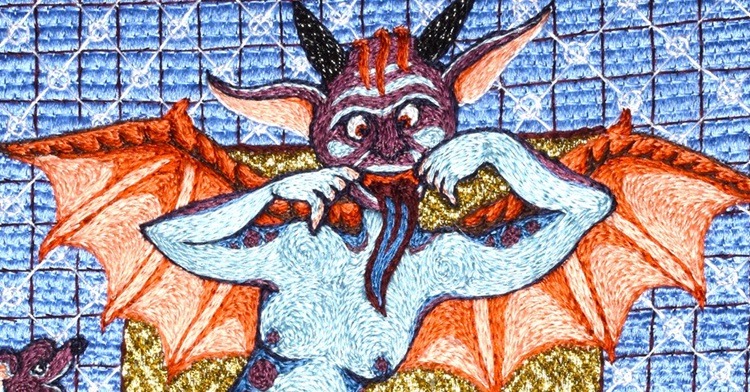

Did you know that medieval embroidery can be humorous and a little risqué? Take a look at Tanya Bentham’s unique portrayals and you might be surprised at what you see.

As she got to grips with the laid and couched work and rich lustre of silk filament threads, Tanya discovered plenty of material in the 13th and 14th century images that appealed to her quirky sense of humour. So much so, that her third book on the subject is called Naughty Medieval Embroidery.

Tanya was first attracted to medieval embroidery in her teens, well before how-to books or YouTube tutorials were widely available. As she taught herself to replicate maidens, knights and dragons, she added extra interest with her own modern and humorous twist.

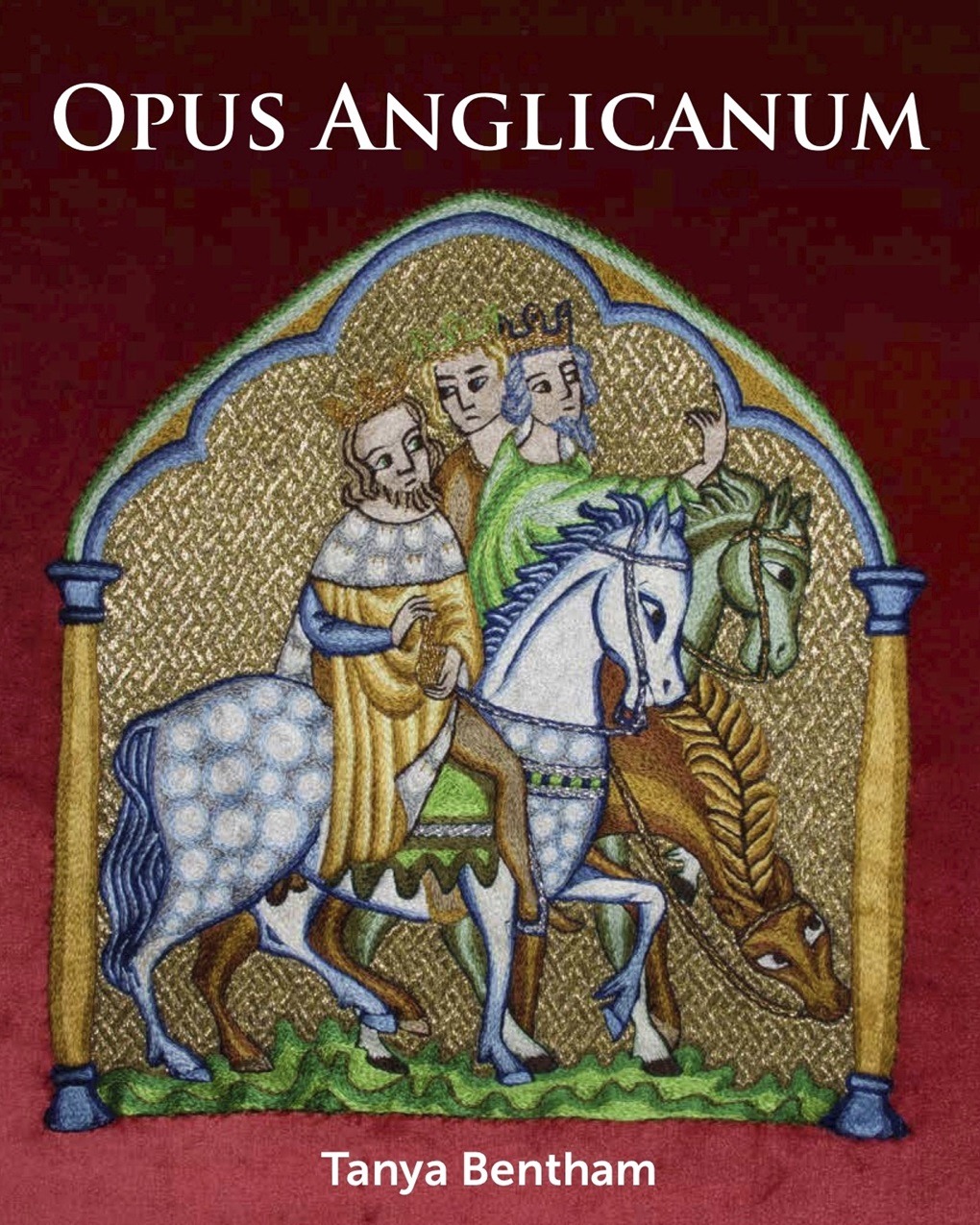

Although Tanya dyes, spins and weaves as well, her first book Opus Anglicanum features the style of medieval embroidery that is her trademark.

Tanya’s unique variation on this era sees her adding a character with a Wallace and Gromit-style expression, stitching a rat eating McDonald’s fries, and features her own boyfriend holding a can of cat food.

Sophistication of silk

Tanya Bentham: There’s a lot of humour in medieval art and that’s largely what I’m drawn to. Subject wise, I love the silly, the rude and the downright bizarre.

Stylistically, I’m drawn to the earlier style of opus anglicanum, because it’s far more sophisticated than the simplified style that was introduced after the Black Death. Understanding the original purposes of opus pieces is important in understanding why things are done the way they are.

At its most simplistic, opus could be described as just split stitch and underside couching combined, but it’s so much more than that, and, the deeper you dive, the more you realise how flexible the rules are.

For me, opus is highly material-dependent. You can only call it opus anglicanum if you use a silk filament (also known as flat or reeled) silk. This is because, where most styles of embroidery rely on gradations of colour and shade to model a three dimensional shape, opus depends upon light reflecting off silk.

Only a filament silk plays with light with enough intensity to model a three dimensional shape.

Even a twisted silk doesn’t bring the same light to the work, and cotton brings practically none.

Tanya Bentham, Textile artist

Much is made of the gold in opus, adding richness and lustre, but I think the role of silk is largely overlooked because the originals are so degraded now.

At an exhibition at the V&A Museum some years back, I saw people pressing their noses against the glass to examine the individual stitches, but when I teach I tell people that you should never be able to pick out a single stitch. It’s about banked masses of stitch and how they manipulate the light.

I think the only other hard and fast rules are that, although you can have silk velvet or silk showing as negative space in a composition, you should never ever see linen, and that underside couching should always be a filling stitch – it’s not meant to be used as a single row.

Stitches and colour

Most surviving opus pieces have two main stitches – split and underside couching, and laid and couched work with split or stem stitch when working with bayeux or laid and couched work. There are a few ancillary stitches like trellis couching and surface couching, and a lot of subtle refinements to basic technique. For me, that simplicity creates a visual harmony allowing the eye to focus on the image.

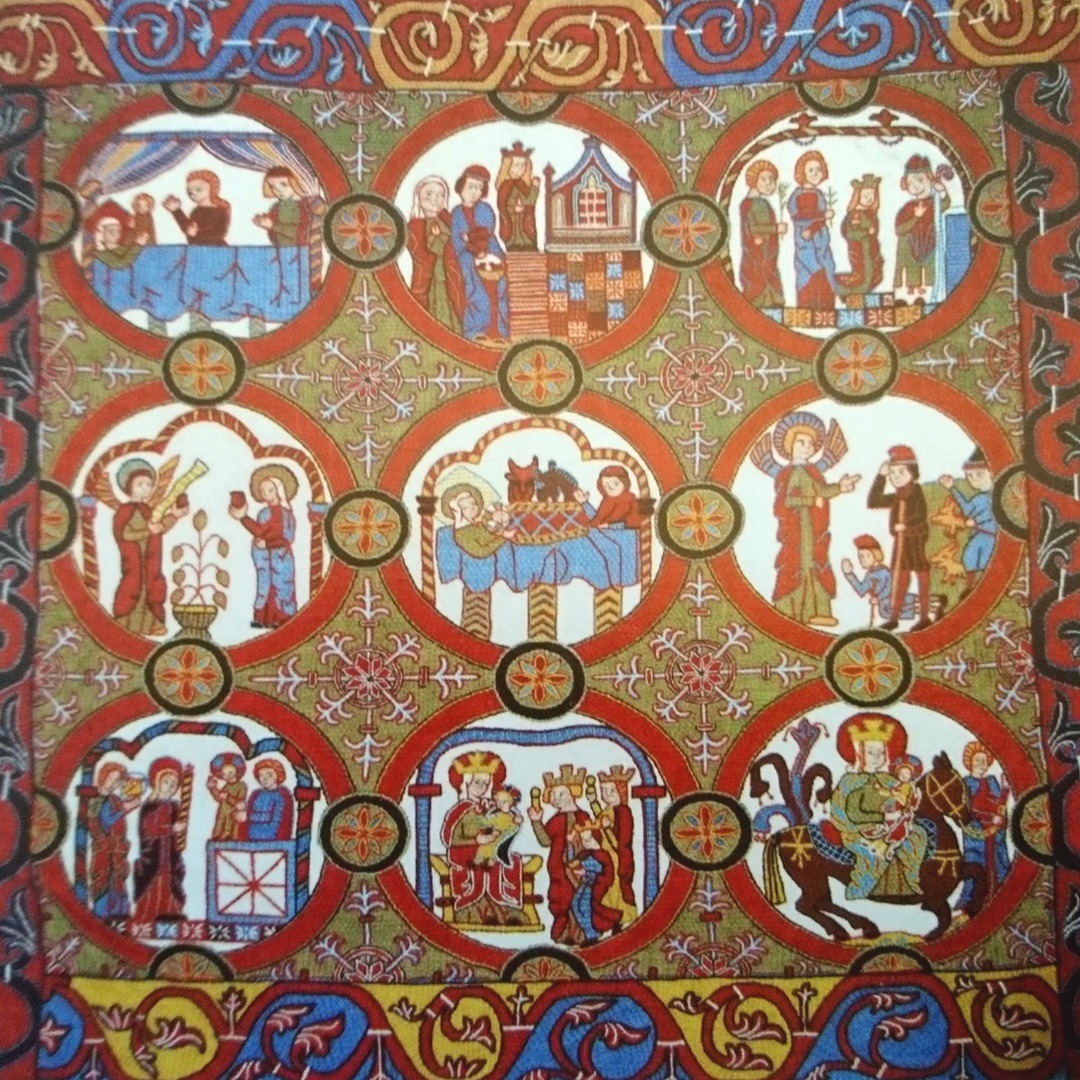

The same applies to the use of colour in medieval embroidery. If you look at a big piece like the Reykjahlid Antependium, which is over a metre square, it uses only about eight colours, but there’s a distinctive rhythm to the way they’re used. The Antependium was an important formative piece for me as an embroiderer, not least because it began to teach me, with its mix of opus faces and wool background, that there are no hard and fast rules to medieval embroidery.

It was the piece where I got rid of all my commercially dyed wool threads and began to work exclusively with natural dyes. The fact that you can’t colour-match if you run out of a batch has made me much more conscious of how I use colour in composition. I will deliberately limit the number of colours I include in an opus piece (where I use commercially dyed silks) as a way of making the finished result look more medieval.

Modernising the medieval

If you’re too careful about observing the sanctity of an original image, you can take the joy right out of it. There really is no such thing as an exact replica because every artisan holds their brush or needle in their own individual way.

I understand the Middle Ages, but my mind is that of a 21st century woman. I tend to see the humour in images and I like to draw that out and play with it.

Tanya Bentham Textile artist

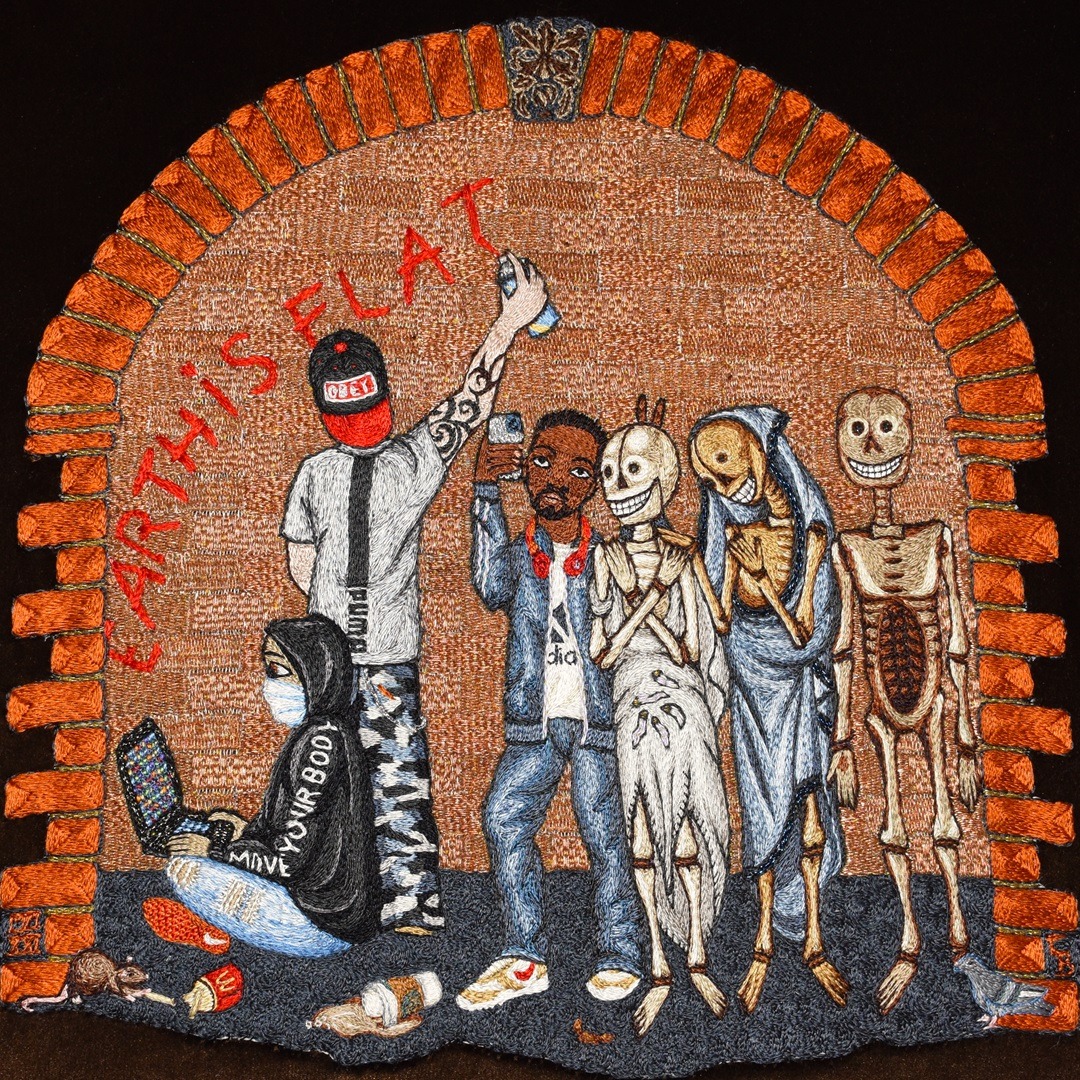

A good example of adding a modern twist would be The Three Living and The Three Dead. While writing my book, Opus Anglicanum, I was reminded of the medieval tale, in which three young men are not living good lives – drinking, gambling and whoring instead. They set off into the forest and meet three walking dead who tell them: ‘We were once as you are now, and in life were so wicked that death will not take us, and now we are condemned to walk the earth for eternity’. The young men at once see the error of their ways and reform their lives.

I re-read the tale and thought your average 21st century ne’er-do-well wouldn’t learn anything from such an encounter, and the idea grew from there. Because modern young men don’t tend to venture into the countryside much, I transferred the tale to a grubby inner city railway arch, with a green man keystone as a forlorn reminder of the countryside, and some urban wildlife at their feet (the rat eating chips is my boyfriend’s favourite of all the images I’ve ever sewn).

I used the three dead from a medieval illustration of the tale and then did a lot of research into urban streetwear for the three living. I admit I chose mainly for irony and humour – the graffiti boy has a hat that says ‘obey’, and the seated figure has a hoodie that says ‘move your body’.

The background to the piece also stretches the boundary of medieval technique. Medieval counterpoint couching uses the same stitch in two directions (horizontal and vertical) to create pattern through textural contrast. But to get the brick effect I had to introduce a second texture, also worked in horizontal and vertical, for the pattern to work. I deliberately worked in a real copper passing thread because I was intrigued to see how it might weather over time and add to the general grubbiness of the scene.

My favourite piece is usually either what I’m working on right now, or the piece I’ve just finished. At the moment it’s Cat Daddy. My partner, Gareth, and I were sitting in bed last year reading the Sunday papers, and The Times had a spread on the restoration of Lincoln Cathedral. I looked at the wonderful Romanesque frieze of Daniel in the lion’s den, nudged Gareth in the ribs and said: ‘That’s you, that is’. And so Daniel became a ginger Gareth, his hands went from signalling pax to holding a can of Whiskas cat food and a feather toy; the cats became my blue Maine coon, Branston; his Bengal, Trubble; little black and white Sam from next door; plus one random ginger lion.

The right materials

The filament silk I mainly use is from Devere Yarns for their good range of repeatable colours, but when it’s just for me, I will often use Midori Matsushimas Japanese silks, or old weaving silks from factory shops, where you can often pick up non-repeatable filaments.

I do have a few antique metal threads in my stash, which I often use when I want the gold to tarnish. I used this for the gold mortar between the bricks on the Three Living and The Three Dead, but largely I rely on threads from Benton and Johnson, and I’m sure I drive my supplier crackers with my constant demands for new colours.

As base fabric for opus I use a fine ramie, doubled. Vegetable fibres are often lumped together both in period and in later identification, but the main reason I use the ramie is that I can’t get a linen with 90 thread count, and the fine thread count allows really accurate needle placement.

When I want to use twisted or plied silks I will usually source them from weaving suppliers, which have a more limited range of colours but are fantastically cheap.

Some years ago I got rid of all my commercially dyed wool yarns and began to dye my own using natural dyes. I dye some silks as well, but about once a year I will dye about 10kg of crewel wool for both my kits, classes and personal use. I use natural dyes, but I don’t bother with rosehips or cabbages – those are really stains rather than true dyes. I use mainly woad or indigo, weld, madder, walnut and cochineal. These dyes have a historical precedence because they produce reliable colours that are reasonably light and colour fast. This allows me to get closer to what the original colours of medieval embroidery actually looked like. One of my pet hates is reproduction embroidery carefully colour matched to what the threads look like today.

Draw before stitch

My process depends upon my mood and what I’m doing. The Antependium is a pretty straightforward replica. I drew the template directly onto the fabric. I don’t actually like drawing very much, so it’s a step I’ll skip if possible.

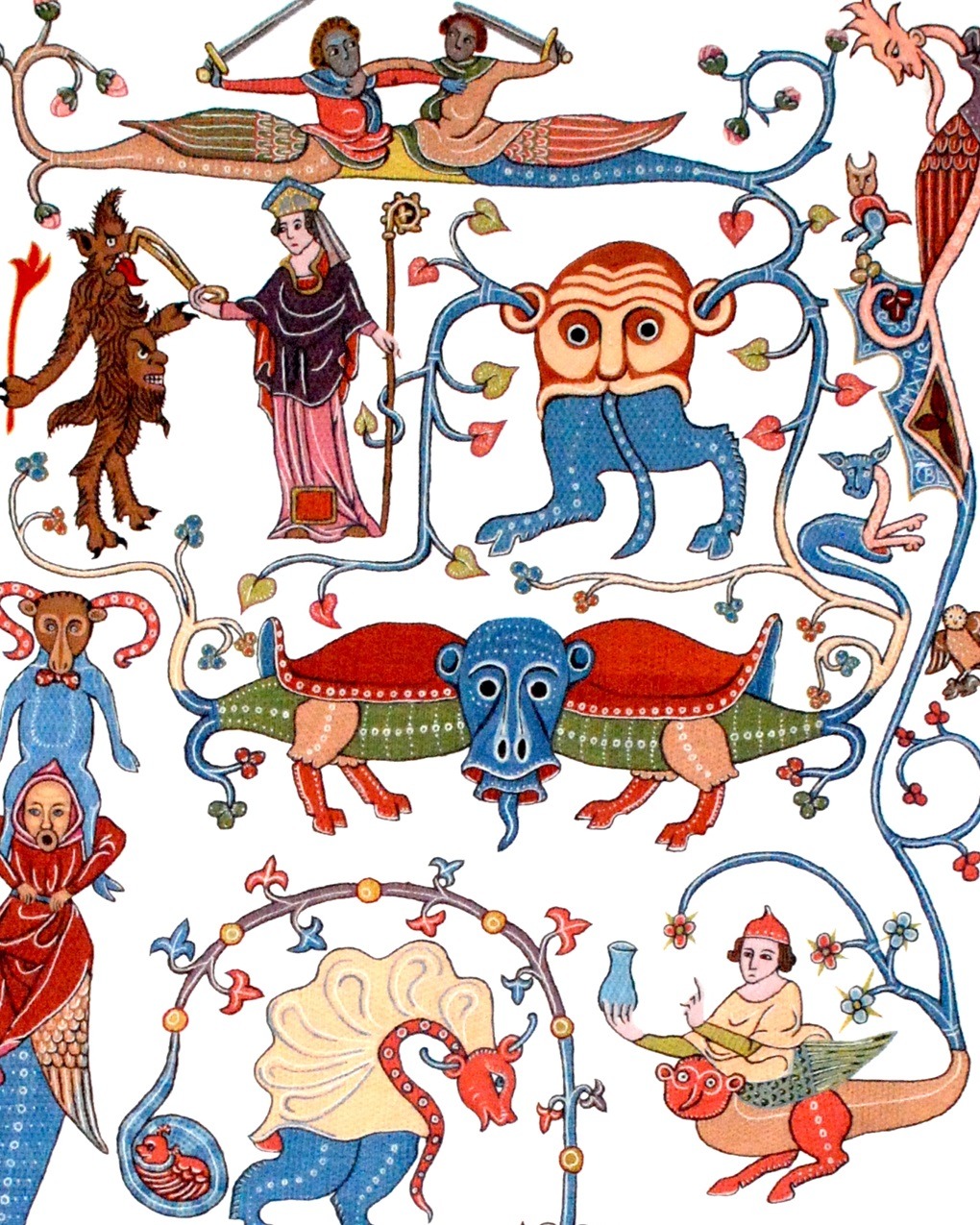

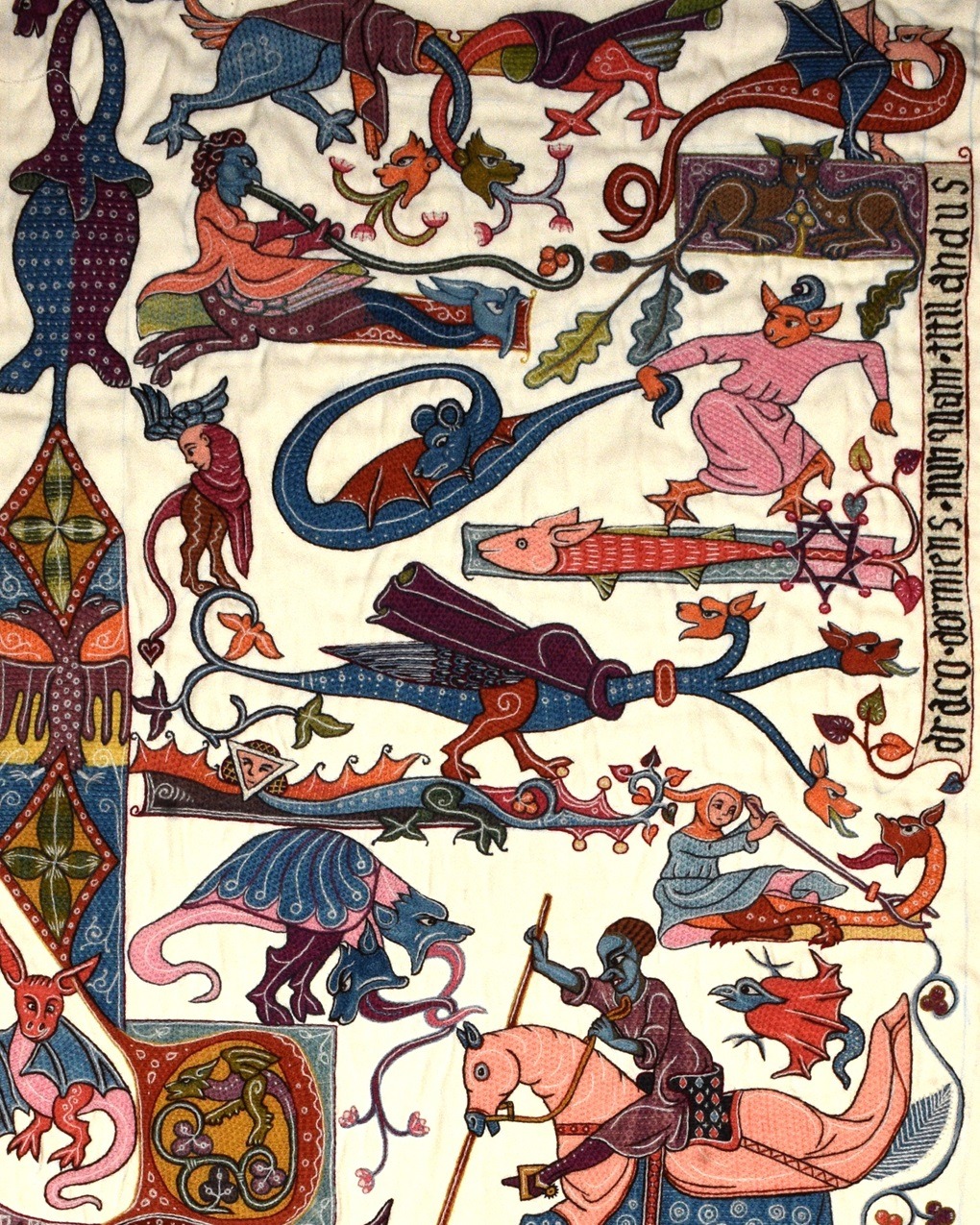

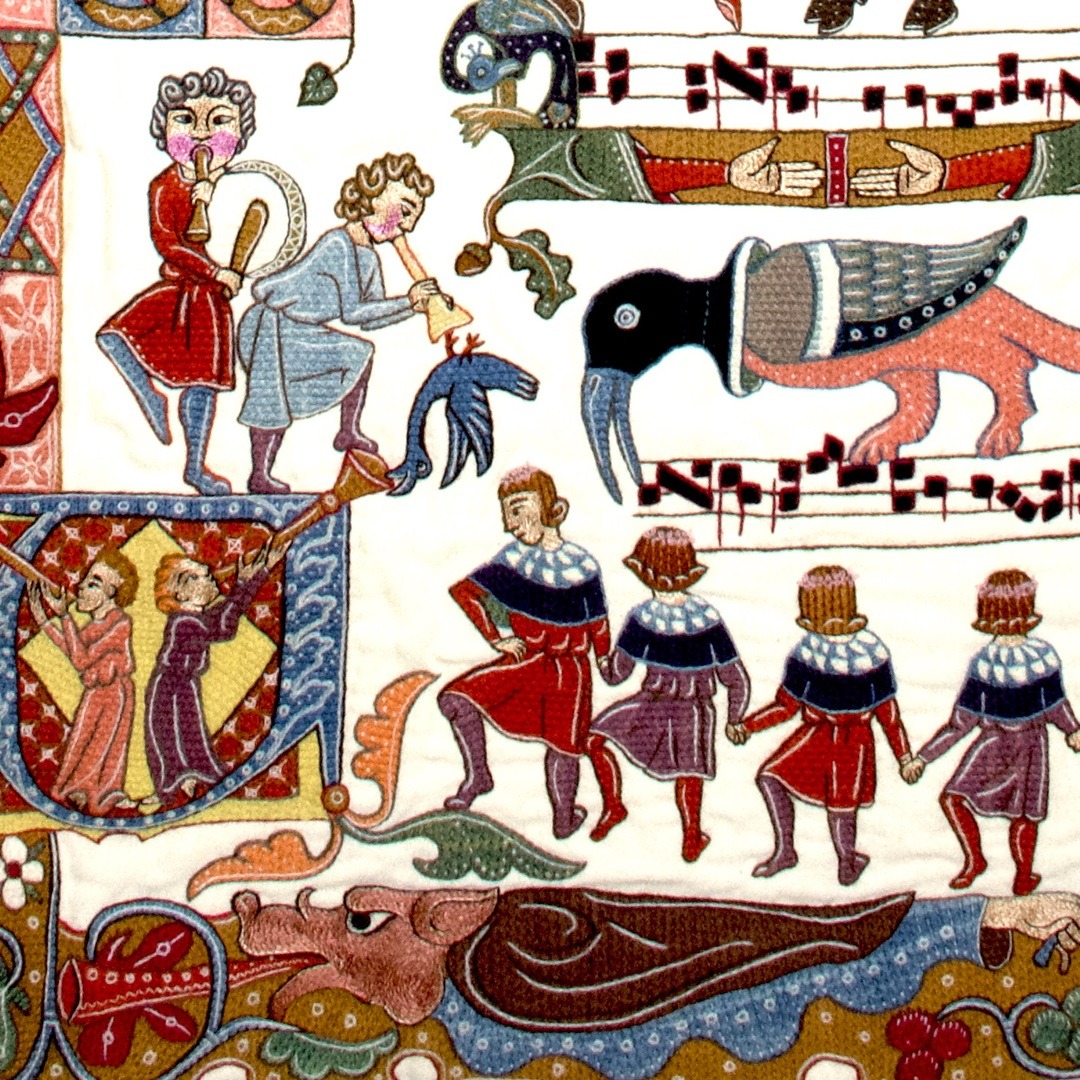

With the big Luttrell fantasies I sit and browse my replica copy of the psalter, taking mobile phone pictures of anything that fits my theme, which I then print out. I tape the canvas, about 92cm x 183cm (3ft x 6ft), onto a big sheet of plywood in the living room and then draw the whole thing freehand, directly onto the canvas. It takes about three days.

If a design is intended for a kit I’ll draw it. If it’s something really complicated like The Three Living and The Three Dead, then I do quite detailed drawings but, even then, they often need tweaking part way through.

Teaching and writing

I’m glad I taught for a few years before writing my books – I taught for years at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, at Leeds University’s International Medieval Congress, and at various other venues, as well as running my own online classes. Teaching opened my eyes to all the different mistakes people can make, and that’s made the troubleshooting sections of my books a lot more user-friendly.

All of my books are structured like courses. They start with a beginner’s project and each subsequent project adds another layer of knowledge and technique. I felt this was especially important with the first book Opus Anglicanum because, although there are lots of academic books on the subject and plenty of goldwork books that mention opus techniques for a page or two, this is the first proper deep dive into the technical aspects.

My Opus and Bayeux books are focused on technique, but the third includes many different medieval techniques. Naughty Medieval Embroidery is probably closer to the original concept as it includes lots of different techniques, centred around the rich seam of silliness and filth that runs through medieval art.

I think my favourites from my third book are the Bonnacon and the Danse Macabre. The Bonnacon is one of those forgotten beasts from the bestiaries, a wild bull with ingrown horns who defends himself by emitting a vast toxic fart cloud. The illustration I chose has the bull with a very cartoonish grin that’s very like the Wallace and Gromit characters. The Danse Macabre is an opus project which incorporates a complex background using a wonderful luminous sky blue, and I’m an absolute sucker for colour.

Moving on from Bayeux

I was partly raised by a grandmother who was a knitter. She hated all forms of stitching and pretty much despised art – she made no secret of hating my mother who was from a family of artists and artisans. I don’t think my upbringing was particularly arty, even when I was with my mum. I did art at school and managed an A at O-level, but I barely passed A-level art due to two warring teachers who continually contradicted each other.

Historical re-enactment is quite a creative space, but also confining in that you have to adhere to standards of authenticity. It’s a good place to learn technique and perseverance, but there isn’t much scope for creativity in design – because someone will notice if your medieval saint is carrying a mobile phone.

Like most people, I started out doing bits of replica Bayeux Tapestry. My display was pretty good, but I lost count of the number of people who saw my embroidered tent from a distance, scoffed, ‘not another Bayeux Tapestry’ and stomped off.

Tanya Bentham Textile artist

I’m grateful for that experience now because it encouraged me to explore other types of medeival embroidery, like convent stitch. I made replicas of the Malterer Embroidery, which was great because it contains that narrative element of medieval art and lent itself to storytelling while stitching – always a good way to draw a crowd.

Living style of embroidery

I’m disorganised and tend to live in the moment, but I started my blog as a promise to myself to take my work more seriously. I wrote a few magazine projects and did some teaching as a way of building up a CV with which to approach a publisher. No one makes much money from this type of book, but it serves to get your name known, and since the publication, I’ve been speaking more and teaching for embroidery groups.

I also decided to exhibit more, because I want opus to be seen as a living style of embroidery. I’ve had a couple of solo exhibitions, as well as taking part in various group exhibitions across the country as an artist, rather than simply an embroiderer. My work was also part of the Broderer’s Exhibition in 2023 and the Fine Art Textiles Award in 2022.

Relaxed fluency

As I’ve grown in confidence I’ve become more interested in embroidery as art, rather than as something which simply replicates an historical artefact. Imagination plays more of a role in my work now, even though I’m very strict about staying within the confines of historical technique.

Technically, I think I’ve got what Grayson Perry calls ‘a relaxed fluency’ in as much as I’m very much in command of what I do.

If you have to do 10,000 hours to become an expert, then I’ve done that several times over in medieval embroidery – it allows me to make my images do what I want them to do. It makes me more playful.

Tanya Bentham Textile artist

I never know where my imagination will go next, but I’m very much in love with the technical possibilities of opus anglicanum as a living style of embroidery, and I can’t see that changing any time soon.

Explore the possibilities

I’m self taught. When I began stitching in my teens there was no one teaching or writing about medieval embroidery in any detail. Laid and couched work – I dislike the name bayeux stitch, it makes people think that stitch was only ever used for one piece – is pretty easy to learn and it’s still how I’d recommend people start before moving on to opus. I didn’t really do any opus until I was able to afford proper silks and metal threads, which were hard to find on a student budget in the 1980s.

I actually studied classics, so that didn’t help much, although I’m hoping to start an opus piece inspired by classical sculpture and Japanese kintsugi later this year.

I think there are a lot of people who dabble in a lot of styles and never really pick one, and in doing so end up with a huge work-in-progress pile (sorry if I’m calling anyone out). Even qualified tutors can be jacks of all trades and mistresses of none.

I think if you want to be good at something, you need to finish what you start. Find a style that interests you, whether it’s medieval embroidery or goldwork or beading, and explore every tiny detail of it.

Tanya Bentham Textile artist

Don’t just skim the surface and think you’ve done that now – dig deeper and explore all the possibilities. After 30 or more years of stitching, I feel like I still have things to learn and explore in my little niche.

2 comments

Anita Charlton

I have just been to a talk/lecture with Tanya Bentham. Utterly entertaining, inspiring and historic; we all had a fun afternoon. I’m looking forward to trying Laid and Couched work with her next month.

jean battle

I am planning talks for Newbury creative Stitchers and would love to know if Tanya Benham would come and talk to the group in 2025 ?