

My work process is pretty all-consuming in that I think of work constantly! I am always looking, visiting museums and galleries, drawing, making notes as ideas occur, and stitching, both samples and actual pieces.

The very beginning of this process is based on awareness and observation, responding emotionally and physically to my surroundings.

My subject matter is firmly based on places and people. I find inspiration in stark, barren landscapes found in the UK and abroad. Although at first appearing empty, these places abound with arresting detail and dramatic sculptural features, exhibiting shapes and textures caused by the effects of time and the harsh environmental conditions. These features include monolithic rock formations, material evidence of the people who have lived and worked there, extraordinary plant forms, and often signs of change and destruction.

The ability of these raw places to slowly recover and regenerate, holding memories, has a considerable metaphorical significance to me. I try to express this in my work.

Because I always work thematically, I rarely work one piece at a time, preferring to have several pieces at some stage of development; one work follows on from another. These pieces are pinned up for consideration as I work and are sometimes cut up and reassembled if I am not satisfied with the way they are progressing.

Tell us a bit about your chosen techniques and how you use them

Three textile study trips to India had a radical effect on my stitching. I became more aware of new and exciting colour combinations, as well as the rich and spontaneous pattern-making, stitching, quilting and recycling practised there, particularly by the village women. I saw how one simple stitch technique could be stretched and adapted imaginatively. I have since chosen to work with fewer stitch types, hopefully in a more meaningful way than before.

I find stitching is a very physical, gestural process; rhythmic and repetitive. I like to use one simple stitch intensely over a whole surface, creating a cohesive surface structure that completely alters the feel of the fabric.

But whilst developing my technique is important, it is always secondary to the ideas that emanate from intense observation, together with drawings which initially provide information and then lead to ideas for translation into my stitched textiles.

What currently inspires you?

Throughout my working life as a maker I have been interested in portraying different aspects of place; not simply the beauty of a particular landscape but, more intensely, other emotional, atmospheric and dramatic qualities that have affected me. These have sometimes been associated with the people close to me, but also with the history of an area and the marks left on the land by people, long gone, who have lived and worked there in the past.

I have spent many hours in museums studying the material evidence related to a place and its people. Although the appearance of my work has changed over the years, my subject matter remains firmly based on places and people.

The wide range of beautiful artwork, artefacts and ritual objects made by people who live close to the land continues to be a revelation. Some handcrafted items, such as baskets, have directly inspired me to make objects, like the series of small three-dimensional forms that are based on natural plant forms found in desert regions.

Awareness of the symbolism and meaning within the work made by indigenous people is very affecting. This has now become an aspect of my own work, where a title is sometimes a metaphor for my feelings.

Forbidden books

Tell us about a piece of your work that holds particularly fond memories and why?

Several years ago I witnessed the immediate aftermath of a huge and devastating forest fire in Arizona. This experience had a profound effect on me and I have since made quite a lot of work about burned books, representing the destruction of thousands of trees from which paper would have been made.

I made drawings in various media, of whole areas and of details, too. One complete sketchbook was devoted to the development of ideas for work on this subject.

The first series of resolved work was called ‘Burned Books’ in which handmade book sculptures were used to express the loss of books. I put blackened thorns and spikes on them, emulating some of the remaining shapes and details that I had observed. The series had a secondary title, ’Books Can Be Dangerous’, initially because they were too spiky to open, but also because I was thinking about how ideas and principles expressed in books can be considered dangerous enough for some societies to ban or destroy them.

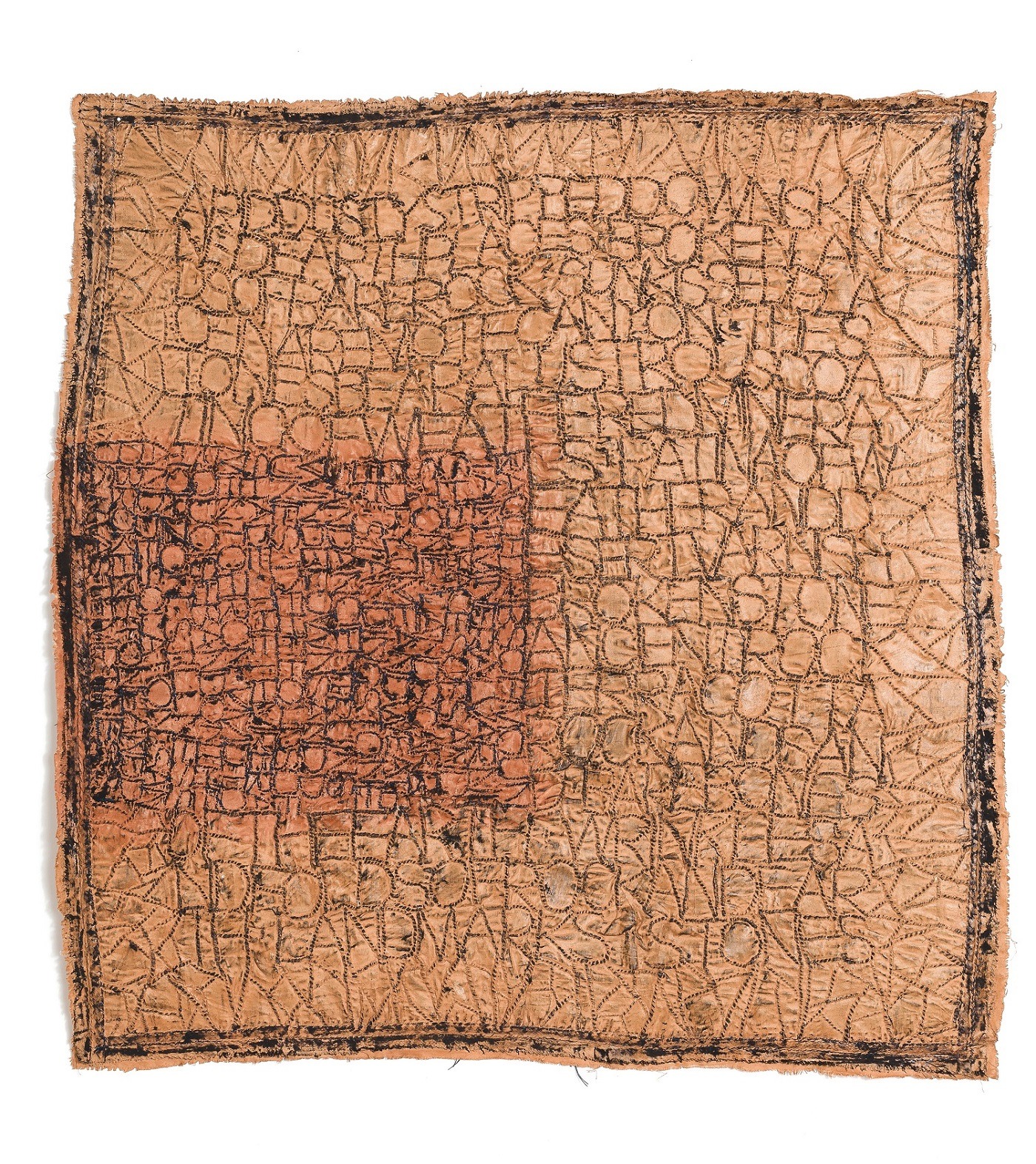

The installation called ‘Forbidden’ was made in 2017 in response to a challenging title,’Conflict’, set by the Textile Study Group for the exhibition ‘Dis/rupt’ in which we were encouraged to make work that disrupted our normal practice. My rationale was based on the power struggles, lack of understanding and the fear and prejudice that is demonstrated in all levels of society, including nations, governments, political parties, ideological and religious factions, or even within and between neighbourhoods.

These attitudes prevent peaceful coexistence and, in many instances, actively promote conflict. Throughout history there have been many instances where the important symbols of a weaker or conquered culture, such as art, architecture, religious icons, language or books, have been destroyed in order to crush or to subjugate.

In this installation I explored the sculptural potential of the altered book form, investigating the emotional aspects, for myself and the viewer, of making and presenting a collection of books that are partially destroyed, mostly by the aggressive act of burning. I hoped that the wasteful destruction of books, originally printed to disseminate knowledge and ideas, but now violently damaged, gagged and unreadable, would be a powerful one.

‘Forbidden’ represents a major leap forward in my work in that I gave myself permission to make a strong, disturbing political statement, which is not polite or pretty.

How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

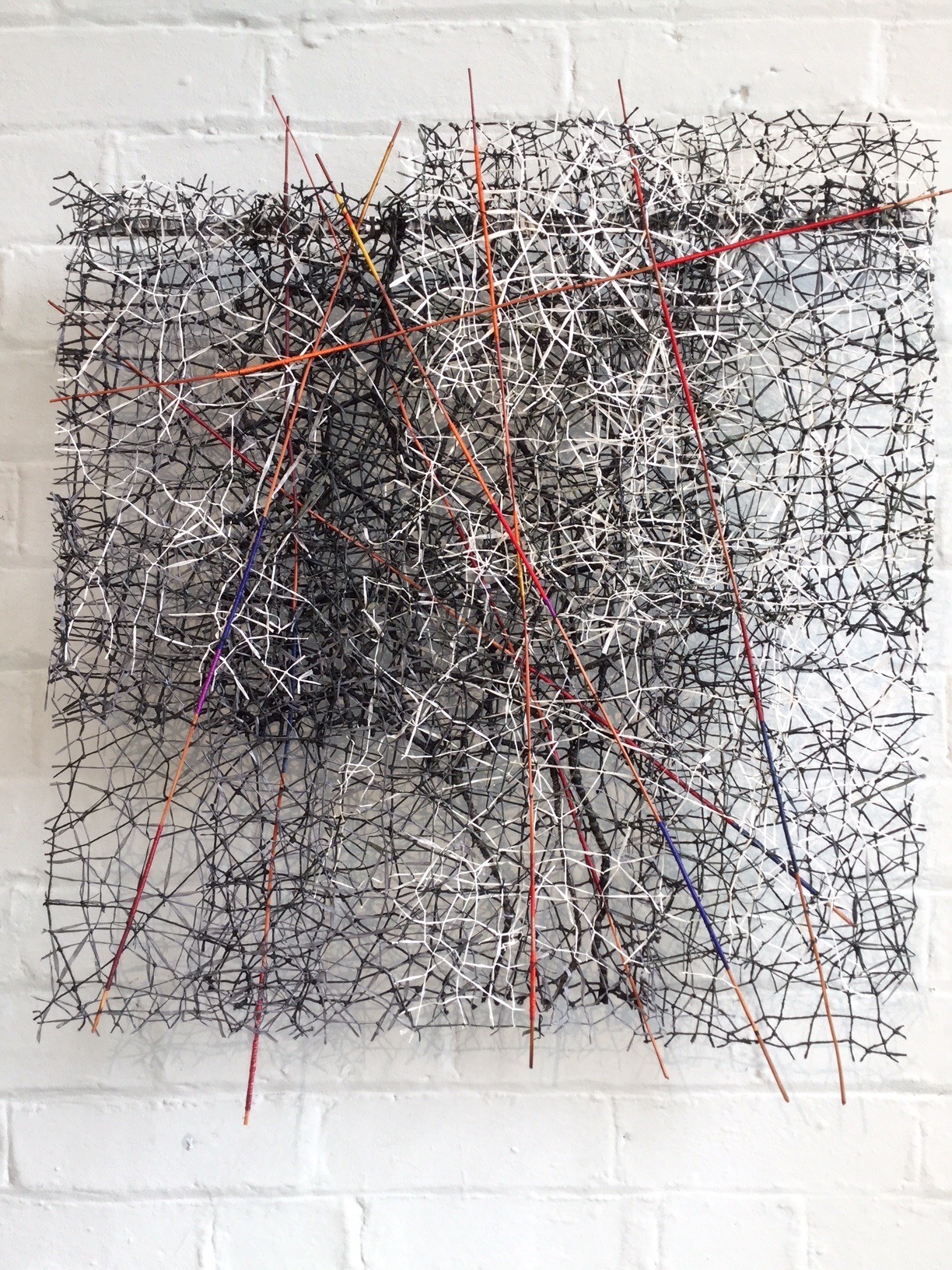

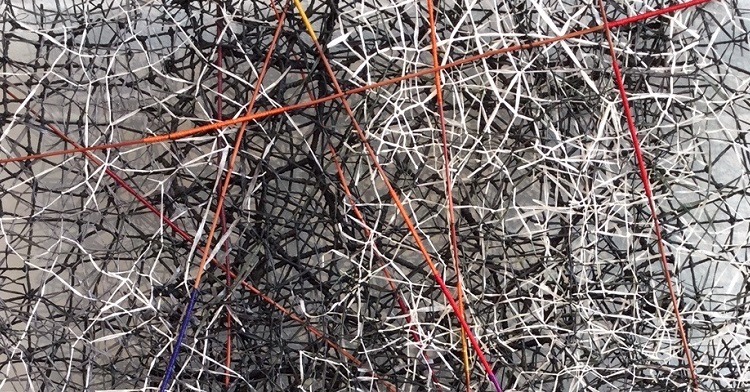

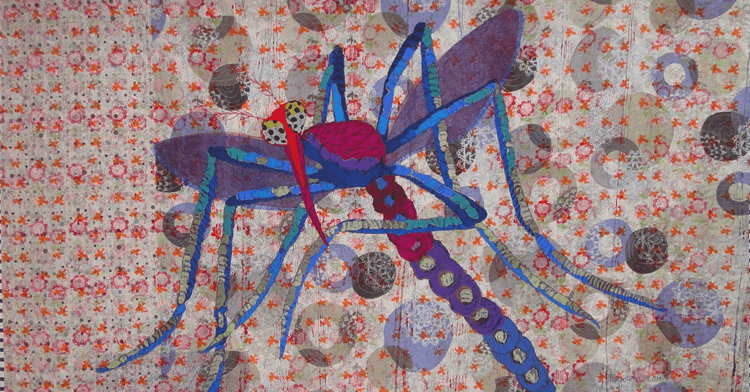

Continuing with themes relating to my concerns for justice and other social issues, recently I have been making work consisting of many layers of stitched meshes or nets, to represent unfair restrictions and the barriers to growth and personal freedom suffered by many people.

Starting with reference images of harsh impenetrable plant growth seen in desert regions, these pieces are made from robust threads such as hemp, linen, pineapple fibre, wire, paper, sisal, coarse cotton and ramie, sourced because they seem appropriate for the harsh nature in which some of these tough plants grow.

After completing extensive drawings of the plant forms, I then make numerous mesh networks using large-scale needle lace knotting techniques and wrapped threads. The colour and weight of the lines is very important, as is the dynamic and direction of the stitches. A great deal of time is spent arranging, rearranging, considering and assessing the effects of colour overlays before finally assembling them to form deep, self supporting thread textures held together invisibly.

I can visualise a number of directions, including three-dimensional work, developing from this point in the future.

Did Jean’s work resonate with you? If so, why not share this article with your friends using the links below.

9 comments

Zeni Shariff

Art is an excellent way to express our inner feelings and gratitude.

Marianne

Dear Jean,

Thank you very much for your fantastic textiles – except one…

Books are sanctities for me.

And (I’m an old one) remember the awful burning of books by nazis in Germany and elsewhere.

I think highly for your art, but I should like if you consideration this kind of sad deed of this era – the II. world war’s time.

Best regards

Marianne

Liz Curtin

Absolutely amazing work! Thank you for a wonderful article with great photos of Jean’s work.

Sharee Dawn Roberts

Wow. Wow. Wow.

Marty zjonas

One of my greatest mentors. I miss our yearly get together. Love your new work.

Margaret Roberts

Thank you for the most wonderful interview with Jean. It was so inspirational and even though I am now 86 I shall be lifting the bar on my next embroideries. I have been following Jean’s work for many years through the wonderful library of the Embroiderer’s Guild of the A.C.T., Canberra, Australia and completed a piece inspired by Jean’s overcast stitching. It was good to be reintroduced to Barbara Lee Smith as she stayed with me when she came to Canberra to conduct a workshop many years ago.

Margaret Roberts

Angela Thorpe

Wonderful use of natural fibres. What an adventure. 🙂

Sharon Combs

These are absolutely wonderful. And the diversity is amazing. Wissd’s h i could see her actually mas king these.

Kathleen Garraway

The freedom of Jeans work resonates with me.