Textile artists who incorporate hand printing into their work know even their best laid plans can waver. Everything involved with printed surface design is up for grabs, including the physical pressure applied to a stamp or screen, room humidity, the type and strength of print materials, and base fabrics. Each printed pull or stamp is different from the rest.

We’re excited to introduce you to five artists who embrace and celebrate the inherent serendipity of printed surface design. While each artist has unique mark making techniques, they all agree the ‘anything can happen’ creative process is exciting. Every print is an experiment of sorts, and their hits and misses are equally gorgeous.

We start with Amarjeet Nandhra, who taps into her Indian heritage by using phulkaris to illustrate the devastation of displacement. Sue Hotchkis then showcases the impact of climate change through her printed and layered textile ‘fragments’. Bobbi Baugh explores the notion of ‘home’ across three heavily printed and stitched panels, followed by Leah Higgins, whose breakdown printing technique captures the ruins of the UK’s industrial mills. Finally, Ross Belton takes us to Africa and Japan through his traditional Ukhamba vessels.

Amarjeet Nandhra

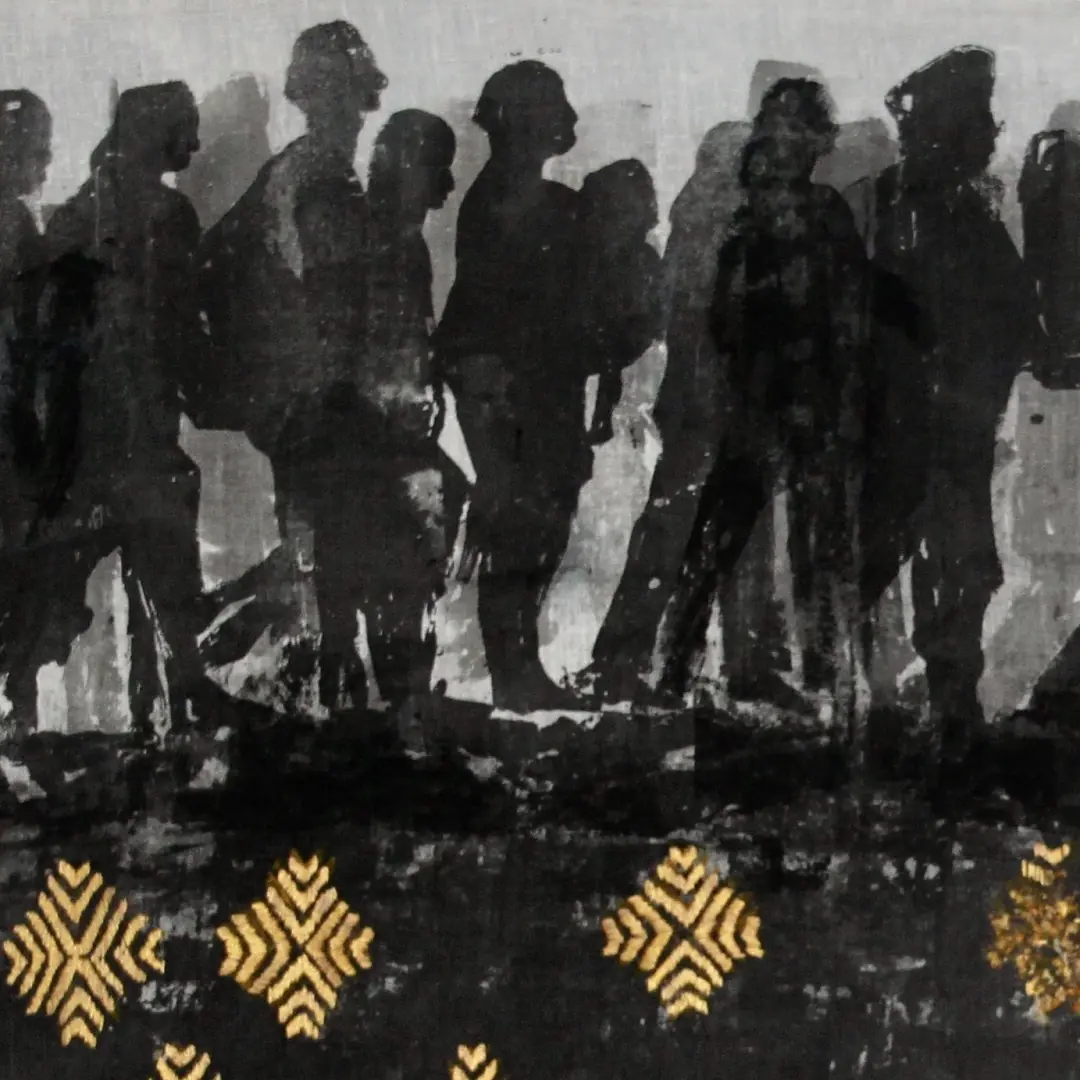

India’s 1947 partition caused one of history’s largest forced migrations. As Pakistan and India gained independence from Britain, a bloody upheaval displaced between 10 and 12 million people, including Amarjeet Nandhra’s ancestors. Communities were fractured, and many cultural arts were lost.

In light of that loss, Amarjeet wanted to reconnect to textiles from her Indian heritage, especially exploring the traditional patterns and symbols featured in phulkaris. These different styles of embroidered shawls originally from the Punjab region became her palette for sharing her own migration story.

‘My research revealed phulkaris have historically been viewed through a rather superficial lens. They’re often seen as simple colourful handicrafts or hobbies. That reductive view prevents a deeper understanding of the ways in which phulkaris mapped and documented the daily lives and social relationships of the makers.’

Amarjeet also discovered the earliest sample of phulkari dated in the 15th century was embroidered by the sister of the first guru of Sikhism. As a Sikh herself, that discovery further fueled her work.

Amarjeet’s creative process started with a rough draft showing how to build the layers of print. She then sampled ways to portray the layered figures using both a photographic and paper stencil. While the photographic stencil felt too clean and crisp, it allowed Amarjeet to experiment with different tonal values to create shadow figures. Ultimately, she hand painted directly on a screen using drawing fluid and screen block to create a softer, fractured quality.

Two layers of muslin were used in this work. The first layer features strong silhouettes, but it’s also somewhat transparent, creating a sense of something else going on in the background with the paler silhouettes showing through. After all the figures were printed in varying shades of grey and black, Amarjeet screen printed a traditional phulkari pattern in yellow using a hand cut freezer paper stencil. That layer also acted as her stitching guide.

‘I wanted the stitching to depict the fractious and destructive nature of forced migration. So, at the beginning of the piece, the repeating phulkari patterns are stitched in completely. However, the stitching unravels ever more across the rest of the piece to emphasise the damage and destruction of displacement.’

Amarjeet says print has always played a big part in her art since her first job at a print cooperative which produced banners for trade unions and many social causes. She was struck by the bold designs and repetition of images that could carry a message and communicate a story.

‘I love the physicality of printing, the smell of the inks and the sound of ink being spread out using a roller. Building up layers is the foundation of my practice. There is something magical about revealing the print and discovering the unexpected.’

Amarjeet Nandhra is based in northwest London, UK. In addition to being an artist, Amarjeet is also an educator at an independent textile school where she runs international teaching holidays and short courses. Amarjeet gained First Class Honours in creative art, and she is a member of The Textile Study Group.

Artist website: amarjeetnandhra.com

Facebook: facebook.com/amarjeetnandhra

Instagram: @amarjeetknandhra

Sue Hotchkis

The UK’s epic heatwave in 2022 led to fires, water shortages and thousands of deaths. Sue Hotchkis experienced it firsthand, and she described it as the planet’s way of screaming for help. The heatwave also intensified her existing anger at the government for its lack of concern for climate change, and both the heat and emotions collided to create Drought of Honesty.

‘The repercussions of climate change and concerns caused by humans’ destructive impact on the physical environment persist on a global level. Rising sea levels and increasing temperatures affect our everyday lives. Have we disconnected from the earth’s warnings? Are we being told the truth?’

This work started from a photograph Sue had taken at a rooftop café in New York. She had glanced over a wall meant to hide an air conditioning system and saw a pattern on the ground that looked as if something had been spilt or leaked. She grabbed her ever-ready camera and started taking close-up photos from all angles.

‘It looked like the cracked earth one sees from a drought. The substance had dried and cracked in the sun, and the pattern created an amazing image.’

It’s important to note that Sue’s artistic approach celebrates all things that are falling apart. She relishes decay in urban and rural environments, including peeling paint, rusted metal, cracked sidewalks, or a rotting log. She’ll take hundreds of pictures to capture the rich colours and textures that inform her ‘fragmented’ works of art.

For this work, Sue first used Photoshop to create images suitable for making thermofax screens (like a silk screen) for printing. She then hand dyed and printed on top of cotton fabric using Procion dye and discharge paste. Next, she created a design on her computerised sewing machine to stitch on top of the printed fabric. Strips of voile were then appliquéd using free-motion stitching. Other fabrics were then added and removed to form the overall shape. Finally, the printed and stitched fabric was laid over wadding and a backing fabric and quilted together. The right-hand side falls forward intentionally to create a 3D effect.

‘I’m inspired by erosion and decay. I aim to capture and convey the unconscious beauty of the way materials slowly break down over time by creating abstract fragments that hover between object and image. Shape and structure is integral to my practice, along with surface and texture.’

Sue says her work is also strongly influenced by the Japanese aesthetic of wabisabi that accepts transience and imperfection. It celebrates the effects of the passage of time, and this work in particular alludes to the rhythm and flow in nature using patterns formed by a drought.

Sue Hotchkis is based on the Black Isle in the Highlands of Scotland. She has participated in numerous group and solo exhibitions, most recently a solo show Alchemy at the Timeless Textiles Gallery, Australia (2019). She was the silver medal winner at the Scythia 12th International Biennial of Contemporary Textile Art, Ukraine (2018) and winner of Studio Art Quilt Association’s ‘Golden Hour’ fabric design competition (2017). Sue is also a member of Quilt Art.

Artist website: suehotchkis.com

Facebook: facebook.com/SueHotchkisTextiles

Instagram: @suehotchkis

Bobbi Baugh

They say home is where the heart is, and in Bobbi Baugh’s world, that heart is comprised of complex layers. The concept of ‘home’ has long been a favourite theme, and Bobbi’s earlier works depicted physical houses and a young girl on a journey. But this work captures the sense of movement in a home’s interior without creating a literal space.

‘I’m most interested in what is not immediately visible. And I am especially intrigued with seeing internal and external events in layers and depicting the two in composition together.’

This work’s external elements of a tree, gate, door and interwoven twigs are all photo transfers. Gel medium was used to transfer laser colour copies of original photos onto the fabric. To create the internal spaces, Bobbi used monoprinting and stitching to create patterned and textured window openings that invite the viewer to wonder ‘what’s in there?’. She also juxtaposed recognisable objects with ambiguous shapes and patterns to create a sense of dreaming.

Lastly, a path is suggested across all three panels to create a sense of journey. Birds on the first panel draw the viewer through the gate over to the door in the second panel. Viewers’ eyes then travel across the second panel through the window into the third panel, possibly landing in the bundle of intricate twigs. Birds serve as messengers and guides along the way.

‘Many ideas are sewn into this work. Home is a complex place where memories are intertwined with fragile lives. Leaving and finding home involves a journey. Dreams, memories and reality overlap. I hope viewers bring their own ideas and history to find meaning in the work.’

Bobbi says her 35-year commercial printing career cultivated an understanding of the rhythm of printing: ink the plate, create an image on that plate, press the fabric against it, pull the image, repeat. But ink is now replaced with acrylic paint, and plates are now made of gelatin or other low-tech relief techniques. Still, the results are striking, and it’s especially remarkable knowing this entire work started with white sheer polyesters and unbleached cotton muslin.

Printed fabrics are then gathered and stitching begins. Paint and collaged fabrics can be quite stiff, so Bobbi uses her sewing machines to stitch and quilt. Because they are small, narrow-throat portables, Bobbi stitches and quilts in sections, and then the sections are attached to the backing.

‘Construction of this work was an experiment for me, especially figuring out how to have multiple panels speak to each other. But I was invigorated by the ongoing energy of the composition as it emerged across the panels.’

Bobbi Baugh is based in Florida, US. She has extensively exhibited her work in group and solo shows across the US. She earned second place in the Nature Conservancy’s ‘Nature Inspires Art’ show in Kissimmee, Florida (2021) and first place in d’Art Center’s ‘Material II: National Exhibition of Fiber Artwork’ in Norfolk, VA (2020). She also wrote It was there I believed: a collection of visual artwork and poetry (2021).

Artist website: bobbibaughstudio.com/

Facebook: facebook.com/bobbibaughart

Instagram: @bobbibaughart

Leah Higgins

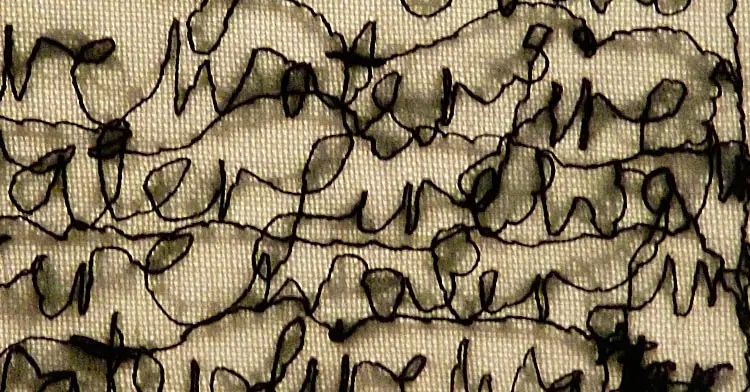

Leah Higgins admits she’s a control freak by nature, so creating random and abstract marks in her textile art was a challenge. She knew how to dye her own fabric, and she had learned several screen printing techniques. But it wasn’t until she discovered breakdown printing (also called deconstructed printing in the US) that she truly found her creative voice.

‘I experimented and experimented until I had a set of techniques that created the patterns and marks I wanted. The process was quite wasteful at first, but it ultimately helped me express so much more.’

Breakdown printing is a form of screen printing in which thickened dye acts as a form of temporary resist when applied directly to the back of a screen. The screen is left to dry before being pulled with either print paste or more thickened dye. The dried dye blocks the new dye or paste from passing through the mesh onto the fabric. As additional media is applied, the dried dye starts breaking down, resulting in unique marks and patterns for every pulled print.

‘I love the serendipity of breakdown printing and the fact I’m not 100 per cent in control. There is something wonderful about starting with a piece of white fabric and adding colour and mark.’

Ruins 9; Cottonopolis Revisited is part of an abstract series exploring what happens to unused buildings and industrial structures. In the 19th century, Manchester (UK) was nicknamed ‘Cottonopolis’ for its cotton industry which spanned 100-plus mills and nearly half a million employees. As the industry declined, mills were abandoned, demolished and repurposed. Still more were left to decay and erode, inspiring this work and others in her Ruins series.

Instead of using sketchbooks, Leah prefers to let ideas evolve and mature in her head. Because she works in series, she wants to be sure her subject is interesting enough to inspire multiple works. It can be a lengthy process, but once she starts creating a series, ideas flow quickly from one piece to the next.

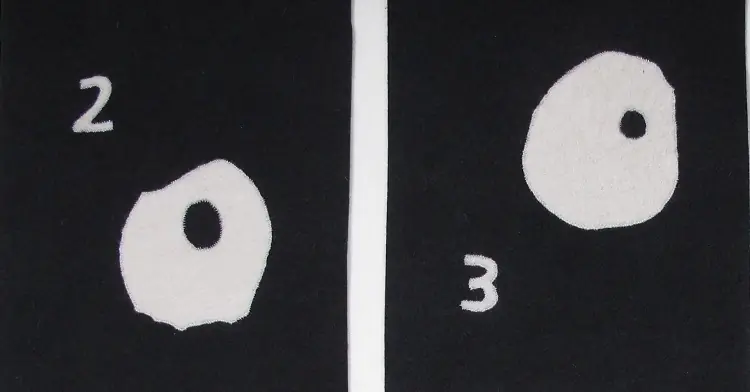

For this work, Leah first used breakdown printing to create a collection of fabrics in her preferred colour palette. She then cut the fabrics into ‘bricks’ that were randomly arranged and pieced onto felt. The first layer of stitch was added using a sewing machine that could handle the dense marks. Leah used appliqué and more stitch to add chimneys. Finally, the entire work was backed with hand-dyed cotton fabric.

‘Although printing is the most important part of my process, I am still a patchwork and quilter at heart. Quilting makes a significant difference in my work’s appearance, helping obscure the fact my art is made from many individual pieces. Stitch also allows me to add additional elements such as ghost-like buildings. For me, there is also a quiet joy in adding stitches.’

Leah Higgins is a textile artist, author and teacher based in Manchester, UK. Her art quilts have been exhibited widely in solo, group and curated exhibitions. She won the Art category at The Festival of Quilts twice and won Best in Show at Quilt=Art=Quilt in 2018. Leah also authored Breakdown Your Palette and Colour Your Palette.

Artist website: leahhiggins.co.uk

Facebook: facebook.com/LeahHigginsArtist

Instagram: @leahhigginsartist

Ross Belton

Ross Belton spent many childhood holidays along Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal coast. When not at the beach, his family explored rural areas and many roadside markets. Ross marvelled at the residents’ ingenious use of found materials to create art, and now that same repurposing informs his own textile art.

‘The craftspeople worked with whatever they had to hand. They recycled everything from tin cans, bottle tops, cable wire and cloth fibres. I always coveted their wire cars with wheels made from shoe polish tin lids. My textile art similarly explores and embraces the flaws and hidden beauty often missed in everyday things.’

As an adult, Ross collected traditional African fabrics, including mud cloth and woven raffia Kuba cloths. Then after seeing a Japanese boro exhibition, Ross was again blown away by boro’s purposeful use of recycled materials. He took an indigo/shibori workshop run in conjunction with the exhibition and was hooked. His work now blends African and Japanese traditions with print and dye in a sustainable fashion.

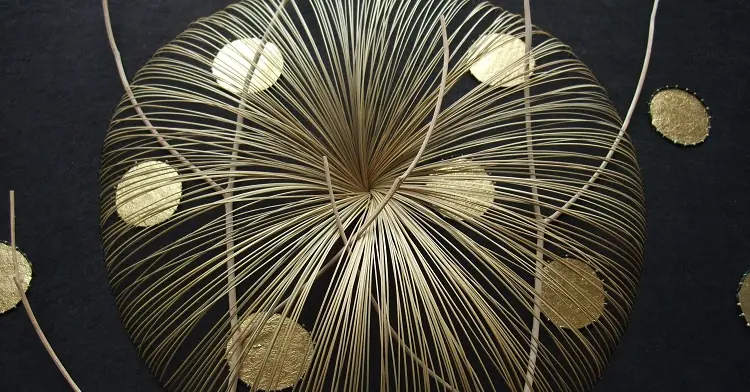

This work is one of several ‘Ukhamba’ bowls Ross has created that mimic traditional Zulu rimless clay beer pots. The pots were used in ceremonial drinking of beer to remember and appease ancestors. The pot would traditionally be passed among males from the eldest to the youngest.

Ross especially sought to explore the ‘tannin iron complex’ in dyeing his bowls by using only natural coloured dyes that are modified by iron (rust). For this bowl, gauze was wrapped around blacksmithing tools, and then the bundles were left outside to be naturally wetted by rain, creating unpredictable rust marks reminiscent of the clay beer pots. Once the rust process was complete, Ross dyed the bundles with logwood, knowing the dye would darken the cloth and further enhance the rusted metal marks. He describes the end result as ‘textile alchemy’.

‘My biggest challenge was getting the fabric to hold its shape. I used plaster of Paris in my early experiments, but it dried very hard and made stitching difficult. After much experimentation, I now use a combination of PVA glue and starch which varies depending upon the size of the bowl.’

Boro stitching is then used to keep the fabric in place for the dyeing process, as well as to embellish the bowl. Linen thread is used for foundation stitching due to its strength and ability to absorb dye which helps it blend into the background. White cotton crochet and sashiko threads are then used for decorative stitchwork.

‘Much like the vintage metal tools I collect, I use secondhand or vintage threads. In our throwaway society, youngsters tend to toss “old junk” when clearing a relative’s home. So, I often buy old sewing baskets that house an endless variety of useful tools and threads.’

Ross Belton is based in London, UK. He has exhibited his work extensively in Europe, most recently at the Lloyd’s Register Foundation ‘Safer World Conference 2022’ and the Embassy of Japan, Piccadilly London (2020). Russ also established a Nomadic Dye Garden and offered outdoor community activities at St. Saviours (London) in association with the Florence Trust (2020-21).

Artist website: moderneccentrics.wordpress.com

Facebook: facebook.com/people/Ross-Belton

Instagram: @spottedhyenas

Comments