They say, ‘necessity is the mother of invention’. And evidently, as you will soon discover, necessity can also birth a textile art vocation.

As a young art student in the 90’s, Emma Cassi fell in love with fashion designer Dries Van Noten’s intricate and colourful embroidered scarves. Her student budget, however, offered no hope of ownership, so Emma tried to create her own scarf. That experiment would set Emma on a textile art journey for years to come.

Emma has a passion for working with what’s on hand, describing it as both an inventive and resourceful approach to making. She also loves the ‘alchemy’ of creating her own dyes from her natural surroundings. Who knew red mud could create such magical textures and colours?

We’re excited to share Emma’s diverse portfolio that’s aesthetically and spiritually connected. Emma literally lives and breathes her creative process, and it’s a wonderful reminder of how the process is as valuable as the end result.

It started with a scarf

Emma Cassi: My mum was a fine seamstress, and both of my grandmothers were incredible with needles and textiles. One of my grandmothers spent her time crocheting in her armchair, and the other repaired garments and socks to perfection.

I completed a year of Art History at university and then enrolled in the Beaux-Arts in Dijon, France. I didn’t work with textiles for my coursework, but I started embroidering in my spare time. It was like a hobby, and I was very bad at it in the beginning.

While studying, I attended Ann Hamilton’s solo exhibition in Lyon (1997) where I had a big revelation. A peacock was running free in a room with floating red fabric hung across the ceiling, and big, white textile panels with embroidered poems hung from the ceiling to the floor. It was the first conceptual textile art I had seen. It touched me because it was poetic, beautiful, and so unusual.

At the same time, Dries Van Noten was using embroidery from India in his designs. Art and fashion were mixing, and it was a very interesting time. Embroidery wasn’t as fashionable in 1996 – it was either in museums or in grannies’ wardrobes.

Van Noten’s use of delicate beadwork, stunning mixes of colors and patterns were exquisite. His designs and collaboration with the best artisans in the world made him one of the best fashion designers.

Of course, I couldn’t afford any of Van Noten’s scarves, so I tried making them myself. That was the beginning of a 20-year training endeavour and my relationship with fabric, needles and threads.

Vegetal alchemy

My connection to alchemy began by chance at the Wellcome Collection Library where I assisted with the translation of an old alchemical book written in French. At the time, I was studying herbalism, and I was captivated by the art of ‘spagery’ – transforming plants into medicinal essences.

Rudolf Steiner’s Alchemy of the Everyday further deepened my interest, and in 2018, my curiosity led me to begin dyeing fabrics using herbal infusions.

I work with natural materials such as plants, mud and powders, and I use rainwater or mountain water to allow the elements to influence the outcome. Fabrics are left outside to interact with the sun, wind and rain, creating unpredictable and organic patterns.

The process is as important as the result, embracing imperfection and spontaneity. I never repeat the same mixture or method, which makes each piece unique. Alchemy and vegetal come to life as a dialogue between materials and elements. Transformation is at the heart of my creations, and the journey is as meaningful as the final work.

“For me, ‘vegetal’ represents the raw, untamed energy of nature. So, my approach to fabric dyeing is wild and intuitive.”

Emma Cassi, Embroidery artist

Avocado skins & berries

I love using avocado skins and pits, turmeric powder, and berries I find in nature, such as blackberries. Pomegranate skins and leaves also play a big role in my dyeing process. The plants I choose often reflect where I am. For example, when I lived in England, I worked with nettles. Now in Spain, rosemary has become a staple.

Bundle dyeing is one of my favourite techniques. It’s such a joyful process, where petals, flowers, leaves and anything found in nature comes together to create unique, unpredictable patterns.

“The magic lies in the transformation – ordinary materials become vibrant colours, often in surprising ways.”

Emma Cassi, Embroidery artist

Flea market treasures

I often visit the vibrant El Rastro Sunday morning flea market in Madrid, Spain. It’s a wonderful place to uncover unique treasures and fabrics. However, I still have a deep connection to the flea markets and brocantes in my hometown of Dijon, France, to source vintage materials.

I’ve been collecting a lot of linen lately to make curtains. I then repurpose leftover pieces for other projects. I also recently came across a beautiful collection of vintage handkerchiefs that I’m transforming with embroidery.

Upcycled cotton bed linens with holes or stains are also appealing. I enjoy their well-worn softness and am inspired by the fact they’ve been washed countless times. I’m giving them a second life, breathing new stories into materials that witnessed so many dreams.

Vintage threads are also lovely, particularly cotton and silk. They have a unique texture and quality that often tells a story, enhancing the narrative aspect of my pieces.

Occasionally I’ve come across collections of old threads, which feel like little treasures waiting to be revived. They bring a timeless elegance to my stitching, making each piece feel deeply connected to the past.

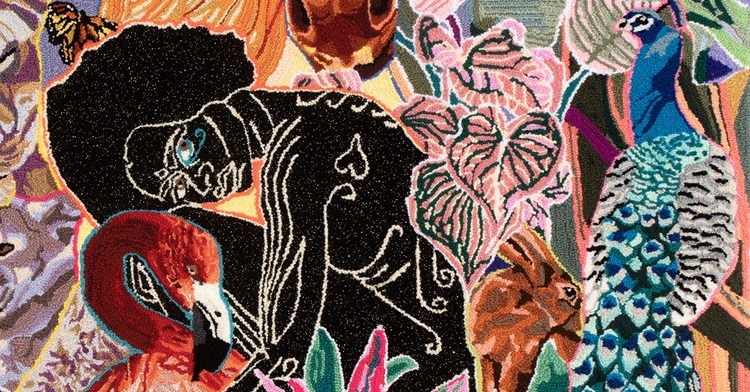

African beadwork

Shortly after designing some masks for Hand & Lock, I travelled to Kenya where I fell in love with the incredible artistry of African beadwork. I saw sacred works including Masai jewellery, Yoruba beaded chains from Nigeria, wire-beaded animals and stunning wall hangings. They were truly magical and left a deep impression on me.

When I returned, I began creating 3D portraits as a way to continue my intimate connection with Kenya’s cultural richness and my passion for beading embroidery.

I had already explored intricate beadwork and sequins in my jewellery-making practice. However, transitioning those techniques to textile art brought new challenges, particularly in creating the 3D effect. I experimented with adding stuffing to specific areas which required a balance between structure and flexibility to ensure it was still easy to embroider upon.

Mastering that method was a huge win, as it opened new possibilities for depth and texture. Seeing how the beadwork transforms a flat surface into something alive and dimensional has been incredibly rewarding.

Beading advice

My advice for readers wanting to add beadwork to their textile art is to start by exploring different types of beads to find what resonates with them, whether it’s their textures, colours or materials. It’s good to experiment with various sizes to see what looks best or feels most natural.

Beading is a tactile and intuitive process, so take time to play, experiment and let your creativity guide you. Don’t be afraid to mix materials or create your own techniques. There’s no right or wrong way to incorporate beads into your art.

In my Stitch Club workshop, I share my tips and ideas so that members can create a captivating 3D portrait inspired by African beading traditions. By mixing trapunto and intricate beadwork they can form unusual and striking faces with 3D, contoured elements.

I hope students embrace the joy of intuitive creation and see the transformative power of blending materials. More importantly, I want them to experience the magic of creating something deeply personal and see how each step in the journey is as meaningful as the finished piece.

Wearable embroidery

My garment named Seedling was inspired by a friend and our shared connection to the Cistus plant, which is sometimes called rockrose. We first met because of that plant: she had it in a vase in her studio, and I immediately recognized its amazing wild scent and told her it was my favourite.

That conversation not only sparked a friendship, but also a jewellery collaboration, and later, a performance featuring this kimono and skirt.

I wrote a poem for my friend, that blended the story of the rockrose with our own journey and I stitched the poem into the garment. The garment’s colors were inspired by a cave in the countryside where she wore it during our performance.

I dyed recycled cotton bed linen with mud, indigo and henna. The embroidery was done outdoors during the summer to capture the essence of nature’s textures and spirit. The piece symbolizes a deep intertwining friendship, memory and the natural world.

Mud dyeing

This body of work is deeply inspired by my life in the hills of the Valencia region, where I embrace a way of living that is closely connected to nature. Every day I walk through the wild landscapes, bathe in and drink fresh water from the mountains and live without electricity or the internet.

When we moved to Spain, we bought a house dating back to 1900. In the barn, I discovered an old, stained canvas which became the foundation for this series. I began experimenting with dyeing and printing using the red mud from the land surrounding the house.

I had been searching for a nude or pinkish tone for my dyework. When I noticed the stunning dark red and brownish mud in the Spanish landscape, I decided to dig a bit and experiment with dyeing fabric. To my delight, it worked beautifully.

I hang the canvases in the attic and let buckets of fabric and red mud macerate for months. This slow natural process allows the materials to transform over time, creating unique textures and patterns that reflect the essence of the place and its rhythm.

“Dyeing with mud allows me to connect deeply with the place, transforming a forgotten material into something meaningful and alive with the spirit of its origins.”

Emma Cassi, Embroidery artist

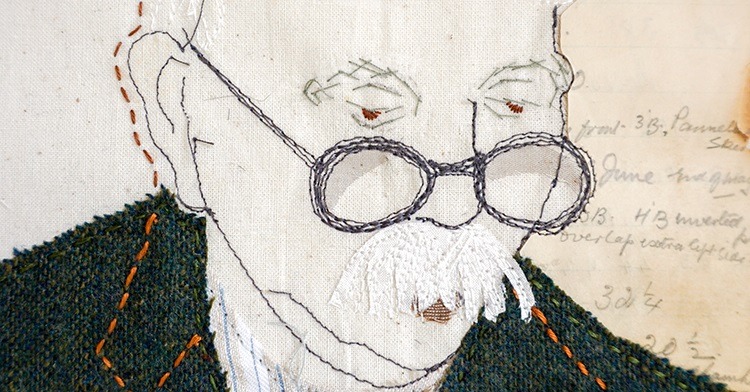

Meditative silk landscapes

After injuring myself from years of intensive embroidery on lace for jewellery, I had to pause and step away. These silk panels became my way back to embroidery. Working with silk provided a healing framework by allowing me to use my needle on the soft, delicate fabric without straining my shoulder. I was able to reconnect with my craft gradually and gently.

The silk panels offer a beautiful canvas on which to explore embroidery and colour. I used vintage threads, combining silk, cotton and fine wool to create layers of texture and richness. The process is deeply meditative, and the softness and thinness of the fabric demand patience and care.

Over the past six years, this practice has evolved into an integral part of my creative journey, merging healing and artistry.

The new gold

I love how I can transform everyday materials into jewellery that is both precious and meaningful. The collection I created for the Seedling project felt like an exciting and effervescent process – it came together over just a few months.

I embroidered hundreds of seeds collected from making butternut and pumpkin soup every day. The variety of shades and shapes inspired me. I dyed the silk with henna, turmeric and indigo which created a rich, textured finish.

I think the collection showcases a rare blend of Edwardian elegance and ethnic aesthetics. Each piece has been thoughtfully crafted to evoke the essence of ritualistic objects, embodying the spirit of talismans imbued with meaning and artistry.

People also resonated with the story behind the seeds as being ‘the new gold’. Wearing the embroidered seeds and regarding them as something precious became a beautiful metaphor for valuing the legend of the fertility deity named Kokopelli, as well as bringing attention to a seed saving project that inspired the collection.

7 comments

Jean Davis

I love the piece “Alchimie Vegetale”! The way the cloth takes the dye is very beautiful.

Siân Goff

It’s beautiful, isn’t it? I love Emma’s inventive ways of working with natural dyes. Thank you for your comment!

christine klein

What a fabulous inspirational article. Have just done a basket weaving course so now inspired to get out fabrics I won’t use and turn into baskets. Your work is lovely

Patty Pittala

Beautiful article, beautiful work. I can relate to her thought process with creating. I also felt her sense of ‘play’ when in the creative project. She seems comfortable in her visions- that’s refreshing!

Barbara

This article is a delight. I enjoyed following Emma Cassi’s progression and her response to what inspired her. I wonder if the caption on one photo should read Delica japanese beads and not delicate … I use them too. I love the distinctive matte finish.

Mary Moffat

Love your bowls I have made many bowls in felt and you have inspired me to try more open topped bowls

rose

what interesting installations,i admire your creative and adventurous spirit.