The proverb ‘one person’s trash is another person’s treasure’ reigns supreme with these five artists. Each of them rescues neglected and tossed away items to help tell significant truths and stories in their textile art. These artistic hunters and gatherers keep a watchful eye out for overlooked gems and then breathe new life into their found treasures in unexpected ways.

Certainly, there’s a pragmatic satisfaction found in helping the environment by reducing items headed for landfill. But these artists also tap into the joy of imagining the prior lives of their found riches and seamlessly blending the old with the new. Every recycled object bears its own bumps, bruises or sparkle that can’t be purchased or recreated. And that’s where the creative magic of working with secondhand materials lies.

Paul Yore’s works incorporate recycled objects as metaphors addressing the social challenges of queer culture. Louise Baldwin uses salvaged fabrics and construction materials to explore her feelings toward building a new home. Zipporah Camille Thompson celebrates her paternal grandmother through an installation featuring beloved colours and a special rice from the American South. Stacey Chapman builds Her Majesty’s coronation gown from surprising castoffs. And Melissa Emerson portrays a mother’s love on a simple netted fruit bag.

Paul Yore

Paul Yore’s interest in recycled materials initially stemmed from environmental concerns, as well as wanting to pursue a sustainable practice. During his art school days, the free or reduced cost of secondhand goods was also appealing when expensive art materials were out of reach. But Paul’s main driving force in choosing recycled materials connects to queer culture.

‘As a queer artist, my choice in scavenged material centres around an aesthetic of ‘bad-taste’. I’m interested in pop-culture, trash, camp, and lowbrow humour, all qualities which form part of subversive queer culture. I find the conceptual richness of found, thrown-out or waste materials serves as a metaphor for marginality, and by extension, queerness.’

Paul is also motivated by the idea of rescuing pre-loved materials and giving them new life. For example, he uses a lot of secondhand pet blankets with embedded hair. Nothing is off limits in terms of materials and media. Glue and paint may be used to cobble items together, or for tougher materials like plastic, hole punches, eyelets and cable ties work well. Other everyday fibres such as rope, string, fishing line and wire are also used.

Thanks for Nothing features a map of Australia conflated with a skull and the Union Jack flag as the background. Paul says it began as an interrogation of contemporary themes such as nationalism, colonialism, capitalist modes of production, consumerism and the politics of identity through a queer lens. However, the work is quite open-ended and offers a variety of possible interpretations. The work also incorporates diverse words and phrases that are also ripe for interpretation.

‘My interest in found materials extends to using found and borrowed phrases, expressions, slogans, symbols and logos. The layering of those images and sentiments further opens my work as a site for possible critique and speculation. They explore how language informs the ideology that underpins our cultural settings. Interestingly, the words text and textile share an etymological root in the Latin word textere meaning to weave.’

The construction of Thanks for Nothing is essentially a needlepoint embroidery with an appliquéd, quilted border. The wooden frame is embellished with found objects and paint. For the needlepoint section, Paul traced his design onto embroidery canvas and then stitched the main outlines in dark colours. He then slowly covered the rest of the surface with free-form designs, intuitively choosing colours along the way. The border was formed using scraps of off-cuts from larger appliquéd works. After stretching the work onto the frame and fixing it with cable ties, the piece was embellished with hand sewn sequin details and beading.

‘It can be a technical challenge to use materials that vary greatly in their constitution, from coarse materials like denim, jute and thick blankets to fine materials like lace and silk. However, an exciting aspect of my methodology is a sense that things don’t necessarily easily fit together. For me, the variety of degraded or broken-down materials becomes a metaphor for creating a new whole from salvaged parts.’

Paul Yore is based on the unceded land of the Gunaikurnai people in Gippsland, Victoria, Australia. He has exhibited widely, with a major survey exhibition called WORD MADE FLESH (2022) at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, which featured 15 years of work and included over 100 textile pieces.

Instagram: @paul.yore

Louise Baldwin

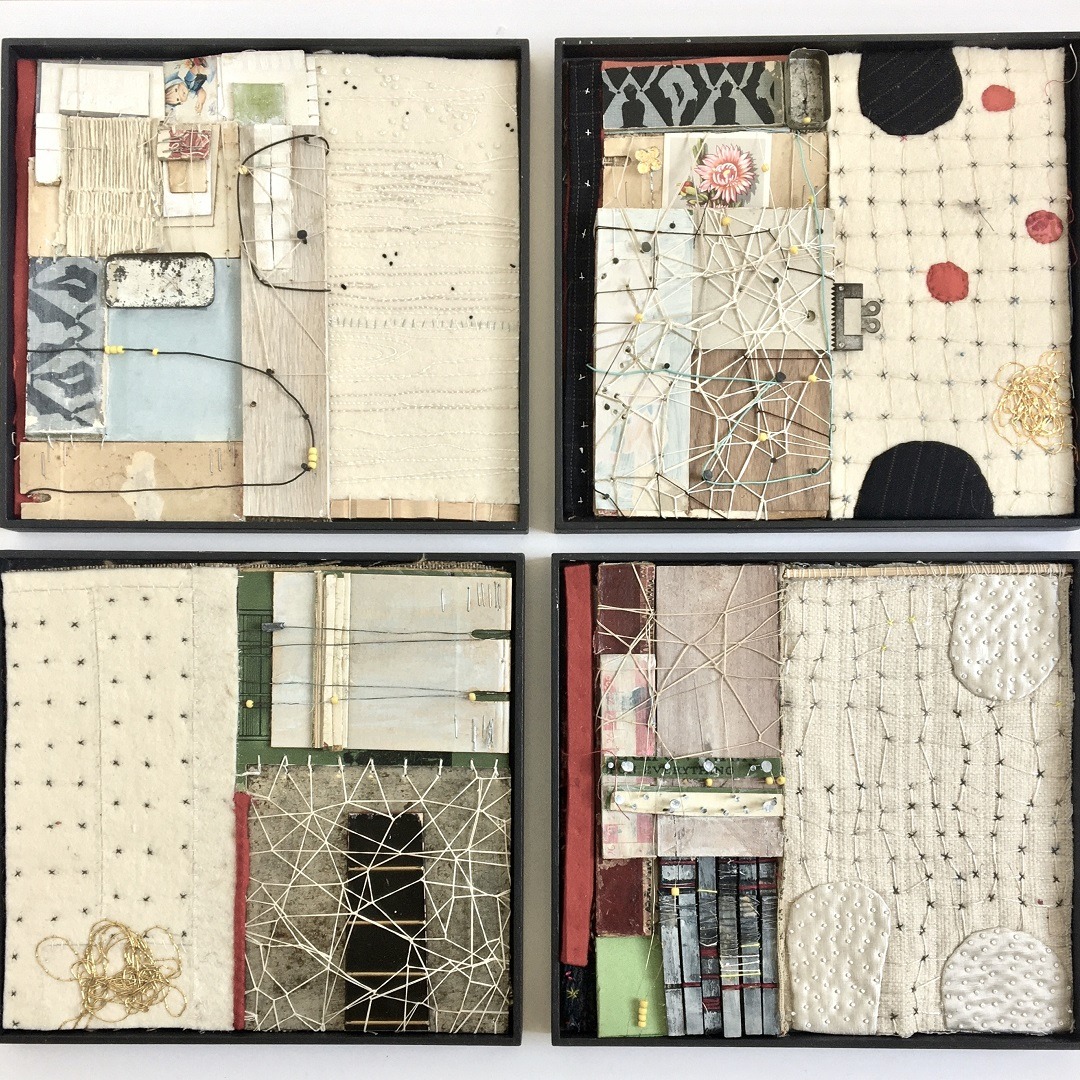

Assemblage art is not for the faint hearted. Juxtaposing disparate elements into a cohesive whole can easily lead to visual chaos. But Louise Baldwin’s ‘bodging’ technique helps her expertly overcome that challenge.

‘My work may appear to take a bish-bash-bosh or that-will-do approach, but in fact, it’s a very slow process squeezing things together and shifting them around, so they work collectively. I like the term bodging to describe the way I combine, mend and repair things. It means using what is to hand rather than going out to find the correct piece of equipment. There is a frugality, inventiveness and accidental beauty to bodging that totally appeals to me.’

Louise admits she also has sentimental attachments to the variety of objects she incorporates into her textile art. She particularly enjoys weathered and handled materials, things that bear a history. Odd things find their way to her collection, from friends’ donated scraps of fabric to items found in London’s plentiful skips to ordinary household packaging. Containers are also of interest, as they often have unexpected details and shapes.

‘I really enjoy the challenge of thinking how materials can come together and have what I call conversations. Materials that have been discarded or lost their original purpose can be transformed and reinvented to take on new meaning. I also always enjoy the lack of hierarchy in the materials I use, treasuring an old plastic top as much as a pearl, and a sweet wrapper as much as gold leaf.’

When using hard materials like wood, linoleum or metal, Louise first drills holes for stitches and then uses simple running stitch, back stitch or anything that looks like sutures. She also uses a random weave stitch to work needle and thread over hard materials. The weaving technique was learned through a meander into basketry techniques, and Louise found it’s great for building up a surface and tethering down threads.

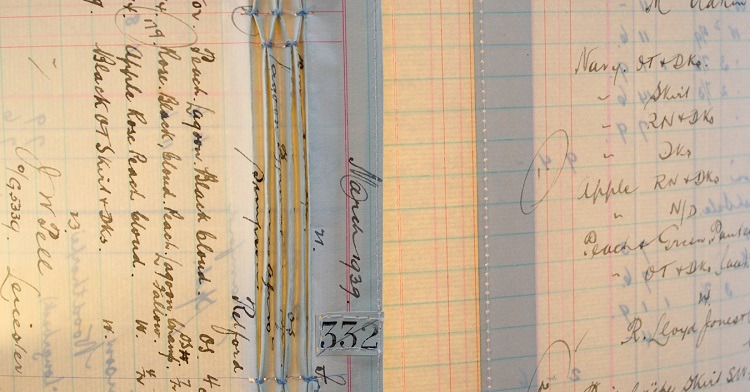

Temporary Condition is a series developed while Louise was building a new house next to her current one. When clearing and sorting out her studio, she found all sorts of ‘nonsense’ and decided to push it together into stitched assemblages.

Louise worked intuitively to create a record of the building process with its scaffolding, wiring, noises and tied down things. A thick wool felt was used as a contrasting material, creating a sense of insulation and calm. It was also functional and provided a blank canvas against the chaotic and worn materials discovered in the depths of her old studio. The materials are held together with staples, binding hand stitch and random weave stitch.

‘There was a lot of anxiety as we prepared to move, so I created the assemblages to describe the change that was occurring. The process of building on such a large scale as a house and making something on a more intimate and emotional level helped me capture some of my history and some of our future.’

Louise Baldwin is based in London, UK. She studied textiles at Goldsmith College London in the 1980s at degree and postgraduate level. Her work is held in public and private collections and has been shown in various exhibitions in the UK. Louise is a member of the 62 Group and Art Textiles: Made in Britain.

Instagram: @louisebaldwin_textiles

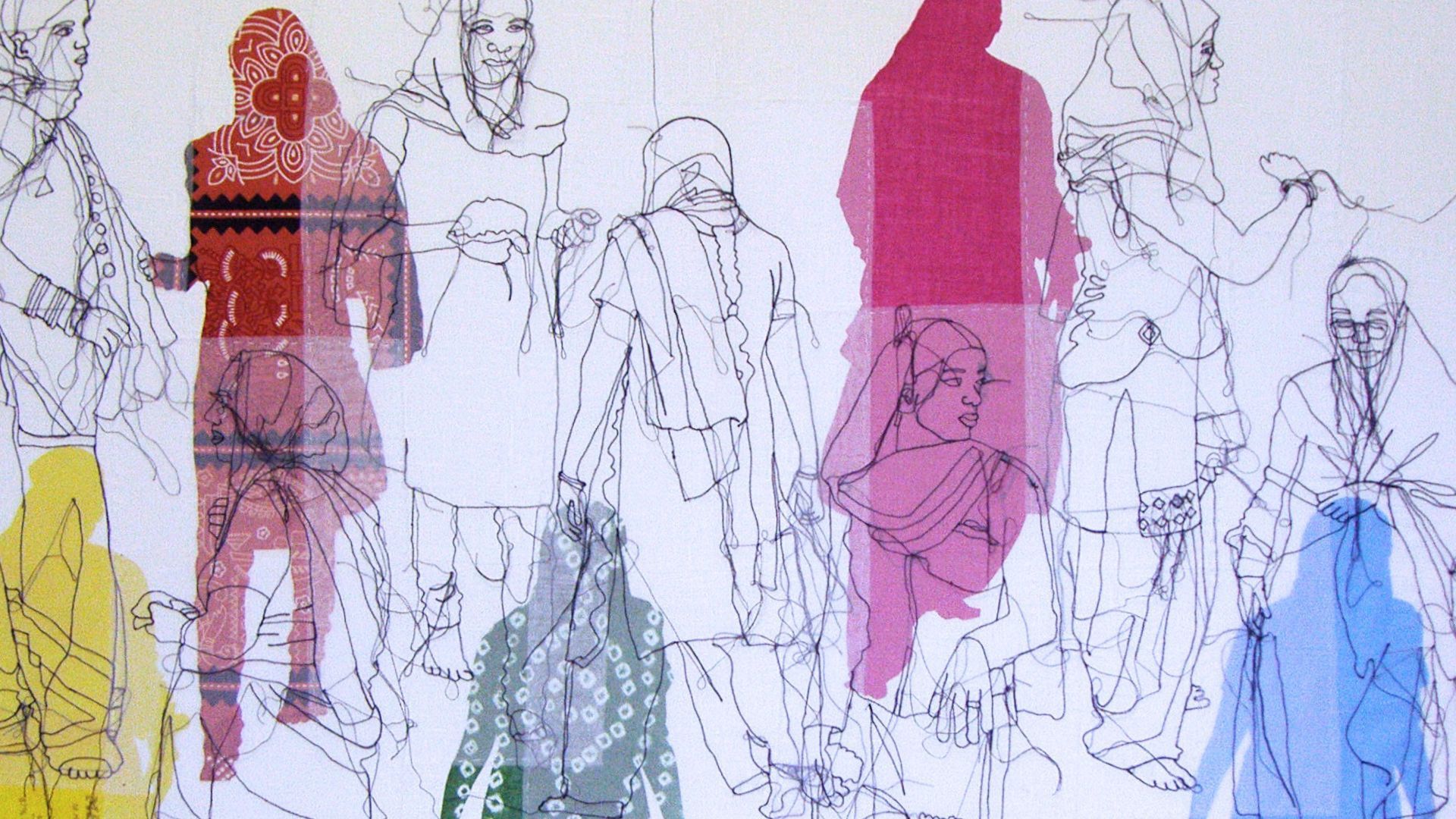

Zipporah Camille Thompson

There’s a special colour of blue found in the American Carolinas. It’s called ‘haint blue’ and it’s Zipporah Camille Thompson’s colour of choice. The rich indigo and cobalt blue connects to the coastal ancestral connections that inform her work, and this work is no exception.

‘This work was part of an exhibition that honoured and memorialised the life of my paternal grandmother, Allean, originally from South Carolina. She loved the colour blue, and she always reminded me of strong, gentle ocean waves in the way she greeted, encouraged and loved you endlessly. Her life was difficult, emerging gracefully from an abusive relationship and raising 11 children on her own. She worked fields, as well as working as a washerwoman, and she spectacularly cleaned everything from cotton to kitchen floors.’

Carolina Gold features a quilted hammock and altar that symbolise eternal rest, with printed silhouettes of sublime psychological and physical landscapes of labour and survival. The pots hold candles and other objects, and the prized rice of Carolina was included to pay tribute to Allean’s endurance, faith and compassion.

One can spend days looking at Zipporah’s collections of recycled works and see something new every time. And it’s remarkable how everything stays together! Drills, rope machines and sewing machines are among her chosen tools. But her favourite technique is weaving.

‘I love weaving! It allows me to continue finding the best kinds of junk and find connections between recycled materials and the woven cloth. It’s so satisfying finding ways to bring everything together through installation and sculpture. It challenges me to see found objects differently and in a new context, while using my creative problem-solving skills.’

Nothing is off limits for Zipporah, including chicken bones. She reports they are incredibly hard to clean and require bleaching and layers of painting. She’s also discovered no matter how much bones are cleaned and sealed, a greenish blue chemical oxidation happens over time. It’s a natural process she’s grown to love and embrace.

Zipporah’s sources for recycled materials are as unique as the items she finds. Of course, thrift stores are a given, but she reports there were plenty of times she scavenged along highways and ocean shores. Friends and family also provide gifts of old or neglected items.

‘For me, the more materials, the better. I’m all about high texture, bizarre surfaces and exquisite details. Roadside tarps, crystals, rocks, shells, fabric scraps, marine rope, hair weave, chicken bones, antlers and bedsheets are some of my favourites. It’s all about juxtaposition, and in my studio, my mantra is ‘everything is sacred, nothing is too precious’.’

Zipporah Camille Thompson is based in Atlanta, Georgia (US). Zipporah is represented by Whitespace Gallery (Georgia) and is an Assistant Professor of Textiles at Georgia State University. She is a recipient of many awards and residencies, including the Margie E. West Prize (2023).

Website: zipporahcamille.com

Instagram: @zipporahcamille

Melissa Emerson

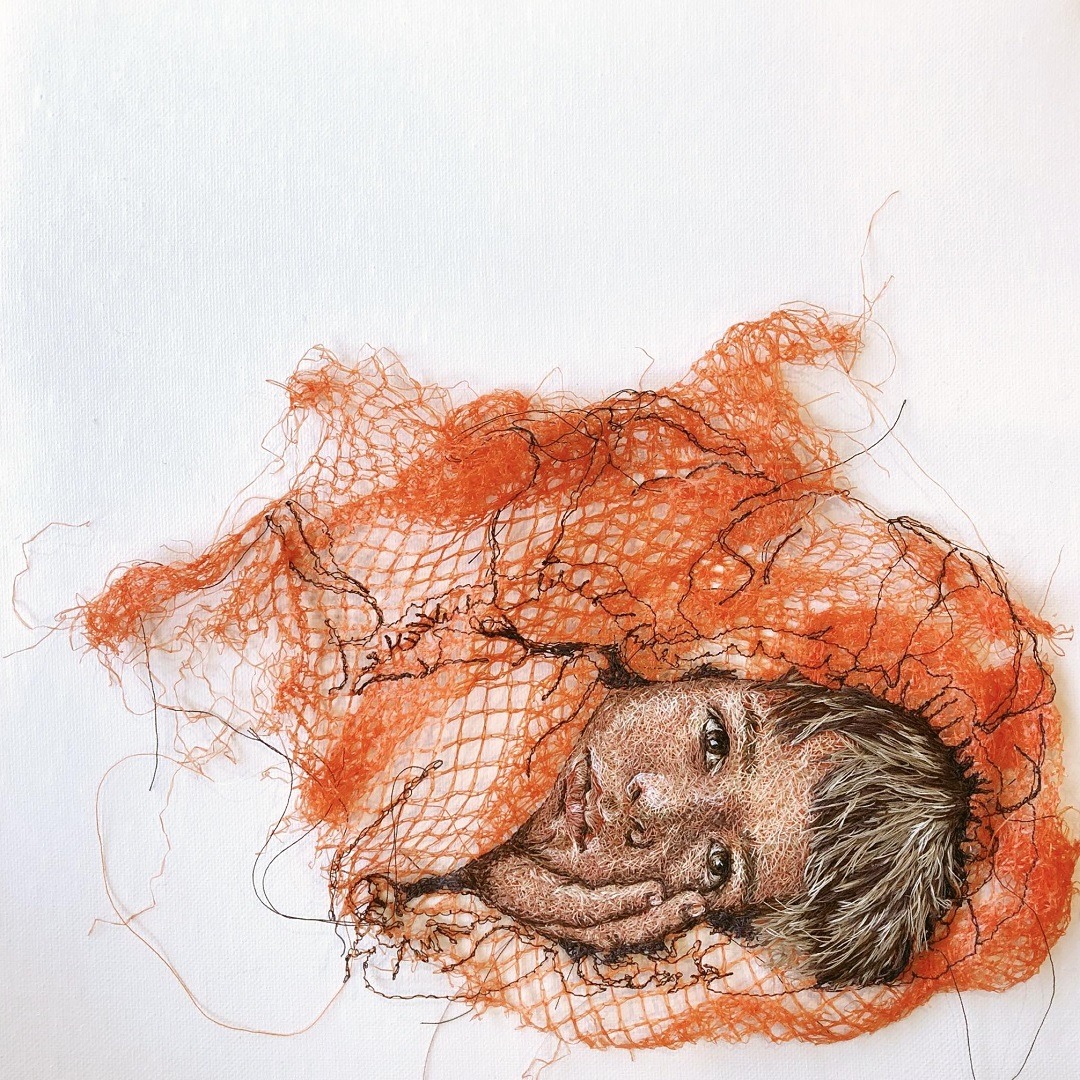

The fact Melissa Emerson’s tender scenes of a mother’s love are stitched onto plastic refuse tickles the brain in remarkable ways. Bubble wrap, bin bags, caution tape and, in this case, fruit netting, hardly seem loving and cuddly. But be assured, a fierce mama bear message is embedded in all of Melissa’s works.

‘I have an inherent need to document my motherhood experiences and feelings. In this piece, the netting is vibrant in colour and features strength and containment. It replicates my own protectiveness, strength and fragility as a mother. The netting can also be easily pulled apart and has areas of transparency, creating a further narrative exploring my vulnerability and fragility.’

Melissa especially enjoys working with found plastics in response to increased plastic waste problems across the globe. She also likes materials that can easily break to enhance her emphasis on vulnerability and fragility. She rarely starts a piece with a definitive meaning in mind, but instead lets the combination of her starting photograph and chosen material inform how the artwork develops.

Plastic materials also inform Melissa’s stitching techniques. Thinner plastics require very fine needles and slow and careful stitching. More transparent materials require overlapping stitchwork to keep them in place.

To stitch on such tricky surfaces, Melissa typically uses soluble fabric. Sometimes she’ll attach the soluble fabric to the plastic object, stitch and then wash away. Other times she stitches onto the soluble fabric separately, and once washed and dried, she’ll attach the stitched artwork to the object.

‘I really enjoy the unpredictability of working with recycled materials. There is always an element of risk, and I’m never certain how the finished piece will look or if it will even work as an artwork. In many ways, the act of making becomes more important than the outcome. Plus, I’m always looking for ways I can reduce landfill , including only using fabrics that are found or of significance to me.’

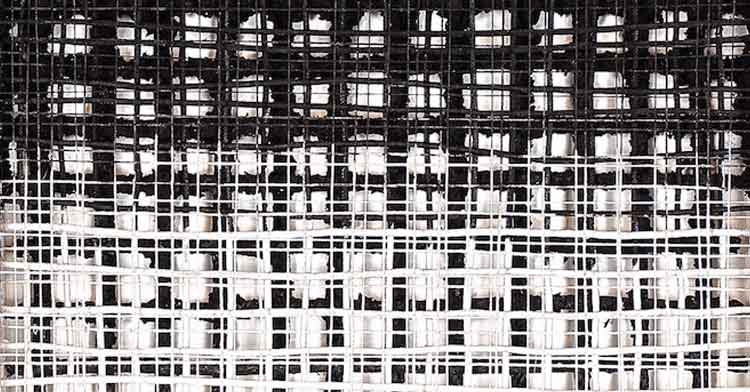

I Know Your Face started with a sketch from a photograph onto soluble fabric. Initially, Melissa worried the netting would fall apart after washing the soluble fabric, so she stitched in a very detailed fashion whilst creating many overlapping stitches to create a strong mesh surface. Before washing the soluble fabric, she pinned the artwork to cardboard to prevent the stitches from moving. There was still a bit of movement where the stitching was fairly sparse, but Melissa felt that only enhanced the piece.

‘This work represents the changes that occur over time and accepting I cannot hold on to key moments or control future events. My son and I look directly at each other, and our unspoken words acknowledge we are both present. A single glance demonstrates our shared understanding: I know him, and I get him. Cocooned in a sleeping bag, he’s comforted and secure in the strength of our connection. His innocence and trust in my strength and protection radiates.’

Melissa Emerson is a UK-based artist that recently returned to Northamptonshire, UK, after living in Canberra, Australia. She has exhibited in both the UK and Australia and has won several drawing category prizes for her textile work.

Instagram: @mel_emart

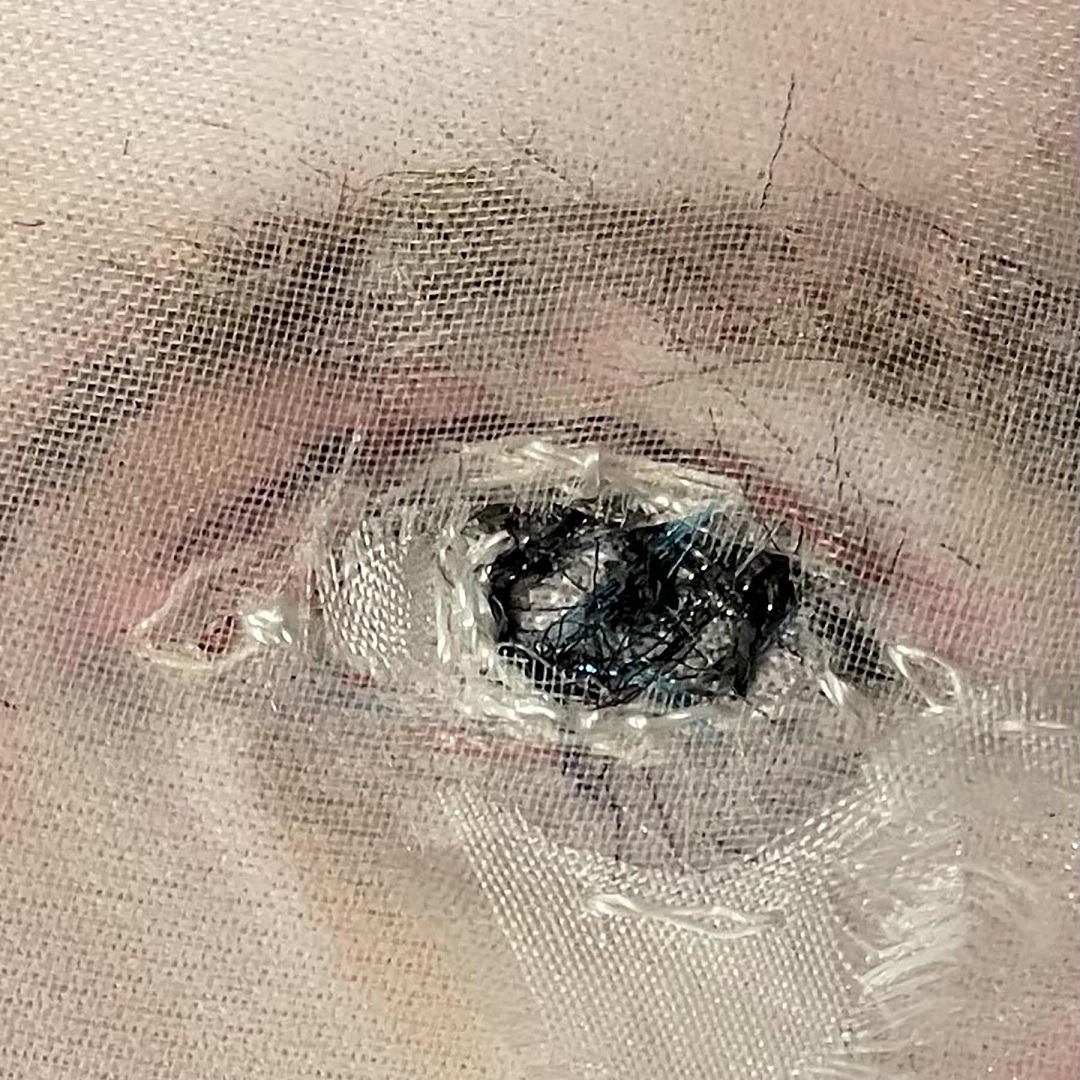

Stacey Chapman

Upcycling is how Stacey Chapman describes her process of building her fabric ‘palettes of paints’ from second hand materials. And she confesses her method has led to hoarding on a grand scale. She’s unable to stop turning something worthless into something of value, especially when the perfect material appears at the perfect moment.

‘I don’t think a psychology degree is needed to diagnose what’s going on. My practice is steered by my obsession of turning rubbish into works of art, as each work always starts with collating and touching materials before any making happens. The end result is like alchemy!’

For this work, that alchemy came to life when a long-time neighbour donated fabric to Stacey. The neighbour had never done so before, but the day she did was the same day Stacey was starting work on the coronation dress. It was the perfect fabric!

Stacey also shopped dead stock fabric stores when she realised her stash of tiny offcuts wouldn’t work for the large-scale figure. Those speciality stores sell leftover fabric rolls from high-end retailers and designers at discounted prices, giving the materials a second life and preventing them from heading to a landfill.

‘Every element of upcycled materials changes the overall look of an artwork. No one can recreate the fabrics or notions that have lived and seen many things before making their way onto my palette. Their back history becomes embedded into the quality of the art, and to me, that is unique and ever so special.’

1953 Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II is essentially a large, quilted jigsaw puzzle, as each element was created separately. Stacey used a wide variety of techniques, including hand stitch, appliqué and beading. Stacey also added her own hair, retrieving clean strands from the bath, coiling them into curls, and stitching each curl down with clear thread.

Stacey especially enjoyed creating the orb. Stitching the faux pearls and diamantes was a challenge, but Stacey was pleased with the layering of metallic gold fabrics and organza. The jewels came from costume jewellery she was gifted as a teen, and she was thrilled ‘they waited 30 years’ for a worthy project.

The sceptre’s long, thin shape proved to be a challenge as it bent easily, even after being created on mount board. So, Stacey used various shades of gold stitching to reinforce the sceptre’s gold rope, various shades of brown organza, and blue chunky glitter fabric.

Sadly, Queen Elizabeth II died before Stacey’s work was finished. Having lived in the UK all her life, the news led to an emotional rollercoaster. Stacey felt immense sadness but also huge gratitude to have had such an inspirational and unshakeable figurehead.

‘Her Late Majesty’s passing gave my project even more meaning and gravitas. It was very important to me that the finish be literally fit for a Queen. I wanted it to be sumptuous, rich and impressive. I also heard the Queen was fond of a remnant and a bargain, so I hope she would have approved of my thoughtful sourcing with sustainability in mind.’

Stacey Chapman is based in Margate, Kent, UK. She exhibits her work in galleries and accepts commissions, and she was awarded the largest artist sponsorship to date from Janome UK. Stacey is also a presenter and has been featured in many publications, including writing as a columnist for Love Sewing Magazine.

Artist website: artseacraftsea.com

Instagram: @art_sea_craft_sea

Facebook: facebook.com/ArtSeaCraftSea

2 comments

KEG Stocks

I relate to the themes that these artist have in common – using the unexpected and unplanned materials that find them in the circumstances of their lives. The invested meaning gives their work deeply touching value. Thank you for sharing.

Cynthia Millis

Some of these works feel “familiar.” The artists’ processes are very similar to mine. Much of my art is made with recycled items that come to my mailbox, or are found on walks, or are a recycle of previous art. Thank you for this wonderful post.