Textile artists have long forged their own way, but they can be especially rebellious when it comes to three-dimensional art.

In addition to amazing aesthetics, textile sculptures also feature a remarkable nod to engineering.

Very few traditional sculpting materials can compare to textiles’ unique combination of strength and lightness. Woven fabrics can be remarkably durable, yet also float upon the slightest breeze.

Even a single thread weighing less than a butterfly’s wing can bring muscle to a sculpture. And textiles can be manipulated in incredible ways through folding, pleating, tearing and more.

Yet, along with all the positives, there’s a challenge: figuring out how to help fabrics maintain their intricate shapes and forms. But that’s where 3D textile art gets even more exciting, as sculptors come up with ingenious ways to help fabrics hold themselves upright in their manipulated splendour.

Meet five textile sculptors whose works will both surprise and delight. Amanda McCavour fills a huge exhibit space with thousands of blue objects made entirely from thread, and Leisa Rich introduces us to her luxurious vinyl river monster. Bryony Jennings’ incredible wolf sculpture is made from vintage fabrics, while Benjamin Shine uses tulle to capture the intricacies of his grandmother’s hands. Kinga Foldi concludes our 3D journey with an exquisite silk mushroom.

Amanda McCavour

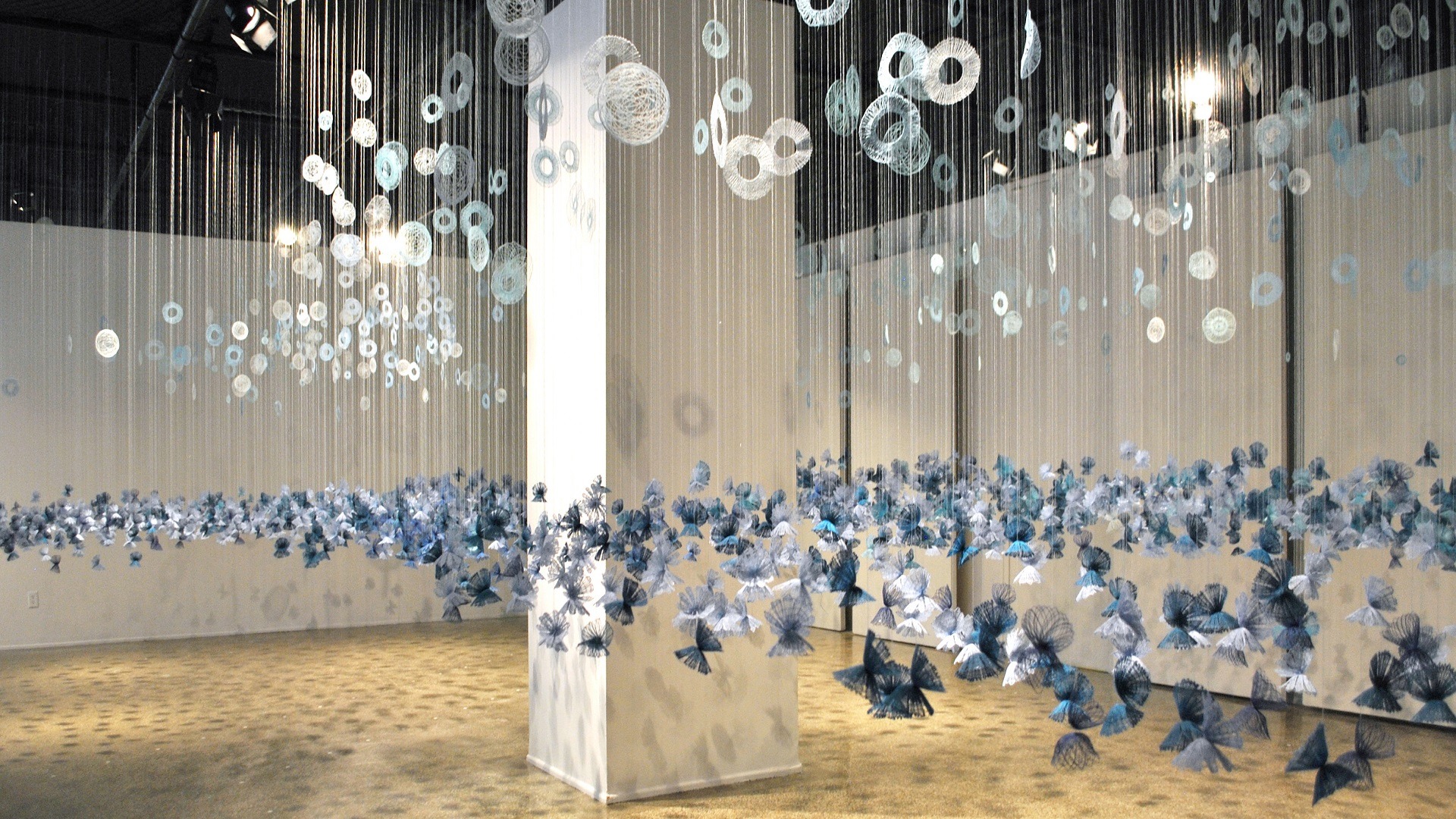

Amanda McCavour’s textile installations feature a wonderful mix of art and engineering. She is fearless in imagining how to fill very large spaces with her work, yet it’s remarkable how the end results retain a sense of intimacy and wonder.

Far Away Blue Fields features over 2,500 separate pieces positioned along walking pathways that immerse viewers in the art. Fifteen people helped attach strings to each piece, and then Amanda and an assistant climbed up and down ladders to tie each thread to a ceiling grid. It took a week to install the entire artwork.

Amanda McCavour: ‘I see the installation as part of the making process. We mapped accessible pathways on the floor, and then I established a high and low point for the embroideries. But it’s challenging to see depth from atop a ladder, so when I’d step down, many additional adjustments were needed.

‘This work represents an imagined blue world where the sky touches the earth at the horizon line. It was inspired by Rebecca Solnit’s book A Field Guide to Getting Lost in which the author describes ‘the blue of land that seems to be dissolving into the sky’.

First Amanda adapted previous works and tested different shapes using radial stitch patterns. She tested scale and movement by hanging pieces from her studio ceiling. Then she shared sketches and photos of her tests with the Centre MATERIA gallery in Quebec City, where the work would be exhibited. After much discussion, she returned to her studio to start fabricating the embroideries.

She created lacy structures with free-motion embroidery on water-soluble stabiliser. The crossing threads create strength, so when the fabric is dissolved in water, only the thread structures remain. Once the pieces dried, Amanda used a hair straightening flat iron and manual tension to mould the shapes into 3D forms.

“The fabric dissolving process is both a challenge and delight with an element of chance.”

Amanda McCavour, Textile artist

Amanda: ‘Sometimes unexpected things happen as the threads move and wiggle around. The work always shifts and changes as the base layer is slowly removed. I like that because there’s a part of my making personality that can be quite controlling. It helps me let go and see its magic!’

‘I see this piece as an abstracted landscape, but I also like how the forms could reference florals, butterflies, jellyfish or simply abstract forms. I also think the work has a breath. It contracts and fits in a small space, and then when it is installed, it breathes out to expand and fill the space.’

A love of drawing and exploration of ‘line’ in its simplest sense led Amanda to consider working with thread. She loves thread’s fine nature and how, while it appears to be flat, it’s actually a sculptural line. She also enjoys how the transparent pieces move with even the slightest air currents in a room.

Amanda McCavour is based in Toronto, Canada. Her site specific works include art at The Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, WI, USA, at Centre MATERIA, Quebec City, Canada, and at the Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina, USA.

Artist website: amandamccavour.com

Facebook: facebook.com/amandamccavourart/

Instagram: @amandamccavour

Leisa Rich

When Leisa Rich visited the Disney theme park in 1965, she was five years old and newly able to hear from one ear. Leisa had been deaf since birth, so being able to both see and hear the attractions was beyond amazing.

She was especially moved by the It’s a Small World ride and says she has never lost her delight in discovering its bright exotic characters and ‘tinny music’.

Leisa Rich: ‘I think I became an artist because my deafness heightened all my other senses, and I still see the world in that fantasy fashion. I live my life like an adult-child existing in a perpetually fantastic, albeit crazy and depressing, world. I think that’s also why I don’t experience creative block.’

“I see wonder in everything, even in silverware tongs or the wrinkles on my skin.”

Leisa Rich, Textile artist

Great Saint Lawrence came to life when Leisa moved back to her birth country of Canada where she bought a 96-year-old farmhouse along the Saint Lawrence River in Ontario. She was amazed by the river’s ever-changing, mercurial elements that flashed silver in ways that looked like large moving shapeshifters. One day it seemed as if a monster emerged from the reflective surface and begged Leisa to recreate him.

Leisa used metallic vinyl to create the individual hanging pieces, and then she stuffed each with traditional batting. But before sewing everything together on her beloved vintage Bernina 807, she grabbed a very sharp pair of dressmaker shears and sliced into the vinyl. She had planned to create a feathery feeling, and was delighted to discover the slits made the pieces swirl and curl as viewers walked by the sculpture.

During the making process, she is always thinking about the experience people have when seeing her work. She wants her art to offer both a visual and tactile interactive experience.

Vinyl has long been one of Leisa’s favourite materials. Its rigidity and softness allow her to create works that hold their shape. The edges don’t fray and there are so many surface design options. But vinyl can be tricky, especially when it sticks to itself.

Leisa: ‘Even after many years of sewing, I still find myself fighting with the vinyl at times. I use free-motion machine embroidery to give me better control. Sometimes, I’ll use tear-away fabric on the plastic side to help the machine grip the vinyl. This is especially helpful for the complex twists and curves I feature in my work.’

Leisa Rich is based in Howe Island, Ontario, Canada. Her works are featured in permanent collections including the Dallas Museum of Art (US), Delta Airlines, Inc., and the Kamm Foundation. Leisa holds a Master of Fine Arts (University of North Texas, US), a Bachelor of Fine Arts (University of Michigan, US), and a Bachelor of Education in Art (University of Western Ontario, Canada).

Artist website: monaleisa.com

Facebook: facebook.com/Leisa-Rich-Visual-Artist-and-Art-Educator

Instagram: @monaleisa2

Bryony Jennings

Bryony Jennings’ signature textile menagerie is filled with a variety of ‘beasties’ whose charms are irresistible. From mice to owls to rabbits and foxes, each of her figures has something to say with a wink and a nod.

Bryony Jennings: ‘My storylands are a cathartic means to communicate my thoughts and feelings to the world. Animals carry their own burden of human symbolism that I combine with my own ideas to suggest character and, perhaps, a little soul. My stories are non-prescriptive, and I hope viewers receive and interpret a meaning that transcends the physical object alone.’

Bryony’s purposeful use of reclaimed textiles to create her creatures adds to their appeal. She enjoys knowing the fabrics she uses bear imprints of lives previously encountered, infusing a sense of history into each animal. Most of her materials have been handed down, bought in thrift shops or kindly donated.

Bryony: ‘Car boot sales were a weekly highlight of my childhood so, by nature, I’m a gatherer and collector of the worn out, unloved and discarded. I find beauty in the detritus of the everyday, including old clothes, household linens and timeworn draperies carrying the marks of time and discarded memories.’

Ulfred started from a gifted gunmetal-grey beaded table runner that spoke ‘wolf’ to Bryony. She created a skeleton by intuitively bending and twisting wire to form a solid base. From there she added flesh by wrapping the armature with reclaimed fabric scraps, securing them with stitch, filling the void with stuffing to create a very solid undressed body shape.

“Balancing a wolf on his back and trying to stitch in between his claws is trickier than one might think – every creature I make teaches me something new.”

Bryony Jennings, Textile sculptor

Bryony brought Ulfred’s form to life by adding his facial features and more layers of fabric to bring a variety of colours and textures to his coat. Bryony uses an array of upholstery and darning needles, along with upholstery threads, for sculpting and construction. Visible and functional stitching is completed using six-stranded embroidery cottons.

For this work, Bryony chose the name Ulfred, which means ‘wolf of peace’ in old English, to suggest he carried no malice.

Bryony leads a variety of 3D sculptural workshops. Her students’ greatest challenge when using textiles is often letting go of the ‘rules’ associated with textile work, especially for the more experienced stitchers. She stresses to her students that you can’t be too precious with materials when working with sculpture. Experimentation and taking chances are the only ways to learn and succeed.

Bryony Jennings is based in Portsmouth, UK, where she works as both an artist and international educator. She was featured on the cover of Embroidery magazine (Sept/Oct 2022). Her solo exhibition at the Bodleian Library Shops (Oxford, UK), in 2022, featured eight giant library mice.

Artist website: prettyscruffy.com

Facebook: facebook.com/BryonyRoseTextileMenagerie

Instagram: @bryonyrosejennings

Benjamin Shine

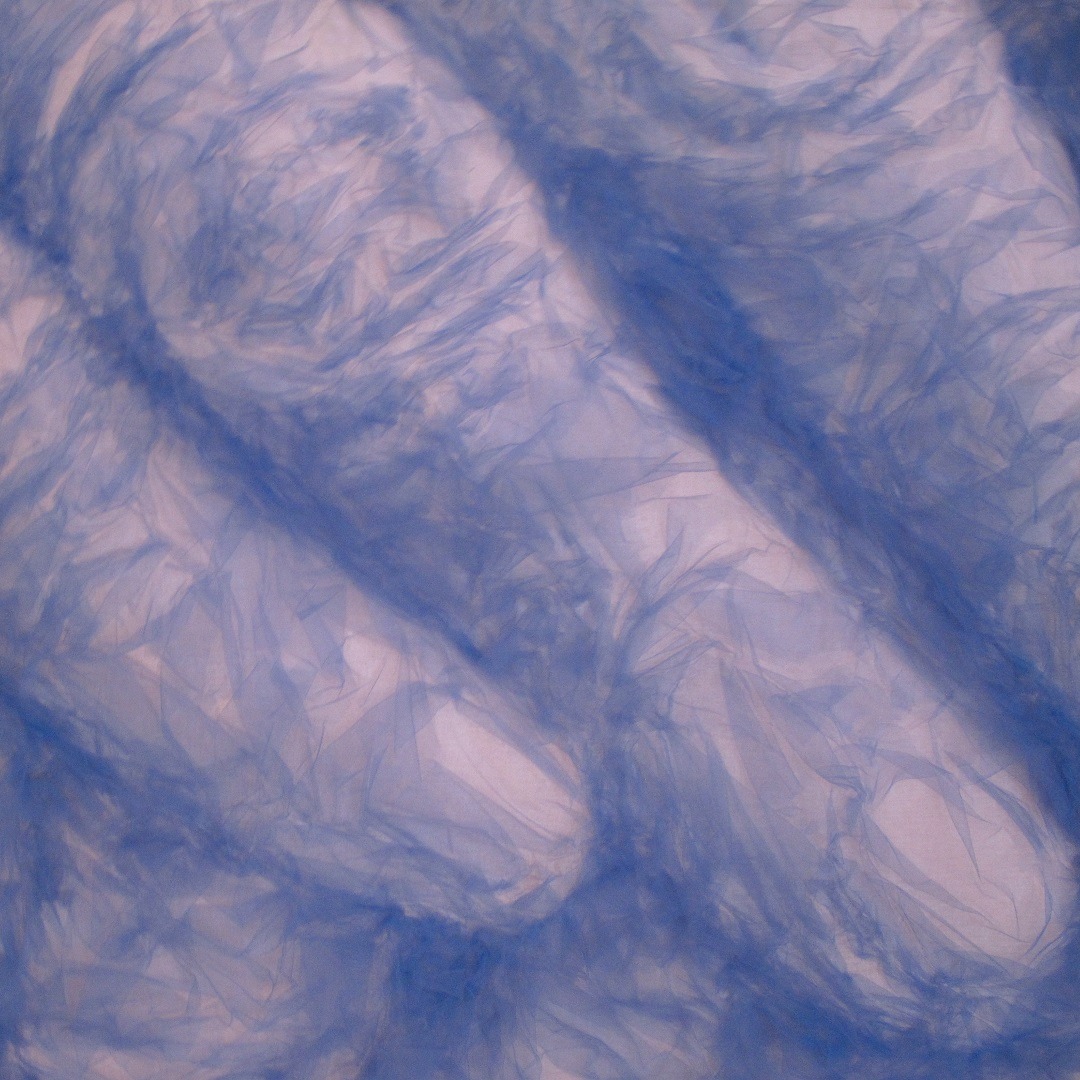

The word ‘ethereal’ takes on a whole new meaning when viewing Benjamin Shine’s floating tulle sculptures. Tulle is known for its fragile and transparent look, but its overall nature can also create remarkably distinct lines and complex shading when twisted, folded and otherwise manipulated.

Benjamin Shine: ‘I want my work to look like smoke, and I think tulle lends itself to ideas of smoke’s impermanence. Its inherent translucency can suggest a surreal, inky effect, as if energy momentarily forms into something recognisable before dissipating into nothing.’

“There are two stories told in my art: what I make happen and what the tulle makes happen.”

Benjamin Shine, Textile artist

His creative process is as ethereal as his art. Benjamin intuitively directs long swaths of tulle against a canvas and then uses a basic clothes iron to fuse various folds, bends and twists. The dry iron heat warms the tulle in a way that when it cools, it becomes more rigid and sets the shape of the fold or scrunch, which further helps everything else stay fixed in place as a sculpture.

And Benjamin certainly has war stories of lifting an iron away from an area worked on for hours, only to find a big hole! But practice has lessened those instances, along with his habit of triple checking the iron’s setting is on ‘synthetic.’

Benjamin: ‘Prior to creating Remembrance, I had been trying to see how accurate and detailed I could be. But this work exposed an in-between approach in which I allowed the natural flow of the fabric to be more present. I guided the tulle more than forced it to capture its inherent materiality and energy.’

Remembrance was initially designed for the now-closed SCIN Gallery (London, UK). While out walking one day, a large artwork in SCIN’s window caught Benjamin’s eye. Upon entering the building, Benjamin discovered the upstairs gallery showcased interesting textiles, artworks, and objects inspired by a ‘materials library’ for architects and interior designers housed in the building’s basement.

Benjamin wanted to be a part of the gallery’s creative use of materials, and the gallery owner was excited about Benjamin’s work as well. Inspired by the gallery’s name, Benjamin sought to create a work emphasising texture, hands and touch. He researched a variety of hand poses that evoked a sense of gentleness, calm and contemplation. But he ultimately chose an image of his grandmother’s hands to conjure a sense of thought and remembrance.

Benjamin: ‘It was created as an installation, so I didn’t have to worry about framing the work behind glass. I wanted the tulle to be exposed so viewers could enjoy the surface textures on a large scale. I enjoy viewers’ surprise when they ultimately realise the work is made from tulle. I’d rather my sculptures not be read as fabric first, but as something else more interesting and unusual.’

Benjamin Shine is based in Australia. After studying fashion design at Central Saint Martins, UK, he set up a studio to design innovative apparel, products, furniture, mixed media works and sculptures. Benjamin exhibited at the Boccara Gallery, LA Art Show, Los Angeles, USA, 2019, and at Barclays, Monaco, 2019.

Artist website: benjaminshine.com

Instagram: @benjaminshinestudio

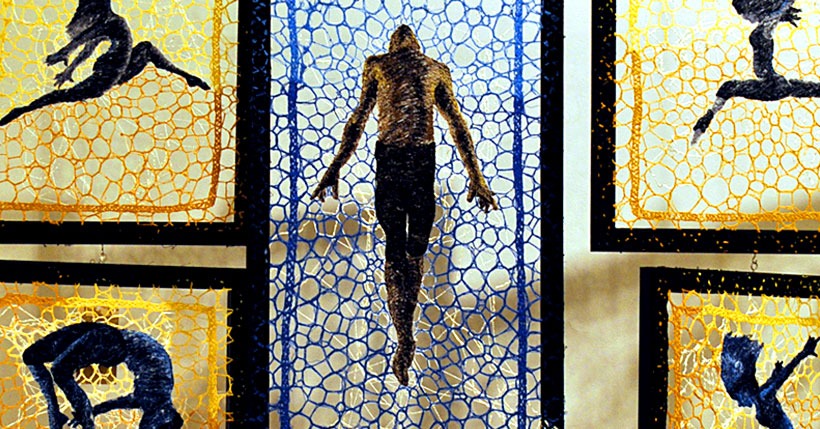

Kinga Foldi

When Kinga Foldi graduated in 2006 with a degree in woven textile design, the last thing she wanted to do was work as a designer. She had always preferred making crafts, especially those with dimension, so she became a sculptural costume designer for theatres and choreographers.

Kinga Foldi: ‘The university years were important for learning the diversity of textile art. But even when I enjoyed making costumes, something was always missing. I couldn’t express my thoughts and feelings, and I didn’t have the courage to set aside functionality to solely concentrate on shape.

‘Finally, after years of experimentation, I felt confident enough to create free-standing sculptures. And not surprisingly, many of the shapes I use come from my costume work.’

Kinga’s signature artistic elements are her use of silk and the pin tuck technique. Often used to decorate blouses, pin tucking features repeatedly pleated fabric to create a rhythmic striped surface. Like an accordion box, the pleats can bend, expand and stretch depending on the tension that connects them and the direction in which they are pulled.

“Often, the silk shows me something I wouldn’t have done, but the moment I see it, I know that is how it should be.”

Kinga Foldi, Textile artist

After creating a simple sketch, Kinga chooses white or very pale cream-coloured silks. She prefers a neutral palette to allow the intricate folds and shapes to take centre stage.

Kinga covers the silk with a cornstarch mixture that produces a rigid paper-like quality when dry. She then creates hundreds of pintucks, all of which are then hand stitched together at various points. By pulling or relaxing the connecting threads, her shapes morph and twist. Once the elements start flowing together, Kinga applies a special textile glue that makes the silk softer and easier to bend. When the glue dries, the folded forms stand solid.

Kinga: ‘The pleated silk always shows me the way. I am impressed with how the pintucked surface ripples and its combination of softness and movement.

I enjoy our ‘conversation’ and want to preserve both the silk’s dynamism and fabric-like qualities.

Kinga says she ‘met’ real silk while attending Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (Budapest, Hungary). She was struck by silk’s unique shine and its slight sticky touch. Her favourite silks to work with are dupioni or shantung, as both are crisp and feature prominent slubs. But because silk isn’t cheap, it’s always a challenge to keep mistakes to a minimum so as not to waste the precious material.

Kinga: ‘In addition to silk’s qualities, I appreciate its diverse cultural and spiritual traditions. Silk has long been considered a symbol of wealth, but the silkworm and cocoon itself are also symbols of the soul on a spiritual path. Silk has also been viewed as a link between our world and the transcendental, and it’s well known for its healing powers. It’s a miraculous treasure.’

Kinga Foldi is based in Budapest, Hungary. Her works are largely informed by nature, and she strives to create ‘soul-resting’ objects that allow the luxury of slow observation in an overstimulating world.

Artist website: baharat.hu

Facebook: facebook.com/kinga.foldi

Instagram: @kingafoldi

1 comment

Anita Gercāne

Benjamin Shine, “Grandma’s Hands” is so amazingly delicate and emotional!