Are you one of those textile artists who has constant creative epiphanies? When one artwork is complete, the muse magically appears to deliver a fully formed concept or design for the next.

And does that ‘divine intervention’ stay strong and true as you sail through the making process? As you effortlessly hit upon innovative ways to speak through your techniques and materials. The finished piece fulfilling every detail of your original artistic vision.

No?

Maybe that’s because those ‘super hero’ textile artists don’t exist!

Sure, once in a while going from conception to completion can feel like a stroll in the park. But even the most inventive practitioners, the ones with rich and unique visual identities, hit challenges and problems along the creative path.

And that’s where sampling come in…

What is a sample?

A practice piece. A textile sketch. A stitch journal.

All different ways of describing an experiment in fibre. Or, as it is most commonly referred to, a sample.

Samples can be used as a systematic way of pushing the boundaries of textile techniques. Or on a more ad hoc basis as a way of asking ‘what if?’ to test out ideas for a specific piece.

There is no right or wrong approach. But what we’ve learned from interviewing over 500 inspirational creatives here at TextileArtist.org, is that making samples can be invaluable in developing work that transcends imitation and repetition.

5 Sampling super powers

1. Winning with a warm-up

If you long to feed your passion for working with textiles but the thought of jumping straight into making a full piece feels overwhelming, you have two options.

- Let the overwhelm win and make nothing.

- Get started by making something small, manageable and fun.

Making a sample or two can be a great way of getting over that initial anxiety because you’re starting with a mini-project that feels achievable. There’s nothing scary about a sample!

2. Powering through perfectionism

The number one cause of artistic paralysis is fear. Fear of not being good enough. Which leads to perfectionism. Which leads to fear of taking a risk. Which leads to fear of creating anything at all. It’s an endless cycle until you break it.

Sampling empowers you to get creative without fear.

The pressure is low. Making samples won’t take up lots of time and the results can remain private and personal if you so choose.

So, you’re free to fail. And remember, failure is only failure if you don’t learn and progress. Analysing your samples can help you do just that.

3. Itching with inspiration

I truly love writing these articles for TextileArtist.org, but I always know when I haven’t done enough groundwork or research. Because I feel uninspired. The words won’t come. The whole process feels clunky.

And it’s frustrating because I’m writing about a subject I have a passion for. But passion is not enough. I need the relevant information at my fingertips, a premise from which to start and a structure to give me a clear path forward.

Making textile art isn’t that different. Experiments in stitch and mixed media are your groundwork. They can offer up a wonderful starting point for new projects. Or become stepping stones for larger ones. Or even small works of art in their own right.

Samples can fuel the creative process.

4. Searching for solutions

Ever hit a roadblock in middle of making a new piece and had no idea how to get around it? Not having a system in place for finding solutions can lead to piles and piles of half-finished work.

Think of sampling as a way to try out techniques. To audition fabrics, colours and textures. To make decisions and solve problems, both at the beginning of your process or when you’re in the trenches.

Sampling can get you round those inevitable road blocks.

5. Evading imitation

How do you build an original and clear visual identity? Embracing the influence of other artists can spark ideas. But taking those ideas and making them your own is another challenge entirely.

Concepts need development and techniques require ownership. Otherwise you may find yourself falling back on imitation.

Creating samples is the perfect way to push boundaries, become more inventive and explore how to do things your own way.

And taking what you discover in one experiment forward by developing in the next, means your voice will evolve and your confidence in it will grow.

How 6 textile artists use sampling in their process

We asked 6 very different but equally brilliant textile artists to share their sampling processes with us.

Carol Howard Donati

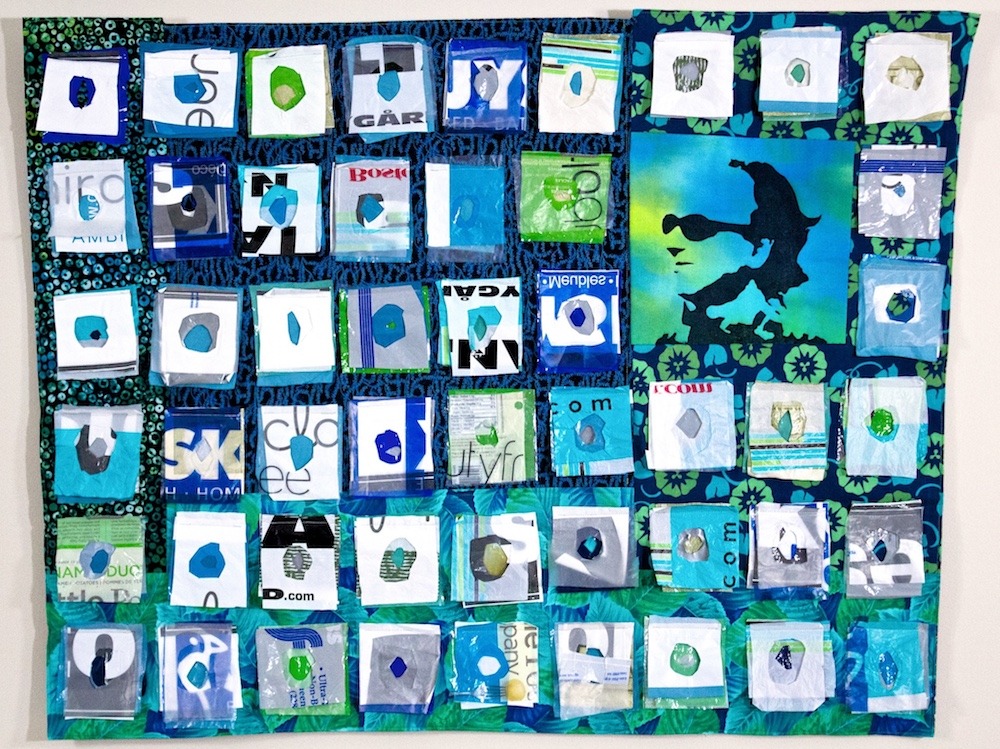

Canadian artist Carol Howard Donati works with fabric, paint, thread and recycled domestic materials. Her work draws from several themes; her background in anthropology, her appreciation of the traditions of hand stitching, and her fascination with materials and design ideas taken from everyday life.

Carol Howard Donati: As a mixed media artist, creating informal scrap samples is part of my ongoing, stream-of-conscious process of working with a variety of different materials.

A sample is often the first step for me in taking an idea to the next level. One frequently leads to another in a series of explorations, especially when working with novel materials. I create samples to find out what a material can do, how it handles, or how it might combine with something else.

I also make samples as part of problem solving for an artwork already underway. I will test an over-print, stitch pattern, or edge finishing on smaller fabric to assess adjustments in advance of committing them to the main piece.

The majority of my samples are quick studies made with scraps that usually find their way to the studio floor. Only a fraction are saved in my sketchbook. In some cases, after it is made, I think of a finished artwork as a sample for the next piece I imagine.

Exploring an idea

I was introduced to the concept of decellularisation during a Biology and Art Residency I took with Ayatana in Gatineau, Quebec.

Decellularisation is one step in a novel process invented at the Andrew Pelling Institute for Biophysical Manipulation that reduces organic material to its cellular scaffolding so the structure can be used as a foundation for growing new cells. The potential of this discovery, and its associations with recycling and regeneration, fascinates me.

Inspired to make my own cell units, I experimented with several versions of layered plastic held together with a line of stitch. To represent decellularisation, I trialled ways of removing the central part of the cells.

I like the crusted irregularity of melting plastic away with heat, but in the end chose to clip back layers separately using scissors. The cell units were the inspiration for creating Natural World, their final form simplified to integrate with appearing in multiples in the larger composition.

I mounted cells in rows across an irregularly-shaped, pieced background, and included a screen-printed human face in the final design. To emphasise texture and dimension, and take advantage of the shadowing from misaligned holes in the centre of the cells, I secured the units by their top edge only allowing the layers of plastic to stand free.

The result is a dynamic, dimensional surface, subtly alive through its ability to respond to air movement.

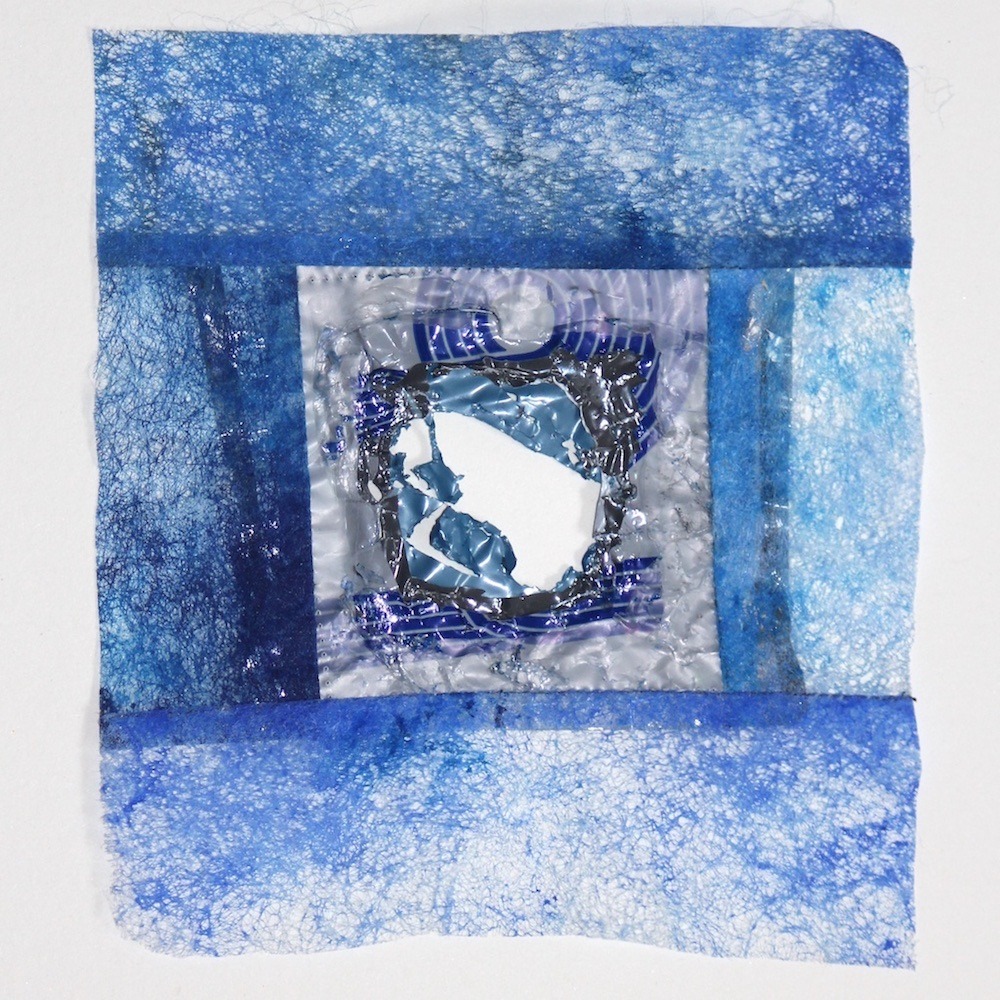

Dynamic overprinting

When I first completed Where have all the mothers gone? I was dissatisfied with the static energy of the piece and wondered what I could do to improve it. I felt I had missed conveying the dynamic aspect of the AIDS epidemic and how it was decimating women of childbearing years in sub-Saharan Africa.

The pattern of white plastic milk and bread ties between squares of African fabrics on the surface of the piece was my way of making the connection between women, nurture, and sustenance, as well as implying the treatment of women as trivial, disposal objects. What about the ongoing social, cultural and economic ramifications?

I decided to overprint the entire piece with concentric, expanding rings to represent the ripple effect of AIDS impacting women. I frequently use a shell shape in my art as a female symbol. This time I chose to print the outline of a cowrie shell, recognized in many African cultures as a feminine form.

To solve the technical difficulties of printing on a textured surface, and to achieve just the desired texture and opacity of paint, I took my three sizes of shell shapes and test printed them on samples of the background silk.

To gauge the best colour, I trialled both red and white paint – both having associations with death and the feminine – and eventually chose white for its visual impact, and its echo of the white colour of the plastic tags. Making sample prints on scrap fabric reduced my risk of error and helped me to achieve the dynamic pattern I envisioned across the surface of my finished work.

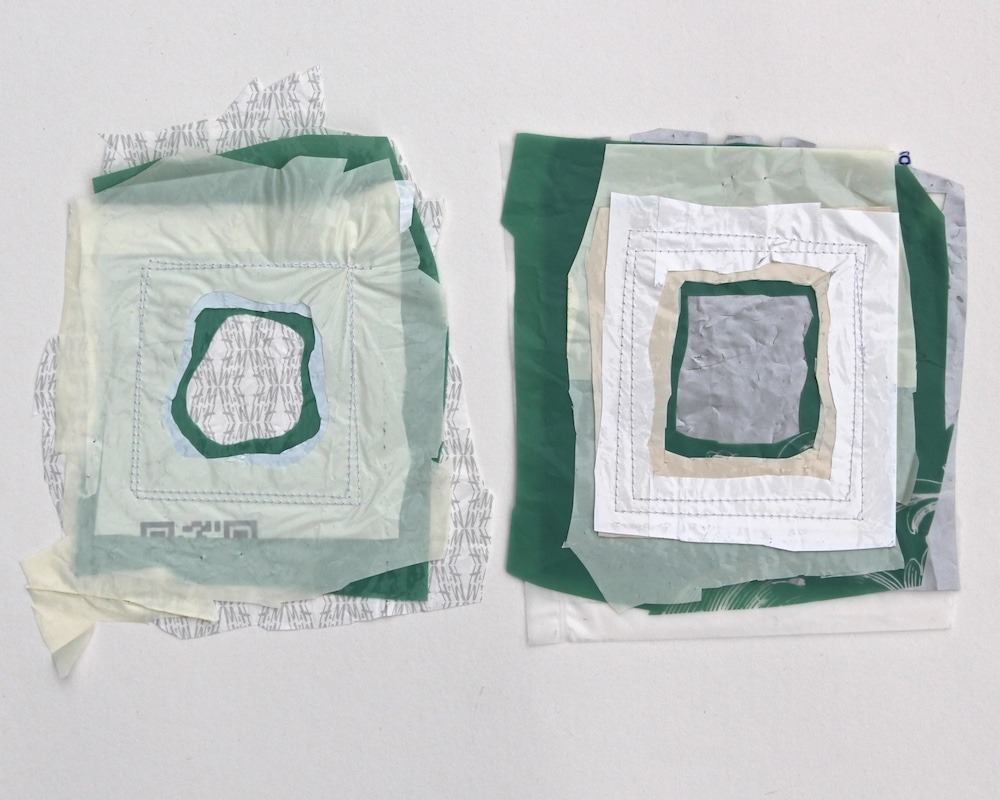

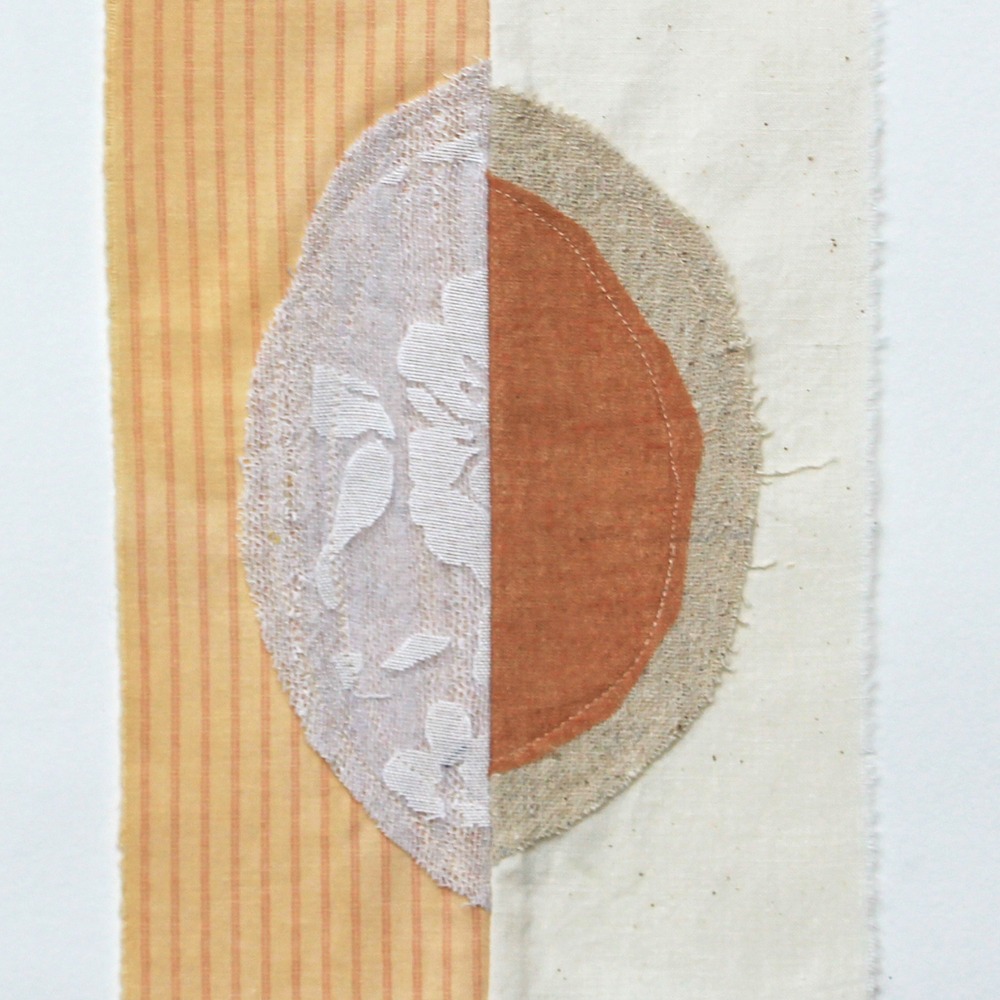

Mixing this with that

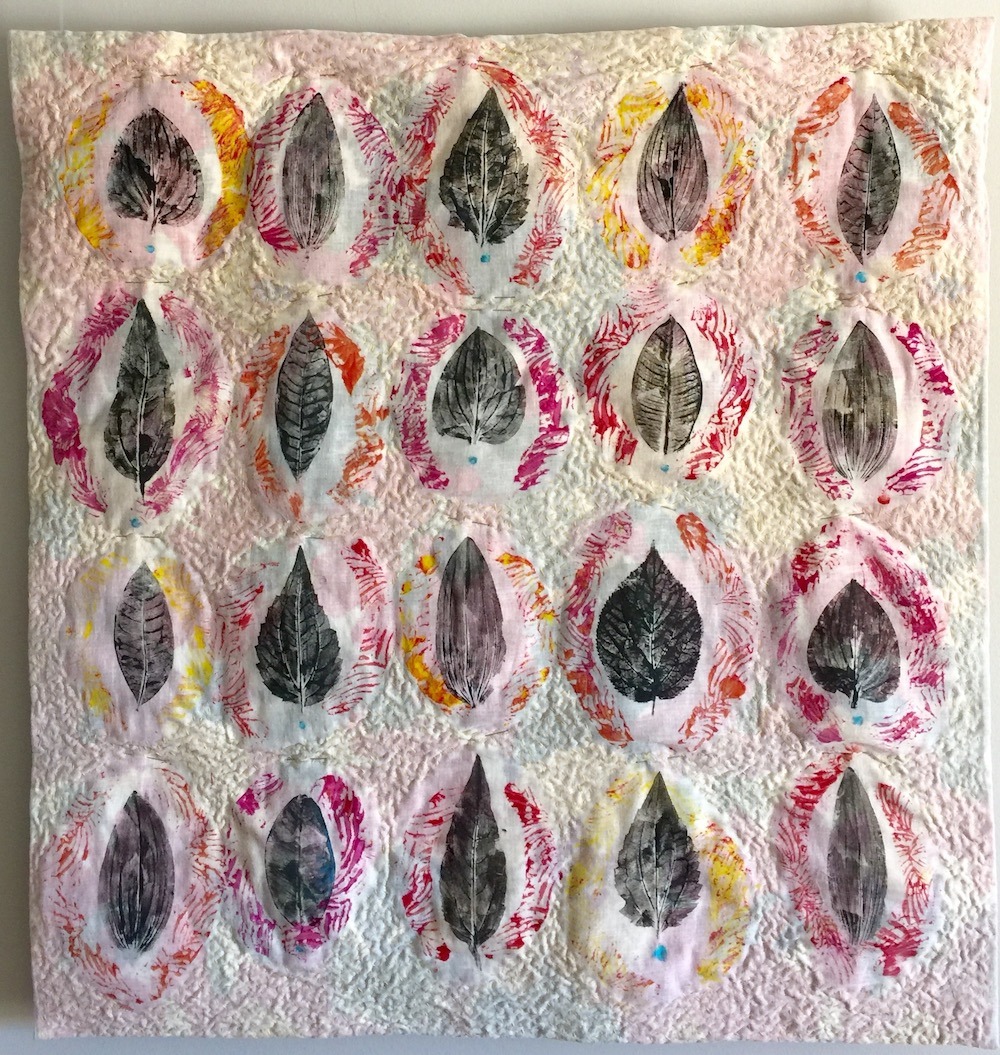

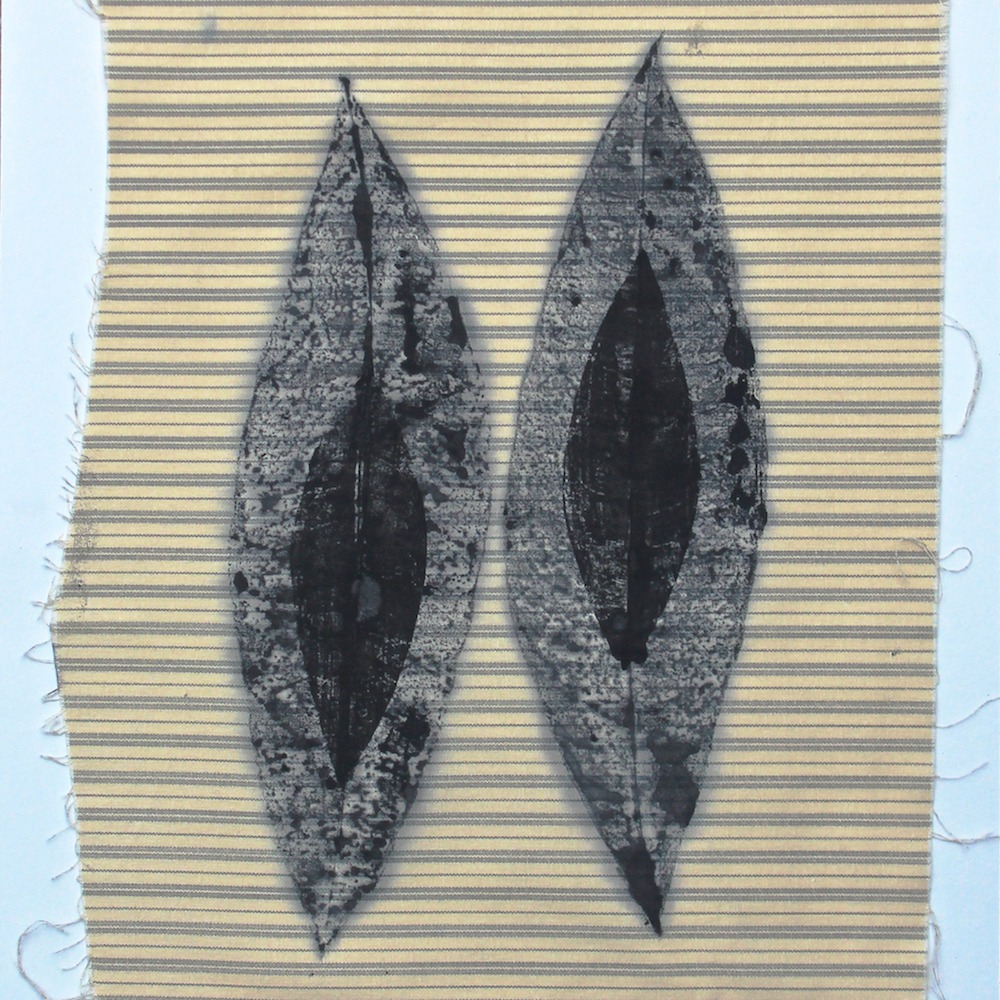

I have a habit of including circles, ovals, shell shapes, and apertures of various kinds in my artwork. I relate generally to the ovoid form as feminine, and repeat it as a personal and universal symbol in things I create. Over the last few years, in recognition of the amount of time I enjoy spending outside in nature, I have added the leaf shape to my visual art vocabulary.

The focus of my latest work is self and landscape. Bringing back leaves from morning walks down by the river has led to experiments with making direct prints with inked leaves on fabric. Combining this with that: ideas from several kinds of sample work – stitched ovals, dimensional ovals, and leaf prints – became the inspiration for Hidden Self.

Hidden Self is a whole cloth, hand stitched piece made with two layers: a sheer light layer over a heavier floral upholstery fabric. The sheer is hand printed with leaves from the forest and each leaf is embraced by a set of coloured brackets printed from a template made from textured wallpaper.

Asymmetrical handling between the two layers, and between areas of dense hand stitching and areas of no stitching results in a softly dimensional effect where the leaf printed areas stand slightly forward from a puckered ground.

Website: carolhowarddonati.ca

Cos Ahmet

Cos Ahmet has a BA Honours in Constructed Textiles from Middlesex University. He takes the traditional and practical methods of weaving and uses them to create thought provoking works, exploring themes of self, identity, sexuality, gender and memory. As you will find out, Cos often uses a cast of his own face as part of his artwork.

Immersed in ‘play’

Cos Ahmet: Apart from recording my ideas in sketchbook form, and gathering inspiration from a number of sources, I also document through experiments. Samples are the testing ground to see if an idea will actually work.

Sometimes an idea goes through weaving, printmaking/collage or object form to find where it will best sit.

I rather enjoy this process and sometimes find it more exciting than making the finished article. You become immersed in the ‘play’ with materials and come across things that you never had in mind.

For me, many of the samples I create never make it any further than that initial stage. Some become ‘small works’ in their own right. The ones that don’t tend to serve as inspirations for other ideas or projects. Or maybe they’re never revisited, and that’s okay. It is part of the process.

Seeking an energy

Occasionally, samples that I am working on become the actual piece, or at least a component. This doesn’t happen all the time, so when it does, it is because the sample has the energy or ‘feel’ I was after.

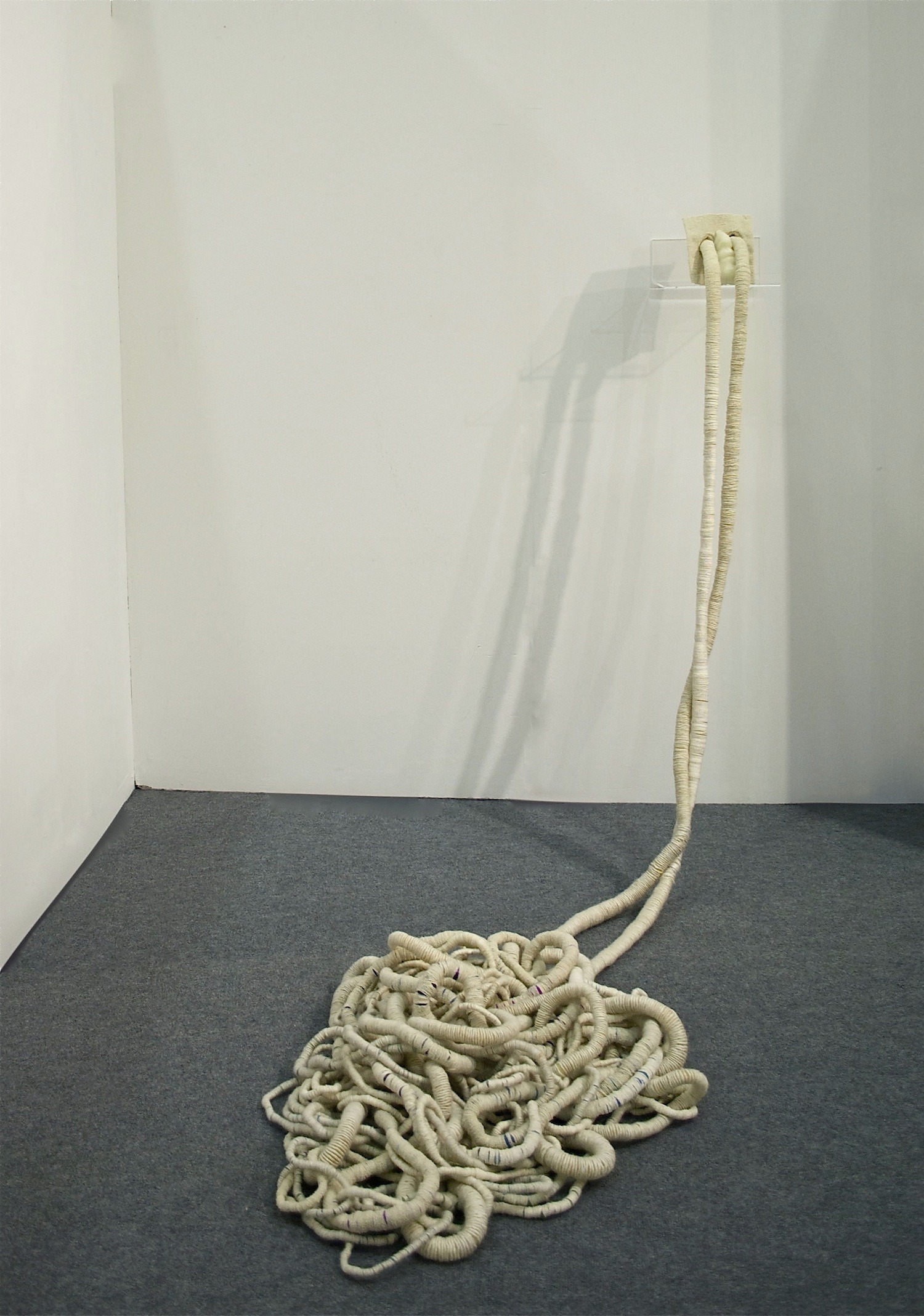

A case in mind is a recent work called My Tears Form Structure.

I didn’t have a specific look for this work, but wanted to have a feature that referred to the face. Initially, it was going to be a woven structure with eyeholes, with wrapped cords trailing from them. The sample I created was just perfect, so I ended up using it.

After attaching the structure to the cords, I felt something was missing, so went on experimenting in other materials to find the best way of making a cast of my face. The combination of woven and cast wax structure, gives a great contrast.

Testing testing

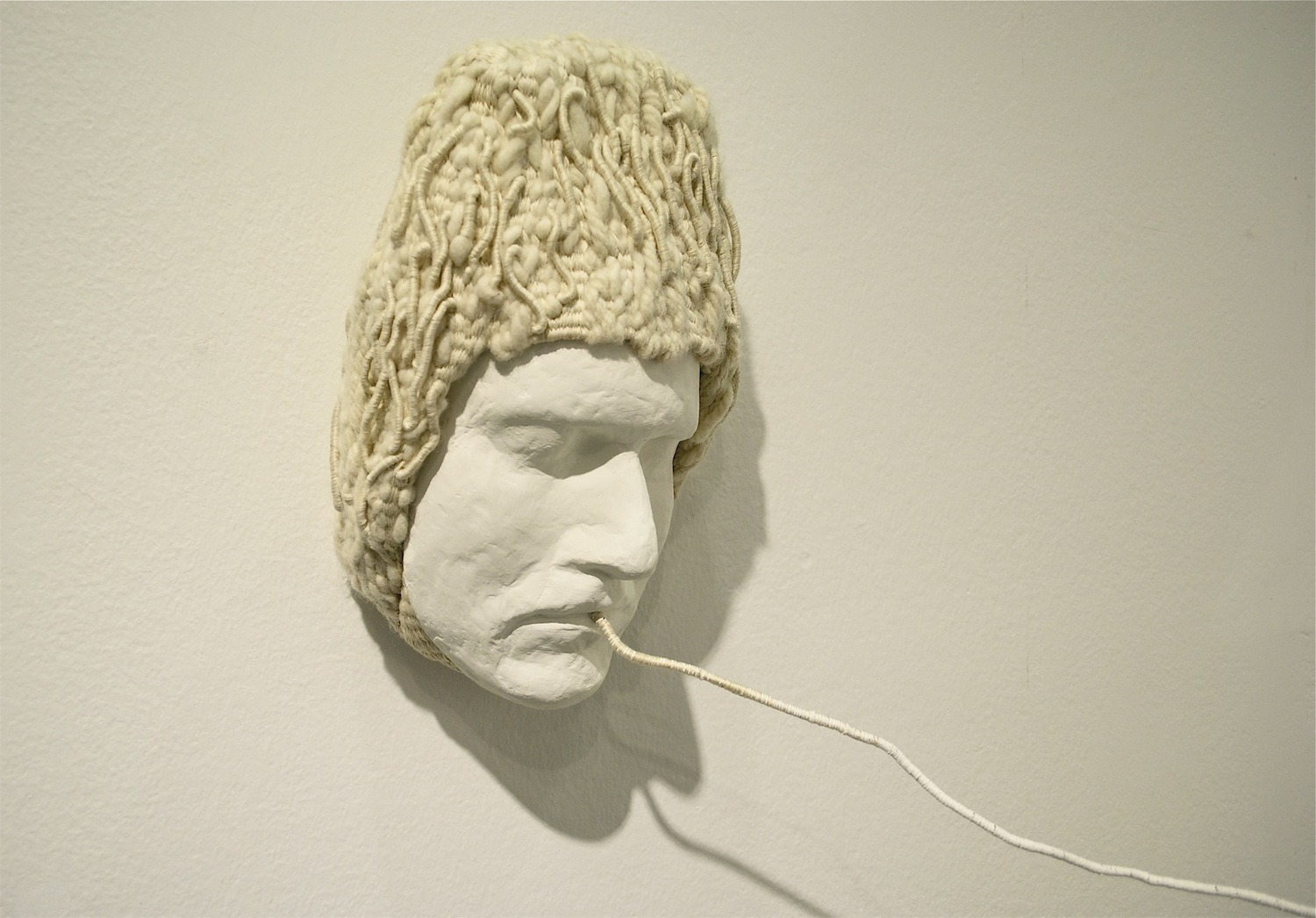

Samples that have developed and changed from the testing stage into a finished piece are evident in my work Drawboy. Once again the mask (a cast of my face) has entered the work, with the woven element becoming an almost outer brain, with a writhing worm-like texture.

The texture has no specific place of inspiration, but is a combination of influences that hint at the bodily; internal or organ-like.

Tests for this and other elements to the piece were explored through my use of casting, seen in the array of masks, and the sampling of weaving techniques.

The woven tapestry technique I used is known as ‘wrapping’ or ‘whipping’. The woven side to this piece went further than the sample I made. Change of yarns and thickness gives it more body and movement, but stays true to the texture achieved in the sample.

The final part to this piece is the thread that is being pulled from the mouth. Tests I made for this ranged from woven mouths, and threads/cords from wax casts. The white, paper and plaster-resin mask proved to work the best in this case.

Website: cosahmet.co.uk

Read TextileArtist.org’s interview with Cos here

Monica Bennett

Monica Bennett is a member of the international Surface Design Association, Craft Council of British Columbia and the Southern Gulf Islands Arts Council and has worked with handmade felt since 2001.

Sampling gives me confidence

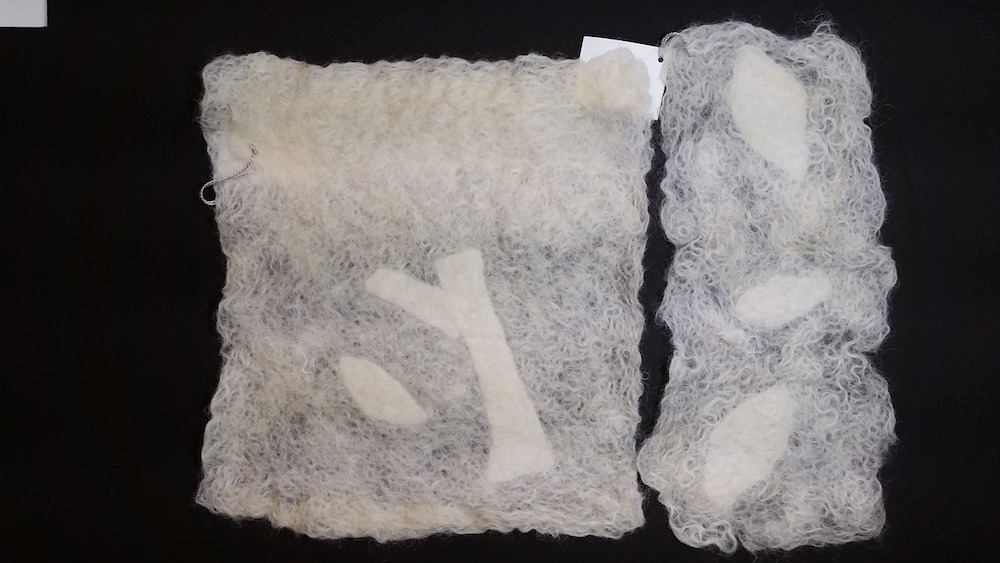

Monica Bennett: As a felt artist, I wet felt all my pieces by hand, so I want to be certain that I’m not going to waste my efforts. Making samples helps me think through ideas, work out technical issues, test fibres and try new techniques.

When I first started in the textile arts, I felt a bit guilty about ‘wasting time and supplies’ by making samples. But I have learned that samples actually save me time and materials. I can see if the results match my vision. If they don’t, I can change fibres, adjust techniques or alter my vision before committing to the final piece.

For every sample, I make notes on materials, layout, measurements, techniques, the end results and any possible changes. All samples have tags with fibres used and the date for easy reference. Being organised helps me remember how and why I created a certain piece.

Samples give me the confidence to tackle larger or more intricate pieces because I can try out a concept or thought beforehand and see how and where I could develop it.

Gaining clarity

Recently, I’ve been working with the effects of light shining through felt. For Arbutus (a custom made room screen with hand felted panels made from Cotswold sheep locks and Merino prefelt) I teased out each lock by hand, removing all vegetable matter, until there were bags and bags of fluffy locks.

The two finished panels had to measure just under 150cm x 60cm, the tree pattern had to line up at the middle and all 8 crossbar pockets had to match up. I needed samples.

Felted carded locks vs hand teased samples showed me the difference in the locks’ integrity and shrinkage, as you can see in Sample A. Sample B made it easy to decide on placing the prefelt in between the locks vs on top.

Finally, I felted up a pocket rod resist sample to check shrinkage. Having these samples helped calm some of the nerves and allowed me to get clear about the look of the piece before I laid out the first panel and got started.

Saving time

Rock Forms showcases some of my favourite techniques sampled recently.

Before starting the piece, I made a sample using the fibres and layout I had planned. To be a bit more efficient I put all three on one base.

Good thing I had tested out a few thoughts.

First off, I didn’t like the grey Finn wool base so I changed it to black.

Second, I had forgotten to pleat the silk chiffon so didn’t get the result I was looking for.

Thirdly, I tested the carved felt ridges to estimate wool depth and shrinkage. Cutting into one’s finished work can be stressful so it’s great to cut up a sample first.

Finally, I tried some black wool under part of cream and grey wools in the cracked stone section, envisioning the outline it would give to the cut edges. As it turned out, I much preferred the clean look of the area without the black wool.

The samples confirmed the direction I wanted to go, reminded me of correct layouts and saved guess-work on the final piece.

Website: monicabennet.ca

Adam Pritchett

Adam Pritchett has a BA(Hons) in Fine Arts from Coventry University and sells his work on Etsy as The Old Needle.

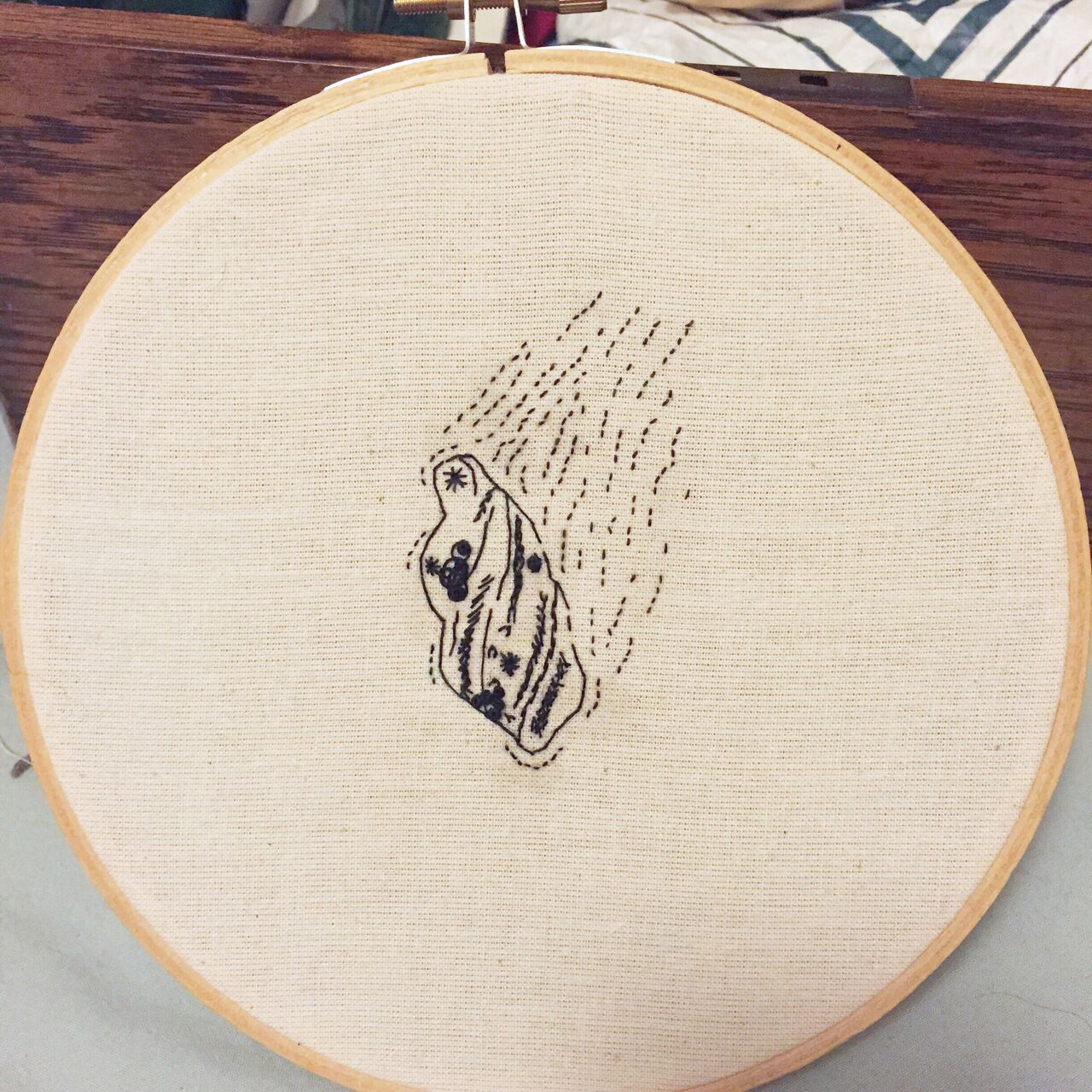

Adam Pritchett: Being self taught in my practice, most of my knowledge is from books and examples found from various sources, so for me making samples has always been such a useful tool in not only testing out a new technique but also in beginning to experiment.

I used to keep extensive sketchbooks while at university solely devoted to testing fabric dyes, appliqué, weaving, felting — sadly they’re all buried in an attic somewhere.

I now tend to make small samples to try an idea before starting a full piece of work.

I also dye a lot of my own fabric so test batches and fabric samplers are key when experimenting with colour palettes.

I frequently use test pieces to experiment with varieties of stitches and thread types, making a number of small embroideries, that I then base full pieces of work on at a later stage. I keep these small experiments for reference to reflect back on later.

Working in this way, I’ve discovered many different ways of manipulating the thread to give different textures and line effects, that I’ve then gone on to use again and again.

I created a smocking texture sample after seeing another textile artist recommend an antique pattern she had found; I just had to test it out. After making this small sample, I made a larger version on a linen fabric that eventually became the background texture for a piece of work called Wandering Mystic that travelled to a gallery show in the US.

I made one of my earliest embroidery samples using dozens of old stitch demonstration books and pictograms I had found online. Not one of my finest works, but this piece was the catalyst for all of my later experiments with needlework, and eventually led me to where I am now. That for me, makes it one of my most important samplers despite being so small and primitive.

Website: apritchett.co.uk

Robi Szalay

Robin Szalay is a contemporary textile artist based in Australia, primarily concerned with deconstructed cloth, embroidery, hand distressing and print. She is a two-time winner of the Melville Art Award (Textiles category) and three-time winner of the WA Smales Fashion Design Award (Evening wear category).

Robi Szalay: Through my mediums, I hope to evoke a sense of the tactile; an alternate and expansive communication to the spoken word.

Making samples began as a way of exploring different mark making and textile techniques, but quickly built up an enduring and unique visual language for me.

While my work doesn’t always begin with samples, they will still inform my work in some way. Reflecting on past samples often brings me back to a place of authenticity, reminding me of what works and what feels overdone or forced. Knowing when to stop can be a challenge at times so samples can help work through this and ensure I don’t get too precious, meaning I can be more free and open.

There are a number of ways that I utilise samples in my practice and they sometimes become resolved works in their own right.

However, often photographing them captures a sensibility that is more successful than the original piece, playing with focus and depth of field. Transferring a photographed or scanned sample onto a silk screen is another process; sometimes working back into the screen print later.

Then my work with fashion helps me develop ideas in a more playful way. I really enjoy including samples to upcycle, mend or alter existing garments.

It was after creating samples in a Bojagi workshop with Korean Artist & Author Chunghie Lee that I was invited to exhibit in Korea for the now bi-annual Korean Bojagi Forum. Bojagi is a traditional wrapping cloth with beautifully crafted seams and Chunghie invited contemporary responses to this historically significant art form. Being involved with KBF continues to be a very rewarding experience, both culturally and creatively.

Photography takes things to another dimension and forces the viewer to consider the work differently as well as the spaces in between. A mood can be created and the environment controlled unlike the unpredictability of a work in situ. My last series (pictured above) combines the two and offers fertile space for further developments. Working with samples will no doubt bring more experimental options.

Currently I am working on a project with the working title Sew What; an ongoing time based series of small sample pieces which I am documenting and reflecting on with an open outcome. I am looking forward to exhibiting the results some time in the near future.

Visit Robi’s Facebook page here

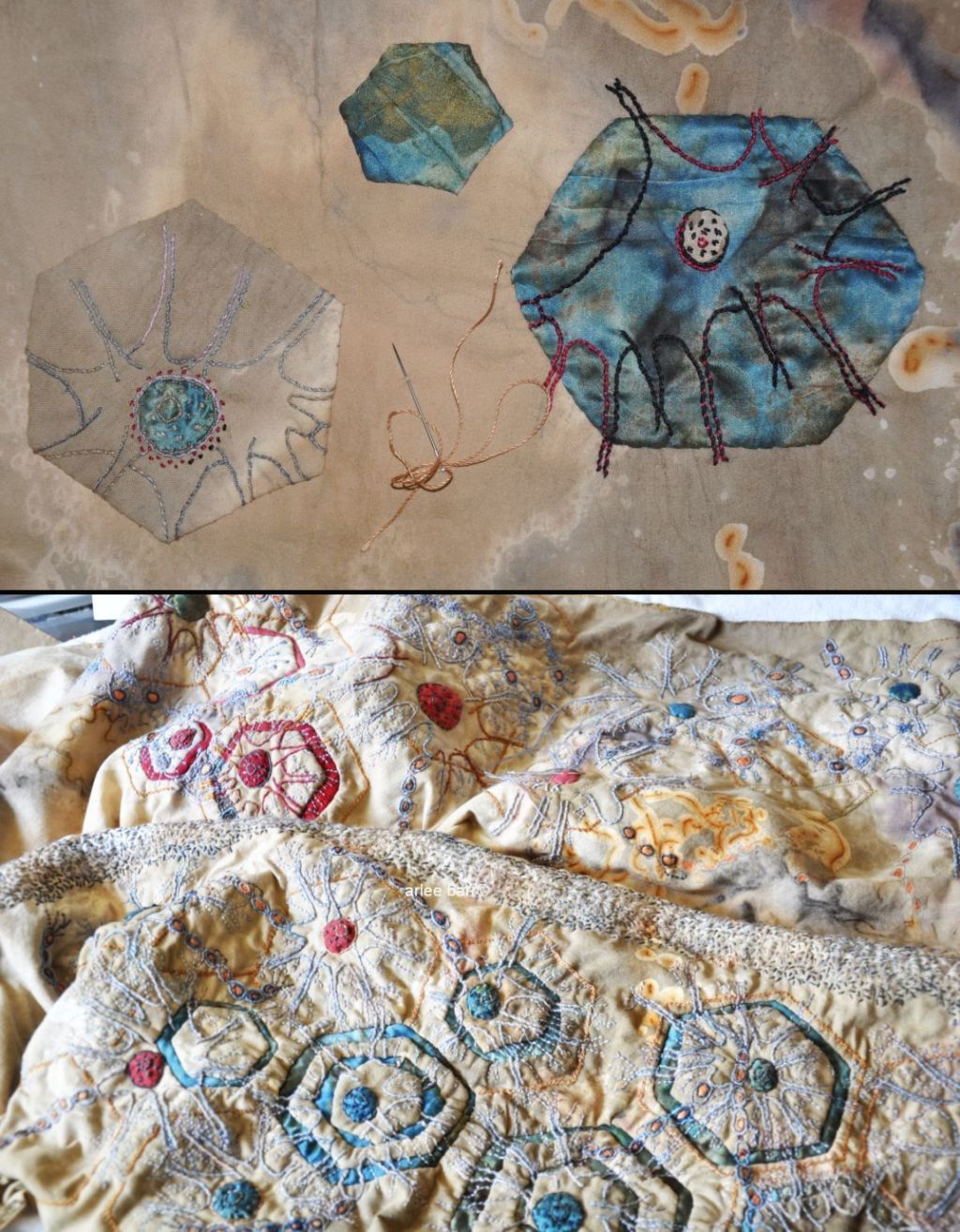

Arlee Barr

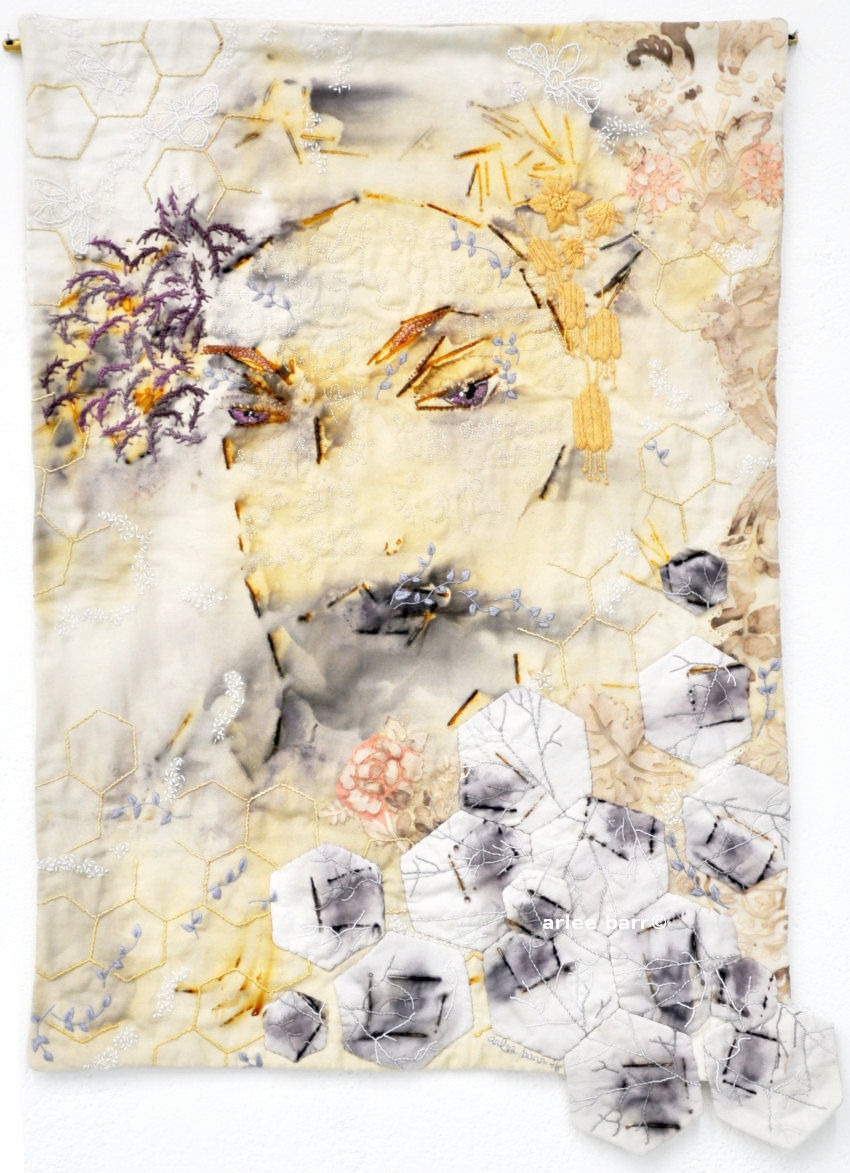

Arlee Barr is a graduate of Capilano College’s Textile Arts programme and has exhibited nationally and internationally. Her focus is combining hand and machine stitch with natural dyeing, in eccentric forms and viewpoints.

A record of your artistic life

Arlee Barr: Time is costly when most of your work is done by hand or with intense machine work. Time spent trying out ideas on samples is constructive. It prevents wasting physical resources, aborted concepts, poorly executed composition, and pointless or extraneous techniques.

Predominantly, I use naturally dyed and rust processed fabrics, which are not replaceable or reproducible. That means it helps to know where the scissors and needles are going to go, and if they are going to translate to what I want to say.

Using scraps of fabrics done with these dye methods means I don’t worry about the preciousness, as I sample different stitches, unique designs, and test scale or a new technique.

Sampling is valuable in that it allows me to experiment, file ideas for future use, toss some in the “round file” and try things I normally may not do.

I used to just jump in blindly, without testing things, but have realised that’s probably why there are more unfinished pieces in my studio than finished!

Sampling is a priceless record of your own style, process, progress and stumbling blocks; a record of your artistic life.

Translating ideas

In A Birth of Silence I was able to sample a technique I wanted to use on rusted fabric using plain cloth first, so I could see if the areas to turn under were too small or too stiff with stitching. This translated well to the rusted fabric, though turning under some edges stiff with iron was a bit problematic.

The practice I had with the sample though, enabled me to add pliers to the scissor/needle mix, and the large sections were completed and applied to the background.

Making decisions

When I started Tabula Memoria, I knew I had to do much more sampling than normal, as it’s a large commissioned piece.

Testing the use of indigo for inclusion allowed me to decide what scale the hexes would be and experiment with the proportion of indigo pieces to the whole. I decided, based on the quick and dirty sample, that the indigo should be a bit more “discrete”, and used it instead as an underlay.

There are also two figures in this piece. The first (not shown in the image) was easy. The standing figure not so much!

I was concerned about appearance, application, technique and colouring.

I first did an A4 sized sample with a scrap of haremcloth, painted and stitched to the background. But I didn’t feel it was working so decided to create the figure with drawn thread work and paint instead. I then applied it after the stitching was done.

I’ve since decided that this figure must be redone anyway; the paint colours feel too heavy, so back to the drawing board (or another sample!).

Website: albedoarlee.com

Read TextileArtist.org’s interview with Arlee Barr here

Do you use sampling in your creative process? Or perhaps you’ve resisted making samples? Get involved in the conversation by leaving us a comment below. We’d love to hear from you.

Comments